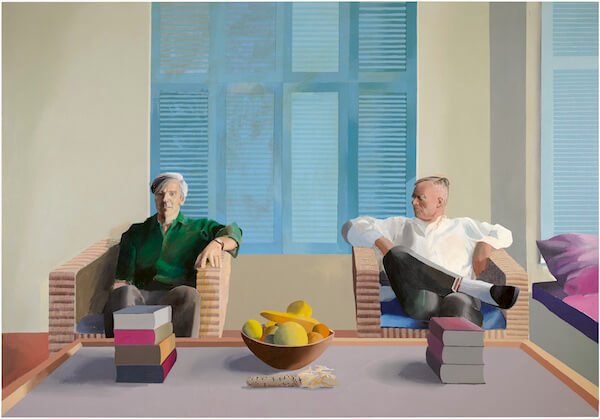

Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld (right) and his lover Tao Li at the 1932 World League for Sexual Reform Conference in Brno, Czechoslovakia.| ARCHIV DER MAGNUS-HIRSCHFELD-GESELLSCHAFT E.V., BERLIN

To speak about the modern LGBTQ movement is to use the intellectual and political tool kit created by the groundbreaking gay sexual researcher Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld.

Germany’s Magnus Hirschfeld Foundation is slated to hold an extraordinary ceremony in Berlin on May 14 marking the 150th birthday of Hirschfeld, who was born on that date in 1868 in what was then Kolberg, Prussia, and is now part of Poland.

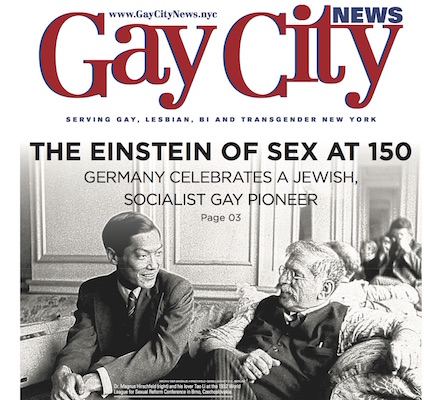

Hirschfeld, a German-born Jew, was termed “The Einstein of Sex” by a journalist describing his achievements within the field of sexology. After Hirschfeld met with the German Jewish physicist Albert Einstein in California in 1931, the phrase gained traction. “Einstein is the Hirschfeld of physics,” was Hirschfeld’s piquant response.

Germany celebrates the Jewish, Socialist gay pioneer Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld

Hirschfeld was one of the most hated men among Hitler’s followers during the nascent phase of the Nazi movement. His troika of identities — Jew, Socialist, and gay man — infuriated them. Hirschfeld had left Germany by the time Adolf Hitler maneuvered himself into the chancellorship in January 1933. Motivated by anti-Semitism and homophobic rage, the National Socialist Students’ League, in that same year, stormed Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Research in Berlin and plundered its material. The young Nazis yelled “Brenne Hirschfeld” (“Burn Hirschfeld”) as they obliterated what was at the time the world’s most important repository of research material on sexuality.

While Hirschfeld is largely forgotten in the US today, the LGBTQ culture and political work connected to him are ingrained in American culture. The gay English-American writer Christopher Isherwood stayed at Hirschfeld’s Institute in 1929 and 1930, and his novel “Goodbye to Berlin” — the basis for the musical play and film “Cabaret” — familiarized the broader society with Germany’s thriving underground of same-sex relations, bisexuality, and gender nonconformity. Harry Hay, the founder of the Mattachine Society in Los Angeles in 1950, also admired Hirschfeld.

Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld in his library. | ARCHIV DER MAGNUS-HIRSCHFELD-GESELLSCHAFT E.V., BERLIN

To understand more about the man, Gay City News surveyed a spectrum of leading Hirschfeld scholars, German LGBTQ activists, journalists, educators, a federal justice minister, a Green Party politician who spearheaded the fight for marriage equality in Germany, and a prominent musician about the legacy of Hirschfeld in his native country and across the globe.

