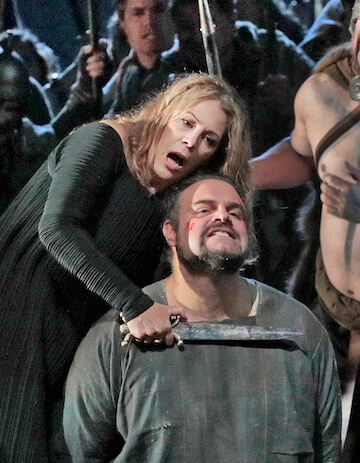

Javier Camarena and Diana Damrau in Bellini's “La Sonnambula.” | MARTY SOHL/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

Certain operas — Puccini’s “La Bohème” for example — can withstand non-star casting because the opera itself is the star. Less durable repertory items serve as vehicles for established stars with unique vocal qualities. Three star-dependent operas were revived this spring at the Metropolitan Opera. The casts were made up, with one notable exception, of familiar house singers and debuting artists. The artistic results varied widely but the box office suffered.

Diana Damrau’s star turn in a revival of Bellini’s “La Sonnambula” showed how a new cast can redirect a production from within. Damrau and debutant Javier Camarena not only delivered vocal brilliance but restored pathos and emotional truth to Mary Zimmermann’s production.

At the 2009 premiere, Natalie Dessay turned Amina’s dreamily ecstatic entrance aria “Come per me sereno… Sovra il sen” into a comedic skit about a ditsy, self-centered divette trying on shoes and silly wigs. Damrau recreated all of Dessay’s stage business but as a counterpoint to her rapturous expression of romantic love. Before launching into her sleepwalking solo aria, Damrau wrote “Elvino” instead of “Aria” on the blackboard, so the audience sighed rather than laughed.

Met offers “La Sonnambula,” “Andrea Chénier,” “Arabella” with mixed results

Damrau’s Amina is a hearty, outgoing creature with a full, womanly timbre rather than the delicate maidenly type with a floating ethereal timbre. Occasionally, trills and cadenzas were labored rather than quicksilver. In the “Ah! non giunge” finale, Damrau was the hardest working woman in show business. She led the corps de ballet in a jaunty ländler, was lifted overhead by the male dancers, tossed off Callas’ cadenzas and Sutherland’s staccati, executed a cartwheel, and brought down the curtain with an endless high E-flat.

Mexican tenor Camarena sang Elvino with a dulcet, honeyed, rich, and full-toned lyric voice that caressed Bellini’s arching vocal lines. Elvino was tender, modest, and charming but batted out high C’s and D’s in his Act II solos with divo bravura. (Handsome young American tenor Taylor Stayton sang Elvino on April 1 with a slender but sweetly soft-grained tone that opened up for bright high notes).

Michele Pertusi’s Count Rodolfo, despite indisposition, displayed the cantabile vocal line essential to bel canto. As the malicious Lisa, Rachelle Durkin’s raw, raucous upper register sounded as unpleasant as the character she portrayed, but she settled down to bright competence by the last show. Elizabeth Bishop exuded maternal warmth as Teresa.

Marco Armiliato’s uninspired conducting failed to imbue ensembles with rhythmic build and drive, so they ambled along aimlessly. In the solos, he catered to the singers who knew what they were doing.

Giordano’s “Andrea Chénier” is a Technicolor historical melodrama made for larger than life voices and personalities. The Met cast two mature lyric voices who have recently taken on heavier roles with variable success. Marcelo Álvarez sounded noticeably smoother as Chenier than as Radames or Manrico — he sang the initial phrases of his solos softly and lyrically, allowing room to build to moderately robust climaxes. Lyrical phrasing elicited his trademark honeyed tone, but when the going got tough his legato got choppy and pressurized.

Patricia Racette as Maddalena showed what five years of singing Tosca, among other spinto roles, can do to a silvery full lyric voice. She has lost her piano, and a widening vibrato seemed to push her forte high notes sharp and flat simultaneously. Racette built the dramatic arc of “La Mamma Morta” with canny insight, but her tone remained too bright and shallow. The climactic high B went awry.

Željko LuÄić’s hollow sounding Carlo Gerard tended to sag flat on sustained notes. But his rousing rendition of “Nemico della Patria” displayed the broadly expansive vocal canvas this music thrives on. Margaret Lattimore, Dwayne Croft, and especially debutante Olesya Petrova as Madelon provided strong supporting turns.

Gianandrea Noseda conducted with vivid color and energy — perhaps too much for his vocally underwhelming leads. The 1996 Nicolas Joël production is just a gilded picture frame showcase for star singers who stand and deliver. Not enough of the singing here delivered.

Strauss’ “Arabella” is an uneven period piece that requires a radiant soprano star like Lisa della Casa, Kiri Te Kanawa, or Renée Fleming to attract audiences. It was risky to offer rising Swedish soprano Malin Byström as the star attraction when her only previous Met appearances were a handful of Marguerites in a third cast of “Faust.” As Arabella, Byström’s rather brittle tone lacks the creamy warmth and silvery radiance of her predecessors — the top can turn stiff and her surprisingly dark middle lacks expansion.

Byström’s porcelain blonde beauty made a convincing belle of the Viennese ball, her cool, remote, and self-absorbed demeanor reminding me of Downton’s prickly Lady Mary Crawley. There was little romantic chemistry with her “Mr. Right” suitor Mandryka. (On April 24, Erin Wall sang Arabella with shining high notes and just the right mix of silver and cream. Less visually glamorous, Wall was infinitely warmer and more sympathetic, though just a touch more vivacity and volume were needed.)

The other leads were making Met debuts. Veteran German baritone Michael Volle won the audience over with his energetic, going at it hammer and tongs Mandryka. His jealous frenzy was the dramatic motor that drove the ramshackle plot contrivances of the second and third acts forward. Volle’s tone is sizeable but mature and dry-sounding, with a hint of Bayreuth bark on top.

Zdenka’s high agitated vocal line pushed Juliane Banse’s dark soprano into shrill edginess, marring the sisterly duets. Roberto Saccà delivered a musically and dramatically assured Matteo with a bleaty, unsympathetic tenor sound. Martin Winkler acted an amusingly louche Count Waldner, but Catherine Wyn-Rogers was a dowdy, colorless Adelaide. Audrey Luna’s coloratura Fiakermilli was all strident edge. As Count Elemer, Brian Jagde’s sunny tenor and smiling countenance lit up the stage.

Philippe Auguin’s swift, no-nonsense conducting invested the many less than purple pages of Strauss’ score with animation and energy. This is one opera that resists modernization, Otto Schenk’s representational period-specific production creates a handsome but slightly grimy around the edges view of 1860s Vienna.