Chad Griffin, the president of the Human Rights Campaign, who as founder of the American Foundation for Equal Rights launched the Prop 8 litigation, seen with one of AFER’s lead attorneys, David Boies. | HRC

In a pair of 5-4 rulings released on June 26, the United States Supreme Court held that Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) violates the Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution, but that the court did not have jurisdiction to decide whether California’s Proposition 8 violates the 14th Amendment, because the initiative’s Official Proponents, who appealed District Court Judge Vaughn Walker’s decision finding it unconstitutional, lack federal constitutional standing to have done so.

There is a 25-day period during which the Official Proponents can seek rehearing, after which the high court’s mandate in the Prop 8 case will go to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which must then issue an order dismissing the appeal and lifting the stay on Walker’s 2010 ruling.

At that point, later in July or early in August, same-sex marriages could once again become available throughout California, though the Official Proponents may yet argue that Walker’s order does not apply to anyone other than the two plaintiff couples and thereby delay that outcome.

Legal same-sex marriages win federal recognition; California weddings will resume, but no broader ruling on right to marry

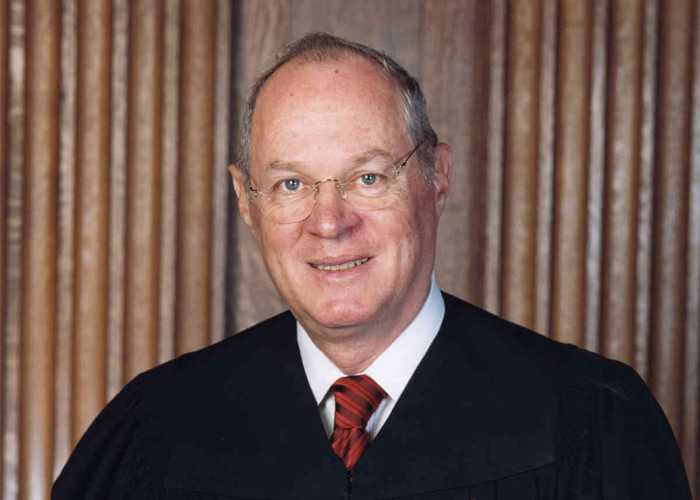

Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, Jr., wrote for the high court in the challenge that Edith (“Edie”) Schlain Windsor, a New York widow, brought against DOMA based on a $360,000 inheritance tax imposed on her after the death of her spouse, Thea Spyer. He produced a somewhat typical Kennedy opinion that obscures the ruling’s doctrinal basis and will leave commentators and lower courts guessing as to its effect in subsequent cases.

He referred to liberty protected by the US Constitution’s due process clause, federalism issues related to the traditional authority of the states to decide who can marry, and the equal protection requirements that the Court has found to be part of the Fifth Amendment’s due process clause.

In some respects, his opinion evoked his 1996 opinion for the court in Romer v. Evans, which struck down a Colorado voter amendment that prohibited any nondiscrimination laws based on sexual orientation in that state. Kennedy’s argument regarding DOMA rested on the idea that any enactment whose clear purpose and effect are to treat some people adversely, creating a sort of second-class citizenship, is unconstitutional on its face, without much need for further analysis.

At the March 27 oral arguments, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg described state marriage without federal benefits as “skim milk marriage.” Kennedy did not adopt that nomenclature, instead referring to second-class marriage.

As usual with Kennedy, his opinion avoids the technical terminology of constitutional analysis many commentators use in describing what standard of judicial review applies to the case, so it is not easy to classify it among categories including “strict scrutiny,” “heightened scrutiny,” “suspect classifications,” or “rational basis.”

The court, therefore, avoided settling the differences between standards applied by the trial court, which used the most deferential scrutiny in evaluating DOMA and found it lacks any defensible rational basis, and the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, which found that “heightened scrutiny” should apply to sexual orientation discrimination cases, a situation in which the government must show a compelling non-discriminatory purpose for a law. The appeals panel, while upholding Windsor’s trial court win, noted that DOMA’s Section 3 would survive a less demanding, more deferential rational basis review.

Kennedy's approach in this respect was at least a small disappointment for Windsor’s counsel, Roberta Kaplan of Paul, Weiss LLP, and the LGBT Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union, who had hoped that a “heightened scrutiny” ruling by the Supreme Court could be used in other cases, especially pending cases challenging state bans on same-sex marriage in other parts of the country. Claims of discrimination raised regarding laws subjected to heightened scrutiny are more difficult to defend against.