Professor Dagmar Herzog, a City University of New York Graduate Center historian who will deliver a talk on Hirschfeld at the May 14 remembrance in Berlin, has written extensively on sexuality studies and fascism. She told Gay City News that Hirschfeld “was ‘the first’ in so many ways: the founder of the first gay and lesbian rights movement, launcher of the first campaign to decriminalize homosexuality, first vocal and empathetic defender of transgender rights (including facilitating early gender confirmation surgeries), first to open an institute of sexual science, first to start a medical journal dedicated to sexual minorities, first to use film and pamphlet literature and public talks to combat popular anti-homosexual prejudice, first to develop support groups for same-sex-desiring individuals in order to facilitate self-acceptance.”

Herzog added, “He was way ahead of his time in thinking affirmatively about both same-sex and gender expression issues, he was a queer thinker avant la lettre. He made alliances with women’s rights activists and fought for a sexual morality based on consent and self-determination. And he was deeply humane, and incredibly courageous — continuing the struggle for sexual rights for all even in the face of outrageous and constant anti-Semitic slander, death threats, and brute physical violence. He modeled both generosity and guts.”

When asked why Hirschfeld is not widely known today, Herzog answered, “There are multiple factors. Most important was the thoroughness with which right-wing, anti-Semitic homophobes — and then especially the Nazis — managed to taint Hirschfeld’s work as dirty. From the very beginning his campaign to decriminalize male homosexuality was described as ‘an aggressive act of Jewish horniness’ (a quote from the philosopher Eugen Dühring in 1897); others referred to him as the ‘most shameless and base poisoner of the Volk [People].’”

She added, “It is telling that the archive and library in his Institute of Sexual Science — with tens of thousands of precious photographs, patient files, questionnaire responses, and sexological texts — was the first target of the Nazi book burnings in May 1933. Hirschfeld died in exile in 1935.”

The Berlin-based Magnus Hirschfeld Foundation — a government-created organization founded in 2011 — seeks to revive contemporary awareness of Hirschfeld’s life, work, and motto: “Through Science to Justice.”

Members of the National Socialist Students’ League parading in front of Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Research in Berlin on May 6, 1933, prior to their attacking it, looting and setting on fire its archives. | UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

Jörg Litwinschuh, the executive director of the Foundation, outlined to Gay City News how its work has entered the mainstream in Germany. With a staff of only eight and a publicly funded budget of 500,000 euros per year (roughly $600,000), Litwinschuh said he worked with the Research Centre for Contemporary History in Munich to include the persecution of homosexuals in its program. The Research Centre had not previously devoted serious work to the Nazi movement’s destruction of LGBTQ life during the 12 years of National Socialism.

Commenting on the academic gaps and lack of knowledge among young people about the persecution of gays, Litwinschuh said, “Each generation must learn anew. The great challenge is how can one reach young people and compete with Facebook. We need to transmit the stories over tablets and smartphones.”

The Hirschfeld Foundation has launched an “Archive of Different Memories” that documents via video the life histories of LGBTQ people in Germany and the now-defunct German Democratic Republic.

Litwinschuh, a high-energy activist who got his start combating homophobia within the Catholic Church in Germany, said that the multimedia testimonies from Holocaust victims at Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education at the University of Southern California furnish a “good example” of a pedagogical approach appropriate for the LGBTQ community. He added, however, “We do not only want to present victim stories and not only be reduced to sexuality.” He stressed the importance of school curriculum pointing to rainbow families and not only persecuted gays.

Litwinschuh explained that the Hirschfeld Foundation’s educational work has reached into Germany’s national pastime: soccer. Under the title “Soccer for Diversity,” the Hirschfeld Foundation will work to provide educational assistance on welcoming LGBTQ players to soccer association managers, trainers, and fans.

Volker Beck, a Green Party politician who played a key role in the fight for equal marriage rights in Germany that succeeded last year, told Gay City News, “Hirschfeld built the first effective organization for the liberation of homosexuals from criminal liability. After the tragic failure of his predecessor, Karl-Heinrich Ulrichs, he laid the foundation for the later homosexual movements.”

