Alex Hibbert and Mahershala Ali in Barry Jenkins’ “Moonlight,” based on a play by Tarell Alvin McCraney. | A24

“Moonlight” is Barry Jenkins’ extraordinary film adaptation of Tarell Alvin McCraney’s play “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue,” which takes its title from a nighttime scene of teenage sexual experimentation on a Miami beach.

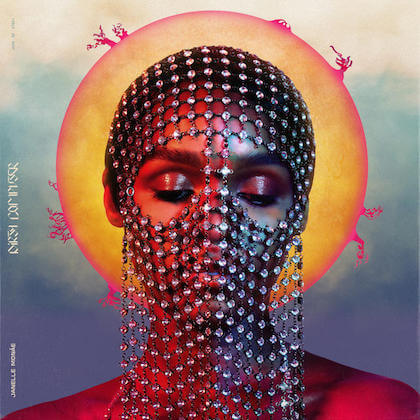

Before the film gets there, Jenkins introduces the main character, Chiron, as a nine-year-old boy (Alex Hibbert). Nicknamed Little, he is escaping from bullies from school, who threaten to “kick his faggot ass,” by hiding out in a dope hole when he is discovered by Juan (Mahershala Ali), a local drug dealer. After Juan takes him home to his girlfriend, Teresa (Janelle Monáe), Little doesn’t speak much but he does eat. When Juan returns Little to his mother, Paula (Naomie Harris), she makes clear she doesn’t want Juan involved in her son’s life. Paula, it is soon revealed, is one of Juan’s customers.

Juan, however, becomes a kind of father figure to the young boy. A very tender scene has Juan teaching Little how to swim in the ocean, “baptizing” him. He later tells Little, “At some point, you have to decide for yourself who you are going to be. You can’t have anyone else make that decision for you.” These words resonate throughout the film as Chiron grows into adulthood, repeatedly forced to face his true nature.

Barry Jenkins explores black gay masculinity, sexuality in coming of age tale

What is also particularly compelling about “Moonlight” is how much we learn about the characters through their internalized — rather than expressed — emotions. Jenkins deftly captures unspoken empathy between characters, allowing viewers to appreciate why they matter to each other.

Little also forges a strong relationship with Kevin (Jaden Piner). Helping Little prove he isn’t “soft,” Kevin wrestles with him in the grass, and the sexual tension between the two — which plays out over the course of the film — is already palpable.

The second act of “Moonlight” focuses on Chiron (Ashton Sanders), now a teenager, seemingly living in constant fear. His mother’s drug habit has escalated out of control, and in a particularly uncomfortable scene she demands money from him. Chiron is also still being bullied at school. His erotic dreams about Kevin (Jharrel Jerome) become reality in the scene on the beach that involves the boys kissing and more.

What transpires after this romantic encounter moves “Moonlight” into its third and most compelling act. Chiron (Trevante Rhodes) has now assumed Kevin’s nickname for him, Black. When he gets a call out of the blue from Kevin (André Holland), Black meets his old friend in a diner where Kevin works. As the men reconnect, “Moonlight” becomes transcendent.

It would spoil the pleasures of this intimate, deeply affecting film to discuss too many details — in part because so much of the story happens inside each character or off screen. One character disappears without explanation, leaving audiences to draw their own conclusions about their fate. Some scenes, such as Paula yelling at her son, are presented twice, to emphasize, even magnify their importance.

Jenkins seems less interested in plot than he is in creating a raw space where the film’s potent themes about power and masculinity can be explored. “Moonlight” sensitively investigates what it means to be black and gay amidst a world that revolves around the sale and use of drugs. We understand the characters from quiet moments — such as Little preparing a bath for himself or teenaged Chiron getting a lesson on how to make a bed from Teresa, or when Kevin and Black sit across from each other in a diner. Juan may be a tough drug dealer, but he practically melts when nine-year-old Little looks up at him and begins a series of tough questions by asking, “What’s a faggot?”

Jenkins is not afraid to explore what makes Chiron cry, but he also shows us a shocking act of violence that proves a catalyst in Chiron maturing. Seeing the shy, confused child and later the haunted teen transform into the adult Black, who still grapples with his sexuality and who he is, is remarkable. The three actors who play this one character are all indelible in the role.

If Jenkins’ film has a drawback, it is that Teresa and Paula are presented as mother/ saint and crack whore stereotypes, respectively. The lack of nuance here detracts from the film’s overall impact. But in a moving, empowering, even necessary “Moonlight,” this is a minor complaint.

MOONLIGHT | Directed by Barry Jenkins | A24 | Opens Oct. 21 | Angelika Film Center, 18 W. Houston St. at Mercer St.; angelikafilmcenter.com/nyc | Lincoln Plaza Cinema | 1886 Broadway at W. 62nd St; lincolnplazacinema.com