While religion in modern days may be more welcoming to LGBTQ members than in the past, a trip uptown to Manhattan’s Fort Tryon Park shows a queer sensibility has long been there. From Saint Sebastian to same-sex couplings among the holiest of Christian figures, the Metropolitan Museum of Arts’ Spectrum of Desire: Love, Sex, and Gender in the Middle Ages — on view through Sunday, March 29, 2026, at its medieval and religious art-focused Cloisters branch — is a surprisingly queer delight.

Co-curated by the Met’s Dr. Melanie Holcomb and Dr. Nancy Thebaut a professor at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom, the show journeys through a decidedly sexual world, with about 75% of the objects coming from the Met’s collection along with items borrowed from other American institutions. Anyone who knows Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales will already be familiar with this world, yet to see it expressed visually through art, illuminated texts, and other late Medieval and early Renaissance objects is transcendentally assumption shattering.

Holcomb said the show had “a very long gestation,” adding that certain pieces in the Met’s collection struck her, leading to “a cumulative list of objects that were fascinating to me, that seemed to be dealing with themes of gender and sexuality. But like, what was that? Could these ever be a show?”

Among the objects is an early 15th Century illustrated manuscript evoking what seems to be a Monty Python skit. Holcomb said, “It shows the story of Saint Jerome, the church father, being tricked into wearing a woman’s dress and then being mocked for it in a monastery setting.”

As long-time friends and colleagues, Holcomb said Thebaut “too had been kind of collecting Met objects, so it was really sort of a bar conversation that had us bring” the elements together.

Holcomb added, “this lens of gender and sexuality has been kind of a thread for medieval historians, medieval art historians, medieval literary historians. This has been in the field for a while, and yet there have really been no exhibitions that put it all together, no sort of exclusively object focused, big-picture narrative, and we came to realize it was a fantastic lens to look at our superb collection, and sort of the right project for the right moment.”

Among these is a seemingly simple small leather box from the 14th century, which, on close inspection, reveals scenes of a pansexual nature, adorned with both opposite and same-sex couples.

“How can we explain this?” Holcomb said. “So, there were a lot of puzzles that I just kept accumulating.”

One of the most striking pieces and what Holcomb called “the culminating object in the show” is a 14th century German statue borrowed from the Cleveland Museum of Art depicting John the Baptist lying his head on Jesus’ chest, a touching sense of kinship and intimacy between them. The plaque describes how medieval viewers, especially in monastic settings, would have seen their relationship as a form of marriage “with Jesus in the role of the groom” and one that “stretched gender roles and sexual identities.”

The medieval world interpreted union across genders, according to Holcomb, in ways we might today see through the lens of same-sex marriage.

“Marital union is for the medieval world, one of the best and richest ways to talk about unions of any kind,” she said, adding that such a view “encompasses a sexual relationship, a partnership, even kind of its legality.”

The idea was furthered in the medieval period, she said, as “ultimately a model for union between a Christian devotee and God.” It is among the ways that “medieval people love to pile on meanings.”

Nearby, another 14th century statue, The Visitation, depicts the Virgin Mary pregnant with Jesus, holding hands with her cousin Elizabeth, simultaneously pregnant with her own child, who would become John the Baptist.

Created for a Swiss convent, it conveys a similar message of friendship and marital union, its plaque stating the “quiet allusion to the marital bond offers a sense of same-sex community, spiritual kinship, and, potentially, desire.”

Still, the curators caution not all of the same-sex coupled imagery should be interpreted as medieval enlightenment. Thebaut highlighted a late 15th century Dutch wooden statuette base of Eve with the serpent, here depicted as female, and with their matching hairstyles, almost her twin. “Medieval people,” Thebaut said, “would have understood this in relation to same-gender desire, specifically a condemnation of same-gender or same-sex desire.”

The statuette embodies what she said medieval theologians call “sodomia,” encompassing more than sodomy, to mean “same-gender desire. It can mean heresy. It can mean gender transgressions as well.” She added that similar depictions of this “erotically charged moment,” what many theologians call “Ground Zero of sodomy” is duplicated throughout medieval Europe as a warning against same-sex desire and temptation.