Ulrichs (1825 – 1895) was an openly gay writer who fought unsuccessfully to decriminalize same-sex relations. Litwinschuh termed Hirschfeld and Ulrichs the two “great-grandfathers of the gay movement.”

Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld (right) and his lover Tao Li in exile in Nice, France, in 1934, one year before Hirschfeld’s death. | ARCHIV DER MAGNUS-HIRSCHFELD-GESELLSCHAFT E.V., BERLIN

Proudly noting that he has a Hirschfeld business card, Beck said he admires his “pioneer spirit and also the talent of Hirschfeld to position our concerns via social democracy in the societal political discourse of his time.”

Beck, who teaches religious studies at Ruhr-University Bochum, said Hirschfeld’s life is neatly captured by the famous Talmud statement: “It is upon us to begin the work, it is not upon us to complete it.”

For today’s queer community, Beck said, “LGBT human rights must be a topic with all other human rights questions. The human rights of LGBTs are not issues from an orchid family of the human rights agenda that one can turn over to a few particular specialists. One must do more for the entire strengthening of the LGBT human rights defenders in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America.”

Hirschfeld himself thought not only locally but globally, as well, about LGBTQ rights. In 1930, he began a world tour to study human sexuality.

“My field is the world and not only Germany and Europe,” said the sexologist.

The world trip crisscrossed Japan, China, the Philippines, Indonesia, Singapore, Ceylon, India, Egypt, then-British Mandate Palestine, and the US.

“There are not two lands and two populations with a complete match of sexual characteristics,” he wrote at the time.

Germany’s federal minister of justice and consumer protection, Dr. Katarina Barley, told Gay City News, “Magnus Hirschfeld stands for the courage and societal vision to develop and engage to fight for [LGBTQ rights]. His educational drive formed his life motto: ‘Through Science to Justice.’”

She added, “Today our society needs people who leave the common pattern of thought and do not allow themselves to be frightened by resistance or rejection.”

The German Justice Ministry is the principal funder of the Magnus Hirschfeld Foundation. Germany’s parliament — the Bundestag — enacted legislation to provide that funding.

Ralf Dose, the head of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society in Germany, is arguably the world’s leading Hirschfeld scholar, and authored “Magnus Hirschfeld: The Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement.” Litwinschuh said the effort to breathe life and fire into Hirschfeld’s legacy owes a tremendous debt to Dose’s 30 years of scholarship about the sexologist.

Dose told Gay City News, “I came out of the West Berlin gay movement and I began in 1982/ 1983 to focus my work more closely on Magnus Hirschfeld and the Institute of Sexual Science… It was always important for me that it did not only deal with Hirschfeld alone. In an institute and within a movement like the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, many people are active. Social and sexual reforms are never the work of an isolated individual. The rediscovery of an entire network of social, political, personal, and sexual connections continues to fascinate me today.”

Founded by Hirschfeld in 1897, the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee was and is widely considered the first world’s first LGBTQ organization. The Committee sought, with a petition campaign, to repeal Germany’s infamous paragraph 175 penalizing gay sexual behavior. Among the petition’s well-known signatories were Albert Einstein and the writers Hermann Hesse, Thomas Mann, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Leo Tolstoy.

The May 14 remembrance for Hirschfeld will feature the talented singer and actress Vivian Kanner, who told Gay City News she considers it an honor to contribute a musical performance to the event.

“Magnus Hirschfeld was an important personality of the last century and is for me to be mentioned in the same breath as Sigmund Freud,” she said.

Kanner, who is a lesbian, warned about the failure to integrate refugees and migrants into German social mores.

“It is due to massive immigration to Germany from different cultural circles, in which homosexuality is punished with the death penalty and Jews and Israel are viewed as the enemy… that on the German street there are once more attacks on homosexuals and Jews,” she said.

