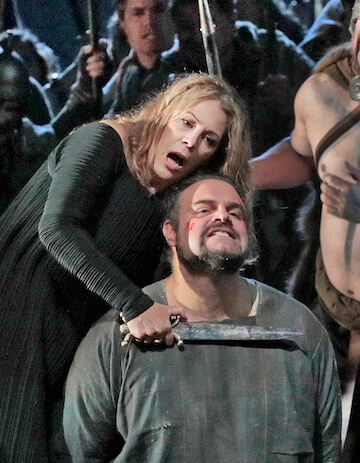

Jonas Kaufmann sings Tristan in concert with Boston Symphony led by Andris Nelsons. | CHRIS LEE

On April 12, anyone close to Manhattan who considers themself a hard-core opera fan was in one place: Carnegie Hall. We were all convened in that hallowed hall to hear Jonas Kaufmann attempt his first partial climb up the Mount Everest that is Wagner’s Tristan in a concert performance of Act II of “Tristan und Isolde” with the Boston Symphony Orchestra led by Andris Nelsons.

Nelsons’ interpretation of the score is much more sensual and warmly emotional than Simon Rattle’s coolly cerebral, clinical take at the Metropolitan Opera two seasons ago. The strings and woodwinds rustled with fevered expectation and then floated hypnotically into the night air — the spell only broken by some out of tune horns offstage representing King Marke’s hunting party (which really does break the spell later on in the act when the King stumbles upon his wife and best friend’s tryst). Nelsons could have been more impulsive in his rhythmic attack but this was a measured, authoritative reading and his Boston players acquitted themselves well.

As Isolde, Finnish soprano Camilla Nylund was more of a jugendlich heldensopran (lyric-dramatic) than a hochdramatisch (heroic Wagnerian dramatic soprano). A noted Elsa and Elisabeth who will debut in a few seasons at the Met as Strauss’ Marschallin, Nylund was initially overparted by the “Frau Minne” section. She needed extra mid-phrase breaths to get through the overwhelming outburst where Isolde extinguishes the torch. However, once Kaufmann’s Tristan came on the scene, Isolde’s music becomes more lyrical and here Nylund was more in her natural element. Her voice is a good instrument and she is a striking statuesque blonde — but I say the complete role should be taken on by her in about 10 years and only in small houses.

Jonas Kaufmann takes on Tristan; Met revives Laurent Pelly “Cendrillon” production; “L’amore dei tre Re” from NYCO

Veteran Bayreuth mezzo-soprano Mihoko Fujimura sang Brangäne with focused intent and authority; her tone is even and concentrated and her German diction is clear. Bass Georg Zeppenfeld brought a lieder singer’s subtle attention to detail and line to King Marke’s long monologue. Zeppenfeld’s tone is that of a true bass and this Marke remained dignified and regal, never stooping to self-pity or bathos.

And what of our errant tenor? Kaufmann’s curly locks are now sprinkled with salt and pepper and his waist is not as slender as it once was — but then neither is his voice. His handsome baritonal tenor seemed in healthy but somewhat blunted condition — the tone is very covered and dark with not enough light to offset the tonal shade. The “Tag” or “Day” section was sung with stentorian force and Kaufmann’s face turned red with the heroic effort — but the tone remained steady with unforced power.

In the dreamy “O sink hernieder” “Liebesnacht” section, Kaufmann attempted to soften the tone but his voice lacked float. One longed for a shaft of pure bright tenor tone suggesting tenderness and longing to offset the opaque covered sounds.

Jon Vickers managed to survive Tristan successfully for decades not by deploying extra vocal muscle but by exploiting every “piano” and “mezza voce” marking in the score. Vickers’ third act Tristan was practically a full-evening Frankie Valli solo concert of falsetto crooning. If he is to successfully attempt the entire role, Kaufmann needs to cultivate the lieder singer lyricism and lightness in Tristan’s eternal night. His reading of Schubert’s “Die schöne Müllerin” at Carnegie Hall this past January showed the potential that is there.

Opera obsessives allergic to Wagner had another option on April 12: the belated Metropolitan Opera premiere of Jules Massenet’s 1899 fairy tale opera “Cendrillon” (“Cinderella”) with a libretto by Henri Caïn adapted from the Perrault. Cinderella and her Prince Charmant, like Tristan and Isolde, are lovers separated by society who resort to magic. In Act III of Massenet’s charming “Cendrillon,” our heroine Lucette has her own nocturnal episode in a forest glade where she and her royal lover, magically reunited by the Fairy Godmother, are longing for death yet craving the love that cannot be consummated in their daily life.

