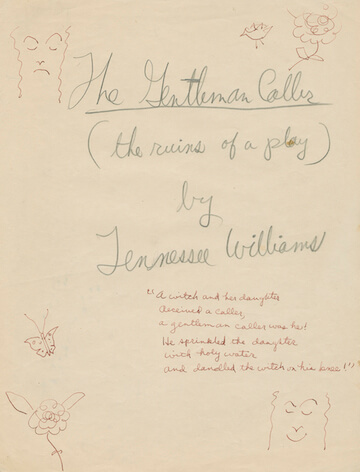

Irving Penn’s 1951 photo portrait of Tennessee Williams. | COURTESY: MORGAN LIBRARY

There it is in a glass case, Marlon Brando’s little black book, tiny and very worn from obvious usage, which he had and then lost during the run of his 1947 star-making “A Streetcar Named Desire,” with an accompanying caption stating that inside he wrote, “On bended knee I beg you to return this. I lost eight others already and if I lose this, I’ll just drop dead!” The actor had left it at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre and it was found by stage manager Robert Downing, but somehow never returned to Brando. And this is but one of the gems in the exhibit “Tennessee Williams: No Refuge But Writing,” which just opened at the Morgan Library.

Such is Williams’ enduring legacy, as exemplified by the endless revivals of his plays, not just here in New York but across the country and, indeed, the globe, he should have an entire museum permanently devoted to him, or even a few, located in the cities he loved and — being complexly Tennessee — also hated: New York, New Orleans, Provincetown, Key West. The fact that he was uncompromisingly gay while his language was and is completely universal is but one of the miracles of his genius. He does, however, speak particularly loud and clear to his fellow gay men, probably more than any other writer, save Shakespeare.

The ultimate gay drama queen’s world revealed

Hardly a day goes by when some life incident I experience — big or small — causes me to immediately flash on pertinent lines he wrote: “I don’t want realism. I want magic!,” “When monster meets monster, one monster has to give way, and it will never be me!,” “Most people’s lives, what are they but trails of debris?,” “I’m just a lewd vagrant,” “Mendacity!,” “No-neck monsters!,” and, most often, “Young, young man…!”

Williams (r.) with his longtime lover Frank Merlo. | COURTESY: MORGAN LIBRARY

His words obviously also deeply affected Laurette Taylor, whose performance as Amanda Wingfield in “The Glass Menagerie,” is considered by everyone who saw it simply the greatest ever. There’s a photograph of her, in costume as Amanda, but she signed it with a quote from the play, instead of a signature. Indeed, Williams’ spirit, as well as his words, haunt our lives, too. What is New Orlean’s French Quarter but one big Tennessee Williams set designed by history? In Manhattan there are all those Broadway and Off-Broadway theaters that housed his work, the Hotel Elysée (nicknamed “The Easy Lay,”), where he lived and died, the YMCA, where he stayed in his early New York years, making full use of the men-only nude days at the swimming pool, and other amenities later extolled by the Village People in popular song.

Contained in one not-enormous room, “Tennessee Williams: No Refuge But Writing” is a small but surprisingly comprehensive exhibit, including journals, letters, poems, scripts, posters, programs, and photographs, which only takes the playwright to the time of his last stage hit, ‘The Night of the Iguana” (1961). Curator Carolyn Vega perhaps discreetly decided not to cover the years that followed before his untimely death in 1983, which occurred when he choked on the cap of a pill bottle he was trying to open with his teeth. Those years saw him experimenting with new, more abstract forms of playwriting, all of which were both critical and commercial failures, as well as sinking deeper and deeper into a morass of drink and drugs that had him taking up with a succession of questionable characters and hanging out at hustler bars on East 53rd Street, and even more louche dives like the Haymarket, on then down-market Eighth Avenue, the kind of a place where the minute you entered, the bartender would scream for your drink order.

Karl Malden, Marlon Brandon, Jessica Tandy, and Kim Hunter in rehearsal for the 1947 Broadway production of “Streetcar Named Desire.” | COURTESY: MORGAN LIBRARY

Unlike, Edward Albee, whose long years in the wilderness, persona non grata on Broadway, finally ended with the comeback triumph of “Three Tall Women” and other new plays until his demise in 2016, Williams was never able to redeem himself. In 1980, I remember being church-mouse poor and yet managing to scrape up enough funds to get a ticket to the opening night of his “Clothes for a Summer Hotel,” because I knew in my bones it would be his Broadway swan song. A phalanx of fabulous, old school boldface names attended to watch the spectacle of an old and fat Geraldine Page, garishly accoutered in a saggy tutu and ballet slippers, impersonate Zelda Fitzgerald. It played 14 performances, and the real end was near.

