Bryan Ellicott said he was “humiliated and embarrassed' by being asked to leave a men's locker room at a city pool last summer.

A 24-year-old Manhattan transgender man is filing suit against the Parks Department and the city for being denied access to locker room facilities at a public pool in Staten Island that he and friends had used regularly since they were youths.

Bryan John Ellicott alleges that on July 21 of last year, three staff members at the Joseph H. Lyons Pool, a Parks Department facility, ordered him to leave the men’s locker room as he was changing his T-shirt prior to using the pool. He was originally approached, he said, by one pool staffer, who explained he had received a complaint from someone who said he shouldn’t be there. When Ellicott asked to speak to a supervisor, two other staff members backed up the first one, telling him he needed to either use the women’s locker room or leave.

“I was humiliated and embarrassed for being singled out,” Ellicott told reporters outside the New York County Supreme Court building in Foley Square on June 3. “It was sad and hurtful.”

According to the complaint filed on his behalf by the Transgender Legal Defense & Education Fund (TDLEF) and pro bono attorneys from Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton, the third pool employee, the most senior of the three, “appeared uninterested in the matter,” telling him “something to the effect of, ‘If you don’t like it, you can leave.’” Ellicott said the staff members cited no specific law, regulation, or policy in ordering him to leave the locker room.

He said he has not used public pools in the city since the incident out of fear of facing further humiliation.

The lawsuit cites the 2002 amendment to city human rights law that bars discrimination based on gender identity and expression, alleging that the pool staff members acted in a discriminatory fashion in denying Ellicott access to a public accommodation.

Transgender Legal Defense & Education Fund seeks clear court ruling that 2002 transgender rights law affords unimpeded access to single-sex facilities

“We are asking the court to send a clear message,” said Michael Silverman, TLDEF’s executive director. “Transgender people need to be treated equally. They can’t be treated differently, as second-class citizens.”

The suit cites a variety of policies, in New York City agencies and according to federal government guidelines for its agencies, that afford transgender people access to single-sex facilities, including locker rooms and bathrooms, according to their affirmed gender. In “Guidelines Regarding Gender Identity Discrimination” issued by the city Human Rights Commission in 2006, the denial of such facilities to transgender people “suggest[s] that discriminatory conduct… has occurred.”

Silverman explained that despite the 2002 nondiscrimination law, a 2005 appellate ruling in New York found that denying bathroom access to a transgender person was not discrimination because the individual was free, like anyone else, to use a facility corresponding to their gender identity at birth.

“For transgender people, of course, that is meaningless,” Silverman said. “That ruling was wrong when it was decided, and it is wrong today.”

The 2005 ruling came in connection with events that took place in 2000, two years before the city enacted its transgender civil rights protections.

TLDEF, however, is looking to establish a clear precedent that denying transgender New Yorkers access to single-sex facilities appropriate to their affirmed gender is discrimination under city law.

The State of New York has no specific civil rights protections for transgender people, nor does the federal government, though two years ago the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, in a case brought by a transgender woman denied employment at a federal agency, embraced the view that discrimination based on gender identity is sex discrimination, outlawed by the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

According to Silverman, prior to filing his lawsuit, Ellicott lodged a complaint with the city Human Rights Commission, which, despite its 2006 “Guidelines,” took the position that it lacks jurisdiction in this matter. Asked to clarify why it does not have jurisdiction over an area on which it established guidelines, the Commission, through a spokesperson, referred the question to the City Law Department.

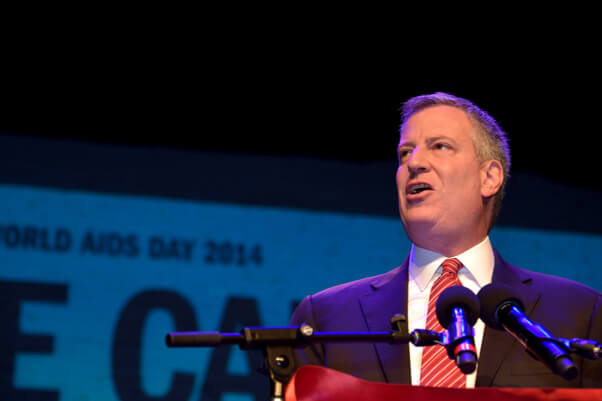

The Parks Department did not return a call seeking clarification about whether the treatment of Ellicott is official policy, and the mayor’s office did not respond to a request for Mayor Bill de Blasio’s view of how transgender individuals should be accommodated in city facilities. As a City Council member in 2002, de Blasio voted for the transgender civil rights law, and during his career he has typically been an LGBT community ally.

In an email message, a spokesperson for the City Law Department, which defends the city in such litigation, wrote, “We will review the lawsuit when we are served.”

In speaking with reporters, Silverman emphasized that what Ellicott experienced “happens all around the country every day.”

Ellicott explained the precautions he routinely takes to avoid the type of problems he described in the Staten Island pool. When out with friends, he said, he often visits a restroom with a “buddy” to make sure he is safe. In 2012, he was assaulted in a public bathroom in Union Square and required medical attention at Beth Israel Hospital. When he is out on his own, Ellicott said, he typically tries to keep track of nearby venues like Starbucks that have gender-neutral private bathrooms.