Massenet’s “Cendrillon” was imported by the Met as a vehicle for the popular Yankee diva mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato. The occasionally overly whimsical yet endlessly witty and imaginative production by Laurent Pelly was created for Santa Fe Opera back in 2006 (starring DiDonato) then traveled to Covent Garden, Barcelona, and Brussels. Pelly recreated his production at the Met with style and flair and it looked none the worse for wear given its age and travels. Pelly’s costumes are hilarious and absurd — check out the procession of prospective brides in the Act II ball scene. Barbara de Limburg’s quick-moving scenery consists of rotating white walls with Perrault’s “Cendrillon” text written upon them as if a book of fairy tales has come to life.

Alas, neither our Cinderella nor her Prince proved as untouched by the passage of time as Pelly’s staging. Massenet strives to create a world of childlike innocence but DiDonato as Lucette is 49 years old and Alice Coote in the trouser role of Prince Charmant will turn 50 the day before the last performance on May 11. Both are singing roles composed for a soprano and their voices now strain at the high notes and tessitura. DiDonato’s tone too often turned white with rattling vibrato while Coote let out some raw high notes with puffy matronly tones below. Looking more like a sophisticated woman of the world than a radiant ingénue in her white sleeveless ball gown, DiDonato does project sincerity and her soft middle register singing has a mournful delicacy.

Both mezzos are fine musicians and committed actors with stylish phrasing and sensitive projection of Caïn’s text. But they have both outgrown these parts that would be better served — perhaps in a projected revival? — by Nadine Sierra as Lucette with Marianne Crebassa as her Prince (and add coloratura Sabine Devieilhe to the mix for her Met debut as La Fée).

The Met showed greater imagination and aptitude in casting the supporting roles: Kathleen Kim sparkled as La Fée sprinkling incandescent high D’s over the stage like glittering fairy dust while her legato tone was buttery and sweet. Stephanie Blythe as the imperious stepmother Madame de la Haltière had a field day reveling in a booming contralto, ridiculous wigs and hilarious over-the-top reactions. Laurent Naouri as Cendrillon’s ineffectual yet loving father Pandolfe brought wittily precise acting and diction to the part enlivening each moment. The stepsisters Noémie and Dorothée work more as an ensemble team than as individualized personalities: Ying Fang and Maya Lahyani were as elegant in their vocal harmony as they were absurdly awkward in their physical impersonations. The supporting players and chorus precisely executed absurd comic business and even dance the choreography of Laura Scozzi.

Bertrand de Billy in the pit expertly evoked the 18th century rococo elegance that Massenet interwove with the more romantic passages. Massenet spiked his “Cendrillon” score with a coolly droll modernism that Francis Poulenc would mine 25 years later. Despite the miscast leads, the “Cendrillon” of Massenet & Pelly & Co. is a musical and visual delight that will enchant the proverbial children of all ages.

Jules Massenet and Italo Montemezzi were both accused of Wagnerian tendencies by their contemporaries: Massenet was dubbed “Mademoiselle Wagner” by sneering critics. In “L’amore dei tre Re” (1913), Italo Montemezzi sets Sem Benelli’s florid symbolist libretto to a lush score that mixes verismo melodrama with Debussy’s shifting harmonies and Wagner’s freewheeling chromatic “Tristan” chords. Once a highly admired repertory staple, after World War II Montemezzi’s masterpiece became an obscure curiosity — it is rarely staged even in Italy.

New York City Opera revived the work for four performances April 12-15 borrowing a handsome physical production of carved stone medieval castle ramparts (designed by David P. Gordon) from the Sarasota Opera with contrasting World War II era costumes (by Janet O’Neill). Michael Capasso’s production concept seemed to suggest that the invading conquerors Archibaldo and his son Manfredo are World War II fascists or even Nazi invaders while Fiora and her former fiancé Avito are secret members of the Italian resistance. The updating didn’t add much and didn’t take much away — the evocation of 1940s Italian cinema of De Sica was an interesting idea that wasn’t developed in a compelling way.

The male casting was strong: Veteran supporting bass Philip Cokorinos emerged a star player as the blind King Archibaldo singing the role with vibrant and compelling depth. Cokorinos acted the part with chilling intensity finding hints of tortured humanity beneath the tyrant’s suspicious and sadistically controlling nature. South Korean baritone Joo Won Kang poured out a rich, smoothly powerful Verdian baritone as Manfredo but lacked Cokorino’s stage presence and intensity. Giuseppe Varano as Fiora’s lover Avito revealed a richly colored, stylistically apt tenor that remained attractive until pushed for stentorian power — then some leathery sounds emerged.

As Fiora the alluring object of their desires, Italian spinto-dramatic soprano Daria Masiero looked overripe and sounded worn and scrappy. An Anna Magnani type fits the updated mid-20th century setting but not the character who is supposed to be sensual yet mysterious and aristocratic.

Pacien Mazzagatti conducted an excellent pick-up orchestra with controlled passion and idiomatic flair while the supporting singers and chorus featured fresh well-trained voices. The entire production showed thorough rehearsal and commitment to the piece. Benelli’s decadent melodramatic libretto with its florid poetics may be what is keeping Montemezzi’s score off the stage.