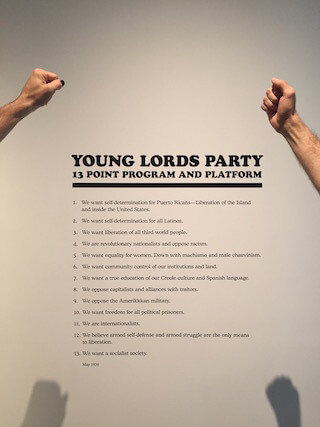

The Young Lords Party’s “13 Point Program and Platform,” as displayed at the Bronx Museum of the Arts and photographed by Camilo, a 20-something man who came to New York from Colombia.

For five years, Johanna Fernandez, history professor at Baruch College, worked to set up three separate art installations around New York City, one of which she curated. She worked, without funding, to tell the story of the Young Lords, a 1960s, mostly Puerto Rican street gang that morphed into a revolutionary action group inspired by the Black Panther Party.

Late this July, “¡Presente! The Young Lords in New York,” opened at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, at El Museo del Barrio in East Harlem, and at Loisaida Inc. on the Lower East Side.

I have a hard time with political nostalgia; it can come off as romanticized rhetoric and transform a worthy and dimensional cause into a cartoon. But there’s nothing flat or cartoonish about the exhibit at the Bronx Museum. Curated by Fernandez with Yasmin Ramirez, this wing of the three-site show is an elegant explosion of radical history. It’s also a deeply felt dedication to Puerto Ricans who, leaving US-induced poverty on the island, came to this city looking for a better life, only to become New York’s next source of cheap labor.

Snide Lines

True crime pundits are all over “the militant ‘60s.” Maybe you’ve heard about the infamous 1970 Young Lords takeover of Lincoln Hospital from the “thugs-’n-drugs” perspective of the mainstream media? Go, then, to this exhibit to see that takeover through the eyes of people who desperately needed better working conditions and medical care. Go to all three exhibits to understand the effort and heart it took to keep the Palante newspaper going, to watch footage of Young Lords — kids, mostly — occupying an East Harlem church, setting up free food programs, free clinics, giving poetry readings, teaching history lessons. Read the Young Lords Party’s “13 Point Program and Platform,” that included self-determination for all Latinos, community control, the full equality of women.

Two generations later, how did Johanna Fernandez get interested enough in this slightly obscure group to memorialize it in what she calls a five-year “labor of love?” Like the Young Lords, Fernandez has a history. Here’s what she told me about herself:

Johanna Fernandez: I grew up in the Bronx during the crack epidemic, at the height of the urban crisis. My parents are immigrants from the Dominican Republic, working-class people, and I became radicalized in part because of my dual identity.

At home, I was in the little Dominican Republic, but even though Dominicans are among the darkest people in Latin America, they don’t consider themselves black. In the world, though, in the public sphere, I was identified as black. So the double-consciousness I had to develop at a very early age made me wonder about how these different ways of understanding the world coexist.

My parents weren’t political at all. My father was orphaned when he was eight. But although he came here fleeing poverty and a dictator, my father had developed a really moral core, a sense that a few people shouldn’t have such great wealth while so many have so little.

I think I decided when I was young to become a professor because it would allow me to understand the world and its problems.

I knew absolutely nothing of what it would take to become a professor. My mother graduated high school, my father has a third-grade education, and I started work when I was like 14, as soon as I got my papers. But I interviewed my professors and asked them, ‘What exactly is this thing called a PhD and what do you do to get there?’ I didn’t even know what an Ivy League school was. But my history teacher had gone to Brown, so she recruited me to apply there.

So I got to Brown, coming from the Bronx, and the class and race differences were epic. I studied black women writers, so African-American literature and history were critical to my political evolution.

I was in Brown’s first class admitted with a “need aware” policy. But the policy was reversed because they saw it was going to cost millions to finance students who couldn’t afford to be there. So we took over a building.

This was one of the largest student protests in the 1990s. More than a thousand students took over University Hall — about 250 of us were arrested. See, I was fueled by the notion that my peers in the Bronx could very well have been students at Brown, but there was this system of race and class inequality that kept people like me from getting this incredible education.”

A painting by Sophia Dawson exhibited in a Bronx Museum of the Arts installation of art curated by Johanna Fernandez that tells the story of the Young Lords.

So, from the Bronx to Brown: the takeovers continue. Because, funny thing about that “system of race and class inequality”? It’s still around. That part of history keeps repeating itself, while unknown centuries of effort by people like Fernandez and groups like the Young Lords to stave off poverty, overwork, and psychic erasure vaporizes in the wake of high-rise condos in the Bronx and Old Navy stores along 125th Street. The lasting accomplishment of the ¡Presente! exhibits is that they’ve captured some of that history before it could completely evaporate. Who, knows, the exhibits may spur even a little change, themselves.

A few days ago, my 20-something friend Camilo, visited ¡Presente! in the Bronx. Camilo came to this country as a child from Colombia, probably a little after Fernandez took over that building. He texted me a photo he took of the Young Lords’ 13-Point Program, then wrote: “This is terrible. Such an amazing vision. We haven’t been able to make this happen.”

Look for Johanna Fernandez’s book about the Young Lords, “When the World Was Their Stage: A History of the Young Lords Party, 1968–1976,” due to be published soon by Princeton University Press. Susie Day is the author of “Snidelines: Talking Trash to Power,” published by Abingdon Square Publishing.