“The girl with the long dreads lived in a house with a man, a Howard professor, who was married to a white woman. The Howard professor slept with men. His wife slept with women. And the two of them slept with each other. They had a little boy who must be off to college by now. ‘Faggot’ was a word I had employed all my life. And now here they were, The Cabal, The Coven, The Others, The Monsters, The Outsiders, The Faggots, The Dykes, dressed in their human clothes.”

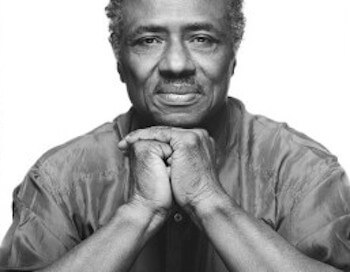

That passage appears roughly halfway through Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “Between the World and Me,” a brief, cogent, extremely potent book about what it means for a black man born in 1975 to come to manhood, realize himself, and emerge as arguably the most important African-American voice since James Baldwin, whose “The Fire Next Time” Coates’ book is to a large degree indebted to.

Baldwin, a forthrightly gay man at a time when it was highly “controversial” to be so, stood at the beating heart of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. He was personally acquainted with all its major figures, and they sought his counsel constantly, no matter how much of an “outsider” his sexual orientation made him to less-enlightened eyes. First published in the New Yorker magazine in 1962, and the following year expanded into a book, Baldwin’s most memorable nonfiction work dealt with the challenge Malcolm X’s militancy presented to a movement founded on “non-violence” as well as with the hard truths about how white racism was perpetuated. For Coates, born more than a decade after “Fire” and an idolizer of Malcolm X, these hard truths were simple realities.

James Baldwin’s successor articulates what it means to be a black man at a critical American moment

“Why were our heroes non-violent?” he asks, noting, “To be black in the Baltimore of my childhood was to be naked before the elements of the world, before all the guns, fists, knives, crack, rape, and disease.”

And that was just the start. Adulthood offered no respite or safe harbor.

“I am black and I have been plundered and I have lost my body,” Coates declares. “But perhaps too I had the capacity for plunder, maybe I would take another human’s body to confirm myself in a community. Perhaps I already had. Hate gives identity. The nigger, the fag the butch, illuminate the border, illuminate what we ostensibly are not, illuminate the Dream of being white, of Being a Man. We name the hated strangers and are thus confirmed in the tribe. But my tribe was shattering and reforming around me. I saw these people often because they were family to someone who I loved.”

And the someone who Coates loved was struck down precisely in the way Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Walter Scott, and Eric Garner were because, as he explains to the reader, “the police departments of your country have been endowed with the authority to destroy your body.”

Coates began writing about this and other matters of import in the Atlantic beginning in 2008 with an essay questioning the politics of Bill Cosby –– before it became utterly imperative to do so –– followed by others about an America that had supposedly become “post-racial” because Barack Obama was now president of the United States. Nothing, of course, could be further from the truth, and Coates is the ideal person to examine precisely why.

His father, William Paul Coates, was a Vietnam veteran and former Black Panther who founded and ran Black Classics Press. His mother Cheryl Waters-Hassan was a schoolteacher. It should also be pointed out that William Paul Coates had a total of seven children, five boys and two girls, by four different women, and was thus scarcely a “role model.” This was undoubtedly one of the reasons Ta-Nehisi Coates (an Egyptian name his father gave him that means “Nubia,” and in a loose translation “land of the black”) found so much happiness at Howard University and the world within it he calls “The Mecca.”

“The Mecca is a machine, crafted to capture and concentrate the dark energy of all African peoples and inject it directly into the student body. The Mecca derives its power from the heritage of Howard University, which in Jim Crow days enjoyed a near-monopoly on black talent… The history, the location, the alumni combined to create The Mecca — the crossroads of the black diaspora.” And it is at this crossroads that Coates comes to intellectual fruition — quite an achievement in light of his distrust of the education he had received up until then.

“When our elders presented school to us, they did not present it as a place of higher learning but as a means of escape from death and penal warehousing,” Coates declares in “Between the World and Me,” going so far as to state, “Schools did not reveal truths, they concealed them.” This clearly wasn’t the case at Howard, because truth was revealed at “The Mecca” as well as by the (never named) “girl with the dreads” who helped him through an illness and introduced him to her Bloomsbury-like extended family.

“The girl with the long dreads who changed me, whom I so wanted to love, she loved a boy about whom I think every day and about whom I expect to think every day for the rest of my life. I think sometimes that he was an invention and in some ways he is, because when the young are killed they are haloed by all that was possible, all that was plundered. But I know that I had love for this boy, Prince Jones, which is to say that I would side-eye whenever I saw him, for I felt the warmth when I was around him and was slightly sad when the time [came] for us to go.”

And there you have it. Ta-Nehisi Coates is not gay, but he knows more about what it means to be gay than most straights. And the reason for that is his willingness to speak of a man he could have loved. What prevented him from doing so was partially circumstantial (everyone went their separate ways after college) but decisively because that man was murdered by the police — an event that brought “Between The World and Me” into being and resonates throughout it. Prince Jones was killed by an undercover policeman in Northern Virginia. The cop had tracked Jones, whom he had supposedly thought to be a criminal suspect from Prince George County, Maryland, an area notorious for deadly police “encounters” with black men. As usual there was an “investigation,” which needless to say exonerated the officer thanks to his allegation that Jones had tried to run him over with his car. Observes Coates, “This investigation produced no information that would explain why Prince Jones would suddenly shift his ambitions from college to cop killing.” But it doesn’t have to. Jones was black and therefore a criminal suspect in the eyes of the law. The fact that the officer who killed him was also black shines a light on a species of “black-on-black crime” no one in our famously free press wishes to discuss. Coates says simply, “The officer who killed Prince Jones was black. The politicians who empowered this officer to kill were black.” Blackness in “defense” of the status quo, then, becomes the cynosure of racism’s full operational power.

For Coates, because of Prince Jones’ murder just the previous September, 9/11 wasn’t as compelling as it was for others. He was in New York when the World Trade Center was struck, but all he could think of was, “They sold our bodies down there”… indicating that the area was once a slave market. Bodies are of primary concern for Coates, especially that of his son, Samori Maceo-Paul Coates.

In an especially vivid passage he recalls an incident when, leaving a movie theater, a white matron shoved the boy roughly aside as she came down a stairwell. When he protested, a white patron yelled at Coates, “I could have you arrested!” Happily this violent rhetoric didn’t escalate into violent action because Coates stood his ground. But the message was clear. For daring to protest the authority of a white woman to do whatever she wanted with his son’s body, his own body could have been confiscated by the police.

“Between the World and Me” is dedicated to Coates’ son just as “The Fire Next Time” was dedicated to Baldwin’s nephew. Coates regards himself as just another black parent. “I think we would like to kill ourselves before seeing you killed in the streets that America made.”

It is to be dearly wished that that won’t happen — for Coates or anyone else. But American history only renders us foolish for daring to imagine this wish easily attainable. All we can do is find our “Mecca” and do everything in our power to make it grow –– regardless of the horrors that may be visited upon those we love by a system we hate.

BETWEEN THE WORLD AND ME |By Ta-Nehesi Coates | Spiegel & Grau | $24 | 176 pages