As usual when responding to a Kennedy gay rights opinion, Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissent expressed relief that the court had not used heightened scrutiny to strike down the 1996 law, but he then expressed puzzlement about its basis. After summarizing and criticizing Kennedy’s analysis, Scalia wrote, “Some might conclude that this loaf could have used a while longer in the oven. But that would be wrong; it is already overcooked. The most expert care in preparation cannot redeem a bad recipe. The sum of all the court’s non-specific hand-waving is that this law is invalid (maybe on equal-protection grounds, maybe on substantive-due-process grounds, and perhaps with some amorphous federalism component playing a role) because it is motivated by a ‘bare… desire to harm’ couples in same-sex marriages.”

Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan joined Kennedy’s decision and did not write separately.

Edie Windsor with her lead attorney, Roberta Kaplan, at the LGBT Community Center just hours after the DOMA ruling was handed down on June 26. | DONNA ACETO

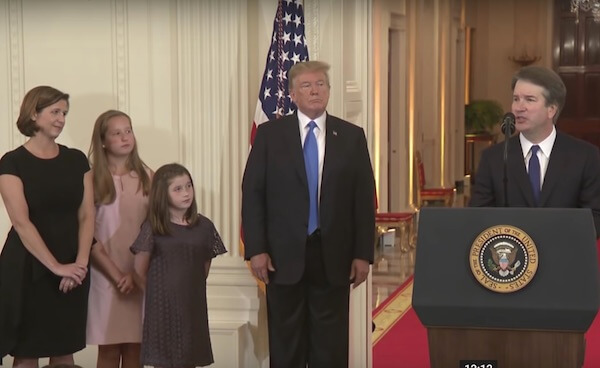

President Barack Obama promptly issued a statement applauding the court’s ruling and said he had directed Attorney General Eric Holder “to work with other members of my Cabinet to review all relevant federal statutes to ensure this decision, including its implications for federal benefits and obligations, is implemented swiftly and smoothly.”

In a press conference to discuss the Prop 8 ruling, Chad Griffin, the president of the Human Rights Campaign, said he had spoken to Holder “to discuss with him an expedited implementation of the DOMA ruling.”

This is especially good news for bi-national married same-sex couples, whose marriages can now be recognized as equal to those of different-sex couples, and it eliminates the need to amend the immigration reform legislation pending in Congress, something that even reform advocates who are marriage equality supporters, like New York Senator Chuck Schumer, have warned could derail that bill’s prospects.

Under the president’s directive, those federal statutes that contain specialized marriage definitions for particular policy purposes should now be construed to treat lawful same-sex marriages the same as lawful different-sex marriages.

However, as Scalia pointed out in his acerbic dissent, the court’s opinion is obscure on one very important question –– whether lawfully married same-sex couples who live, work, or travel in states that don’t recognize same-sex marriages will be recognized as married for federal purposes in such locations should the question arise. Kennedy ended his opinion with a cryptic statement, “This opinion and its holding are confined to those lawful marriages.” That sentence followed a passage criticizing DOMA because it “singles out a class of persons deemed by a State entitled to recognition and protection to enhance their own liberty” and has the effect of “disparag[ing] and injur[ing] those whom the State, by its marriage laws, sought to protect in personhood and dignity.”

This section of Kennedy’s opinion relies on principles of federalism, under which a state may, presumably, decide not to perform or recognize same-sex marriages unless, of course Kennedy’s due process and equal protection concerns would override that state’s reservations. That’s a question he does not resolve in his opinion.

There were three dissenting opinions. Scalia’s dissent was joined by Justice Clarence Thomas and, in part, by Chief Justice John Roberts, who wrote his own dissent as well. Justice Samuel Alito also wrote a dissent, which was joined in part by Thomas. Roberts and Scalia argued that the court did not have jurisdiction to decide the DOMA case, because the Justice Department, whose appeal was granted in this case, agreed with the rulings by the trial court and the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. Consequently, the parties before the court were not “adverse” on the merits and so lacked a true “case or controversy” as required by the Constitution. They both suggested that it was not appropriate for the government to ask the Supreme Court to affirm a lower court decision with which the government agrees.

The chief justice’s dissent stressed the “federalism” aspects of Kennedy’s opinion, a focus that could lessen its significance for pending challenges to state same-sex marriage bans. Roberts pointed to the fact that Kennedy’s opinion purported to take no position on the question whether same-sex couples have a right to marry under the 14th Amendment. He said “the disclaimer is a logical and necessary consequence of the argument that the majority has chosen to adopt. The dominant theme of the majority opinion is that the federal government’s intrusion in an area ‘central to state domestic relations law applicable to its residents and citizens’ is sufficiently ‘unusual’ to set off alarm bells. I think the majority goes off course, as I have said, but it is undeniable that its judgment is based on federalism.”

As such, Roberts would argue, it has no relevance to disputes over the basic question of whether same-sex couples have an underlying right to marry.