Since 2015, German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government has admitted more than a million refugees and migrants from mainly Muslim-majority countries. The April attack by a Syrian refugee on an Israeli Arab because he wore a kippa on a Berlin street triggered headlines in the German and foreign media. But in 2016, in an incident largely ignored by even the German media, three young men from North Africa were arrested in the western German city of Dortmund for stoning two transgender women.

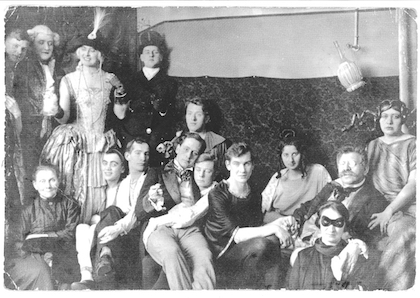

An undated costume party at Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Research in Berlin. | ARCHIV DER MAGNUS-HIRSCHFELD-GESELLSCHAFT E.V., BERLIN

Kanner said it is vital that “in German integration courses, the attendees are not only introduced to recycling and the need to avoid disturbing the peace, but it is of great importance to convey to them democratic, free, tolerant Western values.”

The Hirschfeld Foundation sought as early as 2015 to draw attention to the problems facing LGBTQ refugees. That year, queer refugees from Syria, Lebanon, and Russia appeared at a Foundation fundraiser. In 2016, the Foundation launched its “Refugees and Queers” project to aid LGBTQ asylum seekers. A gay Syrian leads the project, said Litwinschuh, who pointed to data showing that 10 percent of the recent refugee population is LGBTQ. He stressed that more resources are needed to address their needs as well as the challenges of integrating the broader refugee population.

“Many homosexuals have fears of non-integrated refugees,” he said.

Lucie G. Veith, who campaigns to advance the rights and dignity of intersex people in Germany, told Gay City News, “As an intersexual-born person… this is what I have learned from Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld: educate and do not let up, because knowledge and persistence will defeat injustice and misuse of power.”

Veith emphasized that “structural violence in medicine is not an unknown topic to most intersexual people.” The genitalia of intersex children are often destroyed through a so-called “normal sex” plastic surgery operation so that they conform to societal conventions, Vieth said, adding, “Discrimination because of sex has not been eliminated.”

Jan Feddersen, an author and an editor with the taz daily newspaper, told Gay City News, “Hirschfeld advocated politics that went beyond the sect-like LGBTI niches. He wanted to have success and not only in his community.”

When asked to assess how much the German government has done to combat persecution of LGBTQ people, Feddersen, who is the chair of the Elberskirchen-Hirschfeld House Association, a public forum for queer research, learning, and culture in Berlin, said, “Not enough. But the government has already done a lot. The government opened a room at the embassy in Moscow for conversations with Russian LGBTI activists.”

Feddersen’s organization also honors Johanna Elberskirchen (1864-1943), a German lesbian activist who campaigned for the rights of gays and lesbians. Feddersen views the Elberskirchen-Hirschfeld House as a “queer cultural house in the tradition of the Weimar Republic.” It was under the liberal, democratic order that Weimar struggled to maintain that German arts and culture experienced a rich renaissance.

Dr. Norman Domeier, a historian at the University of Stuttgart who has written about homophobia in the German Empire that preceded the Weimar Republic, said that what the world now understands as the LGBTQ community, Hirschfeld “thought out. But Hirschfeld was not only a pioneer for the rights of disadvantaged groups, he wanted to also liberate heterosexuals who he saw as repressed by the moral spirit of the time.”

Hirschfeld’s life spanned Imperial Germany, the Weimar Republic, and the first several years of the Nazi regime. At 150, the Einstein of Sex’s legacy still resonates among many in Germany today. The pressing question is whether the advances his early work made possible will spread beyond the borders of Western liberal democracies and achieve Hirschfeld’s vision of transforming the entire world.

Benjamin Weinthal is a Berlin-based journalist who reports on the LGBTQ community in the Middle East and Europe. He is a research fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. Follow Weinthal on Twitter @BenWeinthal.