I had only one encounter with Williams, and it was very brief and completely silent. I’ve always lived on Christopher Street and my first apartment there was, appropriately, on the corner of Gay Street. I was in the habit of getting my Sunday Times from the newsstand around the corner on Sixth Avenue. One gray and drizzly day, I was headed back to my place, Times in hand, when I spotted my idol, alone and huddled in the doorway of the Jon Vie bakery that used to be there. He looked at me and gave me one of those Tennessee Cheshire Cat grins. “Oh God,” I remember thinking. “It’s him! But it’s raining and my paper will get wet! I’ll meet him some other time.” Of course I never did, and it was a lesson forever to me not to be shy if you want to meet someone: seize whatever chance you get to do so because there really may never be another.

Williams’ self-portrait. | COURTESY: MORGAN LIBRARY

The 1970s-80s were hard times, but the Morgan show eschews them in this decidedly vivid celebration of his life, covering his childhood and family background in St. Louis, with an afflicted sister, Rose, and redoubtably strong mother, who would inspire the characters in his 1945 breakthrough work “The Glass Menagerie.” There are some pencil-scribbled letters which, like most of his correspondence are deeply revealing on a personal level.

For me, the show piece of the exhibit is the portable typewriter he used throughout his life to send out so much thrillingly vivid communication to a world that often seemed either unready or too hostile to truly accept him for everything he adamantly insisted upon being. Seeing it stirred up thoughts of the sounds it must have made when its owner was in the eye of the storm of creativity, the clattering of the keys being tapped, the whir of the carriage return, and the tiny bell ringing. For him, the typewriter was a weapon, as well as a tool, with which to confront that world.

I was glad to see a beautiful portrait of Miriam Hopkins, the now little-remembered actress from Georgia, who was superior in my opinion to her more celebrated contemporaries, Bette Davis and Katharine Hepburn. She was one of fellow Southerner Williams’ earliest real patrons, as well as his first leading lady, starring in his playwriting debut, “Battle of Angels,” which closed after a disastrous two-week run in Boston in 1940. Actresses like her would inspire him all his life, and it was seeing the great Alla Nazimova on tour in Ibsen’s ‘Ghosts” that inspired Williams to become a playwright, just as he later inspired Tony Kushner.

Kushner, in an interview for the house publication of the Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, which has a huge Williams collection this show has drawn upon, said, “Williams, much more than any other American playwright, succeeded in finding a poetic diction for the stage. I immediately identified with that ambition, with the desire to write language that simultaneously sounded like spontaneous utterance but also had the voluptuousness in daring, peculiarity, quirkiness, and unapologetic imagistic density of poetry. Also because it is a written language, the tension between artifice, naturalism, and spontaneity in art has always been exciting to me. I felt that I experienced it really viscerally in terms of American playwriting first in Tennessee’s writing. As moved as I am by Tennessee’s clarity about sexuality and his refusal of the closet, I also think it’s very evident that he couldn’t write gay characters. As a result, we have Blanche DuBois, who’s a spectacular female character. But I’m sure it would’ve been salutary for him to write about gay men and gay women as well. Who knows, maybe he wouldn’t have been Tennessee Williams if he had had the freedom to do it. Trauma does produce extraordinary things.”

An early, signed incarnation of “The Glass Menagerie.” | COURTESY: MORGAN LIBRARY

The playwright embraced a peripatetic existence, fleeing trauma and boredom like his Princess Kosmonopolis in “Sweet Bird of Youth” — and didn’t the man come up with the best titles? — from hotel to hotel. Indeed, on display is a cache of hotel keys from all over the world the playwright had somehow forgotten to return at checkout time. But my favorite piece in this wonderful, do-not-miss show is a 1945 formal typed letter from one hotel manager who accused him of being “in the habit of doing considerable entertaining in your room,” adding that his establishment did not allow “entertaining in the rooms after twelve midnight.”

“‘That’s my Tennessee,” I chuckled to myself when I saw that, in total appreciation of a soul who absolutely lived life to the max, unhindered in his homosexuality even in a time and place where that could get you killed, and always going by the motto “Less is more, but more is more.” He was living proof of the truth expressed by reversing another hoary maxim, “The unlived life is not worth examining.” Happily, the Morgan Library, forever one of the real gems of our city, has decided to examine his, in the perfect setting and in the most wonderfully welcome and welcoming way.

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS: NO REFUGE BUT WRITING | Morgan Library, 225 Madison Ave. at 36th St. | Through May 13: Tue.-Thu., 10:30 a.m.-5 p.m.; Fri., 10:30 a.m.-9 p.m.; Sat., 10 a.m.-6 p.m.; Sun. 11 a.m.-6 p.m. | $20; $13 for seniors & students at morgan.org