Count Henry Velandia and Josh Vandiver among the lucky ones.

On May 6, Velandia, a 27-year-old salsa dancer and instructor who moved to the US from Venezuela in 2002, faced a deportation hearing, the latest in a series of ominous steps initiated by the Department of Homeland Security in 2009.

Velandia and Vandiver, a Colorado-born, 30-year-old Ph.D. student in political theory at Princeton, married in Connecticut last August. In advance of the May hearing, the couple’s attorney, Lavi Soloway, argued that Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), a unit of Homeland Security, should exercise “prosecutorial discretion” in handling Velandia’s case.

The attorney cited the men’s marriage, the dangers they would face as a binational married gay couple in Venezuela, Velandia’s standing as a law-abiding dance instructor in Princeton, and the February decision by the Obama administration to stop defending the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) in court. If the men’s marriage were recognized as it would be if they were a different-sex couple, Velandia would have a unfettered path to permanent residency.

ICE denied Soloway’s request, but the Immigration Judge in Newark gave Velandia a seven-month reprieve, scheduling another hearing in December. The Venezuelan man was fortunate that in cases that don’t involve undocumented immigrants who have run afoul of the law, the US government often moves slowly in removal proceedings.

The following month, the couple received even better news. On June 9, Jane Minichiello, chief counsel in ICE’s Newark office, reconsidered the request for prosecutorial discretion, stating Velandia’s removal “is not an enforcement priority at this time.” The following week, Immigration Judge Alberto Riefkohl accepted the government’s motion to close the proceedings against him.

According to Soloway, that move marks the first time deportation efforts against a same-sex spouse have ever been formally halted.

On July 19, Velandia received a one-year employment authorization document that will enable him to work legally and, for the first time, travel domestically by plane, privileges granted him because of Vandiver’s spousal green card sponsorship application — something likely to be turned down due to DOMA.

“I can breathe again,” Velandia said in a July 17 interview at Gay City News’ offices. “I can start dreaming again.”

Then, noting that nothing has changed in the laws governing his status in the US or his right to permanent residency, he added, “I know it’s not the end of the tunnel.”

Indeed, it’s not — not for Velandia and, more urgently, not for thousands of other same-sex undocumented partners of American citizens. ICE’s determination in this case was discretionary, and there is no guarantee the couple’s welcome breathing room will not be interrupted at any given moment in the future.

Still, time is likely on Vandiver and Velandia’s side, in good measure due to extraordinary changes in the national dialogue about DOMA and the Obama administration’s posture toward defending and enforcing it.

In February, Attorney General Eric Holder informed Congress that the administration was no longer prepared to argue on behalf of the 1996 law’s ban on federal recognition of valid same-sex marriages in court, stating the administration view that it unconstitutionally violates the equal protection rights of gay and lesbian couples.

The attorney general assured Congress the administration would continue to enforce DOMA, and the Republican leadership in the House stepped into the breach, hiring outside counsel to defend the statute in place of the Justice Department.

Since that time, however, DOJ has indicated it will no longer oppose joint bankruptcy filings by same-sex married couples — an argument that even John Boehner’s House Republicans are unwilling to engage — and on July 1, the government filed a brief, in a case involving the denial of same-sex spousal benefits to a federal court employee, affirmatively declaring that DOMA is unconstitutional.

In May, Holder himself intervened to block the deportation of a New Jersey same-sex civil union partner, Paul Wilson Dorman, directing the federal Board of Immigration Appeals to reconsider the case with a specific focus on “how the constitutionality of DOMA is presented in this case.”

No doubt influenced by the shifting posture of the government itself, several Immigration Judges have offered respite to same-sex married couples. Last month in Baltimore, a judge, of her own volition, reopened the pending deportation of an El Salvadoran man married to an American man, citing “the interest of justice” and noting “current policy and/or legal developments” regarding same-sex spouses.

Last week, a San Francisco Immigration Judge gave the government 60 days to decide whether to use prosecutorial discretion to halt deportation proceedings against another Venezuelan same-sex spouse of an American. If ICE declines to do so, the man will be given until September 2013 to report back to court, a clear sign of where the judge’s sympathies lie.

These advances, however, are not being seen uniformly across the immigration spectrum — and there have also been setbacks. In April, the US Citizenship and Immigration Services denied the green card sponsorship application of a Queens woman on behalf of her Argentine-born wife, citing not only DOMA, but also a separate 1982 precedent (see related story),

Velandia and Vandiver are mindful of their relative good fortune, the continuing tenuousness of their status, and the hardships faced by other couples in their exact situation.

“I think we really do feel a responsibility,” Vandiver said of their commitment to speak out on behalf of the many other binational couples they have met over the past year. “We could hardly hear their heartfelt stories and not be moved to act.”

