UK’s Propeller Company ushers out winter with Shakespeare in Brooklyn

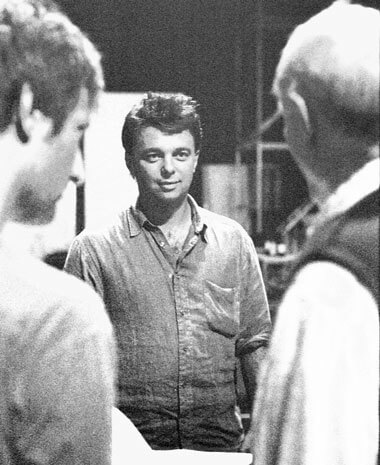

Don’t tell British director Edward Hall about same-sex marriage. He’s been rehearsing Shakespeare’s doozy of a wedding play, and what’s more, doing it with an all-male company. Still, it would be a mistake to look for his acclaimed Propeller Company to storm the marriage license bureau after their production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

After all, they’ve had enough of a tussle navigating Homeland Security in a process Hall describes as “queuing outside the American embassy in London for two hours in the pouring rain” topped off by “five hours of an extremely complex visa application process everyone now has to do in person.”

Gay marriages and immigration issues aside, Hall refers to men playing women on stage as “a very traditional aspect of performing the play.” This “gender fuck” perspective speaks to Hall’s dramaturgical approach, reminiscent of Dogma 95, the innovative artistic group founded to preserve cinematic integrity. “When I first directed a Shakespeare play, it looked good, everything in the right place, people seemed to enjoy it, but somehow I couldn’t smell it,” Hall explained. “So I wanted to do a show where I put on cultural reference points that I recognize and yet not use huge amounts of technology—we create all our own music and sound live and do all our own scene changes—-to see what would happen when you mixed those ideas with a group of like-minded people in a room and give the story-telling aspects of the performance back to the actors. They do everything, sometimes even the lighting.”

For productions staged in England, Hall Watermill Theatre isn’t in London, but rather “a very small, 20-year-old community theater with bones dating back to the 19th century. It’s 50 miles west of London in the middle of the countryside and was originally a real working watermill that’s all wooden inside. The old water wheel is still there. It’s the kind of place you can go and just live there and create work, a bit like Mnouchkine’s Cartoucherie in Paris, but on a very small scale where you can isolate yourself with a group of people and do something a little vocational for a while,” the 37-year-old director said, referring to Parisian cheffe de troupe Ariane Mnouchkine who’s running a similar theater out of an abandoned factory in an avant-garde ghetto on the Bois de Vincennes.

Last summer. the director took up residence at London’s National Theater for a searing revival of David Mamet’s “Edmond” that gave stage time to not only Kenneth Branaugh, but, without putting too fine a point on it, Branaugh’s “wanaugh.”

For Hall, it was the short-dicked ticket prices, not the frontal nudity, that attracted him to the National, where he’s an associate director. When it was suggested that London’s ticket prices seem generous compared to New York’s top tier—like the $480 concierge price for “Producers” tickets—Hall snaps, “Not to us, they don’t!” Of the National’s ten pounds admittance he said, “We got a completely new group of people into the theater who could suddenly afford to take three friends. It became very financially accessible. The biggest influence on what people will go and see in London is ticket prices. That might have been the reason for a more vocal response, but I love American audiences because they are so vocal. Our company is hoping they get a very vocal reaction. They love it. They’ll play and jam with the audience whenever they get the opportunity.”

So how to prepare his wooly company for the wilds of the Big Apple? Hall pulled no punches. “We’re looking forward to Brooklyn so much. We’ve been to some pretty weird places already,” he explained, listing Manila, Dakar, Bangladesh, and “Jakarta five years ago during the huge riots there.” Hall added, “I’m sure none of them will even register on the scale compared to Brooklyn. But BAM is a bit of a dream for all of us.”

When asked how his testosterone-fuelled company squares with feminists’ objections, Hall fires back, “The men-playing-women thing I’ve had no arguments about. I’m exploring the plays the way they were written and a director’s task is to serve the writer. If someone wants to do an all-female Shakespeare company, that’s completely up to them. I wouldn’t stop them, but art isn’t something to be pursued through a committee or censored due to a consensus view. We don’t treat the sexuality of the characters in a different way just because it’s a same-sex cast. I’ve directed plenty of different-sex Shakespeare at the Royal Shakespeare Company and elsewhere, and I’m never conscious of changing the way I direct the play because I’m working with an all-male cast. We forget it and just do the play. When it comes to people getting physical with one another, there’s never any self-consciousness when we’re rehearsing, so 99 percent of the time when we do it onstage there’s no self-consciousness from the audience. It’s just a natural extension of the aesthetic as you present it. Trust me, it’s not an issue.”

But there’s still that “wedding” in the play. And while Hall allows that all eyes are on Americans as they debate same-sex unions, it’s not one of the “contemporary touchstones” he’s chosen for this production.

Instead, Hall lists his inspiration as “a mixture of late Victoriana and a Czechoslovakian animator called Svankmajer.” Is that a cop out? “No,” replied Hall. “We don’t hang about. We don’t stop and have a four-hour wedding ceremony. Otherwise we couldn’t get to the Mechanicals’ play. We do all the text and we do it pretty fast. It runs well under the three-hour mark with an interval! So the marriage doesn’t become an issue of same-sex marriage. Rather, it’s an issue from the play that has to do with harmony and reconciliation. The Elizabethans weren’t as hung up on giving everyone labels. They had a more grown up attitude about sexuality. What they were fascinated by, certainly in the theater, was debating the nature of love.”

His young daughter was there as we spoke and Hall mentioned that his own upbringing was conditioned by being the son of a famous director, Sir Peter Hall. “If you do something good, people say, ‘Oh, of course, he’s Peter Hall’s son’ and if you do something bad, people say, ‘Oh, of course, he’s Peter Hall’s son.’ I’ve been directing plays for 16 years and recently had a major production of mine accredited to him in a major newspaper. It didn’t bother me for more than ten seconds, really. It gives you a fierce objectivity about your work and why you do it.”

Still, this doesn’t mean Hall can’t snap out a pitch for “Midsummer” that would make Barnum blush. “We’re sassy, sexy and in your face,” he said, exuding enthusiasm for a production that fosters an extraordinary connection between audience and performer. “There’s nothing between you and them. They talk to you all night. They sing, make music, every aspect of the performance belongs to them. You get a more intense relationship with the actors, hence a more intense relationship with the play.”

And what of the intense interest with Shakespeare after all these years? For Hall, it’s a matter of the Bard being such “an extraordinary humanist.” And the near-constant speculation about Shakespeare’s sexuality, most recently addressed in “The Beard of Avon” staged by Amy Freed? “If someone proved Shakespeare was bisexual, it wouldn’t surprise me nor make a difference in how I looked at his work,” Hall concluded. “He may have been bisexual, gay, all those things, but great writers don’t give themselves away, only their characters. I don’t think he had issue with someone was who gay, heterosexual, or even, if he was alive today and knew the label, transsexual. To him, it would all have been a different way of expressing the most fascinating of human instincts—love.”