Wall panels, plaques and the catalog detail these intriguing and contrasting ideas on same-sex coupled imagery throughout the period.

The curators also highlighted various scholars, including the late John Boswell, among the first to discuss early medieval same-sex pairing. Thebaut said the show builds on decades of scholarship in the area, noting that individuals like Boswell “have been so foundational for this field. He was a pioneer in this area. Much of the work on sex and sexuality in the Middle Ages remains indebted to him.” She also mentioned that New York University’s Dr. Carolyn Dinshaw research helped inform the exhibit.

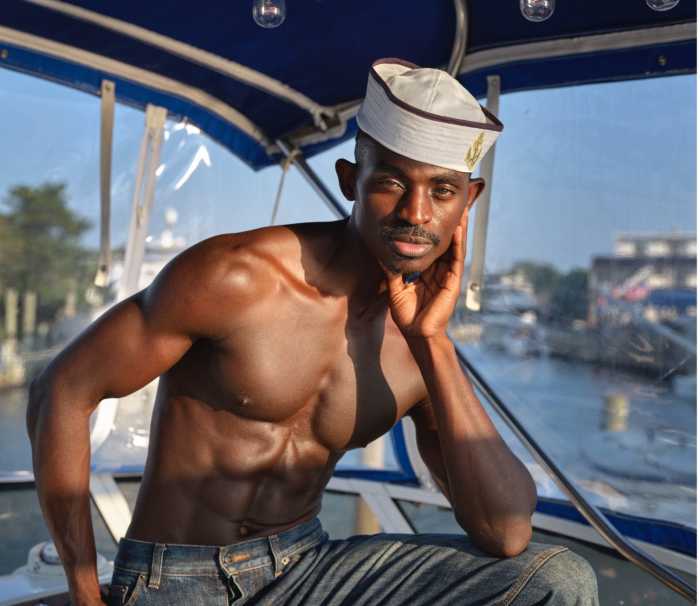

And, of course, no exhibit encompassing religion, art, sexuality and same-sex desire can leave out Saint Sebastian, viewed in the past few centuries, including by Oscar Wilde, as a queer icon. Here, a late 15th Century statue of Northern European provenance recently restored by the Met’s conservation specialist Lucretia Kargere is on display, pubic hair peeking from the loincloth. An early Christian martyred in the 3rd Century, the plaque describes him as “an emblem of queer beauty, erotic vulnerability, and hope in the face of suffering.”

Saint Sebastian is placed within the exhibit’s Beautiful Bodies section. Thebaut said he became “an important gay icon over the years, I think because of the often-eroticized way that he’s depicted with very little clothing.” The connection became more relevant, she said, “during the height of the AIDS crisis when Saint Sebastian became an important figure in the face of life suffering and endurance.” This, she added, mirrored how “Sebastian in the Middle Ages was especially venerated during the plague.”

The catalog includes an essay by Ohio State University researcher Dr. Karl Whittington asking museum-goers to imagine themselves in the role of the sculptor, creating such an icon of beauty. The essay is one of several with queer themes.

Thebaut also emphasized that while we think of issues like gender transition as new, throughout the medieval period and beyond, research shows that gender was treated as fluid, including for how the saints were depicted.

“Saints like Theodore, Theodora, Marina, Marinos, we’ll go forward on this. So, I think that people are surprised to learn that over 30 saints changed their gender presentation over the course of their lifetime, that artists represented them, that authors change pronouns when talking about them,” she said, adding, “I think that for many people that can invite them to think more expansively about the history of gender.

It is in this way that these centuries-old pieces continue to speak to us despite being from a period that is so different and yet at the same time, similar to where we are now, with sexuality, religion, society, and authority heatedly debated in the news.

“It’s not just historians now and academics who care about it. America cares about these topics,” Holcomb said.

Spectrum of Desire Love Sex and Gender in the Middle Ages will run through Sunday, March 29, 2026.