Acknowledging that the government’s action in their case was “ad hoc,” he added, “We are seeking articulation of a national policy.”

Last fall, describing himself as “a reclusive scholar,” Vandiver said, “I don’t want to be an activist.” This past weekend, he sounded a starkly different tone, saying, “I do think I feel like a more willing activist. A lot of what we have done has been hard, but it has also been more rewarding and satisfying than anything I’ve ever done.”

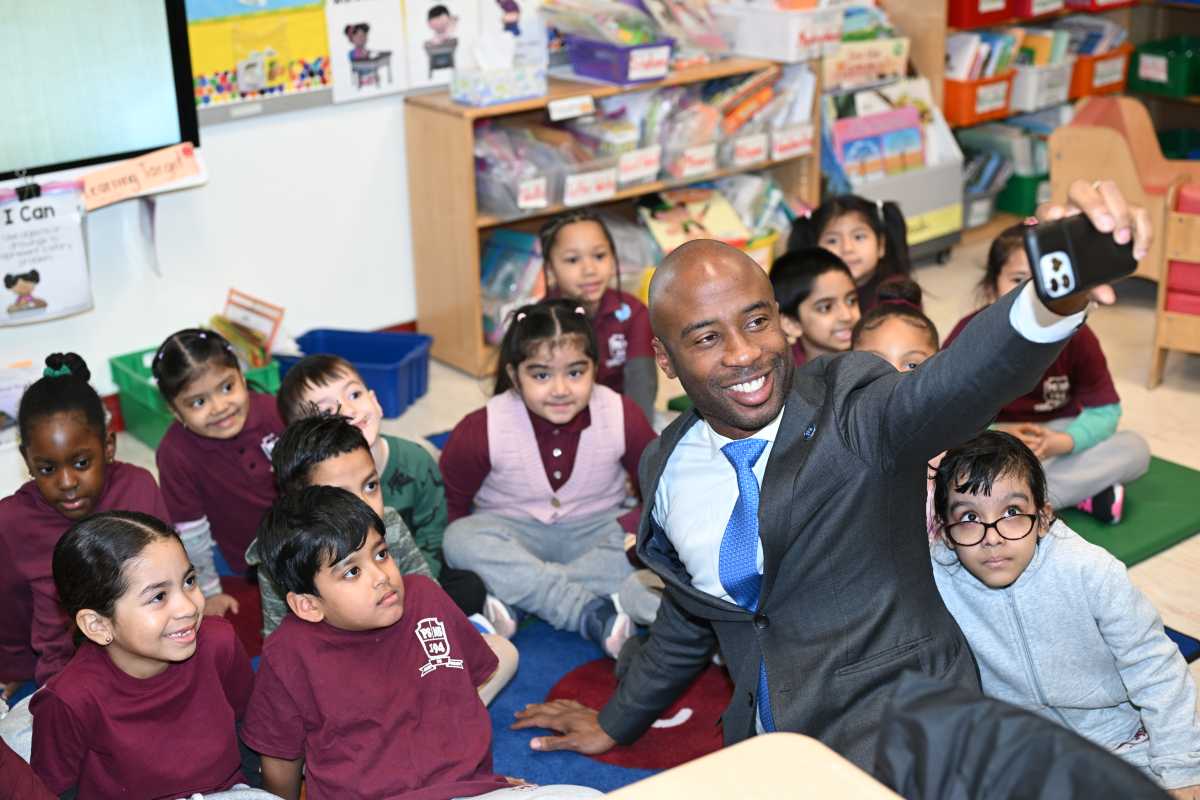

For Velandia and Vandiver, a lot of that work has been a very personal telling and retelling of their own story — in what they estimate have been dozens of newspaper and television interviews.

“People are inspired because we are fighting for love,” Velandia said.

The couple is convinced they would not be where they are today — temporarily, at least, out of harm’s way — were it not for their visibility. Ultimate victory, for themselves and others, Vandiver said, will only arrive if the issue “becomes about the couples, not some abstract argument.”

In part through their work with Soloway’s Stop the Deportations project, the couple have met many others in the same boat they are.

“It’s intense to see how many couples there are like us,” Velandia said.

In the past, much of the broader effort by activists to win justice for binational couples was pinned on immigration reform, but the focus of Velandia and Vandiver’s hopes are in overturning the Defense of Marriage Act.

“We would like to put all our energy into repealing DOMA,” Vandiver said. Then noting the thousands of same-sex couples likely to marry soon in New York, who like them will not have their unions recognized by the federal government, he added, “We want to work with the broader community of married same-sex couples across the country.”