Roberts did not join the part of Scalia’s colorfully worded dissent where he disagreed with Kennedy on the merits of the case. Scalia discounted Kennedy’s disclaimer that the court was not deciding whether same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marry, predicting that lower courts would rely on his opinion to strike down state restrictions on same-sex marriage. In fact, Scalia took the unusual step of demonstrating how a lower court could appropriate paragraphs from Kennedy’s opinion, change a few of the words, and produce a result requiring a state to let same-sex couples marry. Scalia’s dissents in gay rights cases are usually packed with impassioned rhetoric, and this was no exception, but this is the first time he actually shows lower courts how to accomplish the terrible results he forecasts will occur. (Ten years ago to the day, in his dissent disagreeing with Kennedy’s opinion in the Lawrence case that struck down sodomy laws nationwide, Scalia warned that opinion would open the way for gay marriage.)

Alito, by contrast, argued in his dissent that the intervention of Speaker John Boehner’s so-called Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group of the House of Representatives (BLAG) –– which stepped in to defend DOMA when the Justice Department announced two years ago it would no longer do so –– took care of the “case or controversy” problem. He suggested there is necessarily a role for the courts to play when both the plaintiff and the government agree that a statute is unconstitutional. And he accepted BLAG’s contention that Congress has a legitimate interest in defending such a statute to protect its legislative authority.

Alito disagreed with Kennedy on the merits of the constitutional claim, asserting that whether the federal government must recognize same-sex marriages was a political question not suitable for resolution by the high court. Noting that the Constitution has nothing to say about same-sex marriage one way or the other, he argued the issue should be left to individual states to decide through their political processes.

Chief Justice Roberts wrote for the majority in the Prop 8 case, where he argued that amendment’s Official Proponents did not have standing to appeal Judge Walker’s ruling that it violated the 14th Amendment because they had no personal tangible stake in the outcome.

Scalia, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Kagan joined the court’s opinion. Kennedy wrote a dissent, joined by Thomas, Alito, and Sotomayor, in which he argued that the Official Proponents had standing and the case should be decided on the merits. Pundits will undoubtedly tie themselves in knots trying to figure out why three of the Democratic appointees joined Scalia and the chief justice in the majority while Sotomayor joined Kennedy and the court’s two most conservative members, Alito and Thomas, in the dissent, especially since the four Democratic appointees were united in joining Kennedy’s decision on the merits in the Windsor case.

Although the immediate results of both decisions are clear, their longer-term effects are not. The full meaning of a Supreme Court opinion cannot be determined on the day it is issued, but will depend on the responses of government officials, legislators, and lower courts, as well as private sector actors.

Section 3 of DOMA is gone, but that does not necessarily mean that all the barriers to full equality in federal rights are necessarily eliminated or will all disappear overnight. The president’s prompt statement and the comments HRC’s Griffin made about his conversations with the attorney general suggest that by the time the high court issues its mandate in the Windsor case toward the end of July, there should be some guidance from the Justice Department so that all federal agencies are on the same page concerning treatment of legally married same-sex couples.

It would be particularly helpful if this guidance addressed the issue of lawfully married couples who reside in states that don’t recognize same-sex marriages. The pending Respect for Marriage bill in Congress would mandate federal recognition for those marriages regardless of where the couple happens to live or be visiting, and the administration had stated support for that legislation. It is unlikely that Congress, politically fractured at present, would take any action were the administration to adopt this rule administratively.

Kennedy pointed out in his opinion that studies have identified more than 1,000 federal statutory or regulatory provisions for which marital status is relevant. Most of those provisions contain no express definition of marriage, while some include or refer to descriptive language relevant to the particular policy of the statute or regulation. Presumably, after the Windsor ruling goes into effect, any such provision that would not on its face include same-sex marriages would have to be interpreted consistently with the Supreme Court’s ruling to meet constitutional muster.

The court’s ruling on the Proposition 8 case is not a ruling on the merits of whether the California amendment is unconstitutional. Neither Roberts’ majority opinion nor Kennedy’s dissent takes any position on the merits of the equal protection theory adopted by the Ninth Circuit or the more sweeping equal protection and due process theories endorsed by Judge Walker in the trial court.

There are likely legal skirmishes yet to come in California. The original defendants in the lawsuit were the County Clerk’s Offices in Alameda and Los Angeles Counties, so they would clearly be bound by Walker’s Order. Whether clerks in other counties would be bound or would be subject to direction from state officials to comply is an unsettled question. Decisive action by Governor Jerry Brown may avert any chaos threatened by lawsuits contesting the scope of Walker’s ruling. Determined opponents of same-sex marriage, however, signaled immediately that they will do everything they can to try to block its implementation statewide.