It was another late after-school night, hours after the last period bell had rung, and I was alone, surrounded by black and white pictures of other boys’ butts. They were strewn across my desk, and I was trying to figure out which were the best among them, and where to position them. All before deadline.

It was another late after-school night, hours after the last period bell had rung, and I was alone, surrounded by black and white pictures of other boys’ butts. They were strewn across my desk, and I was trying to figure out which were the best among them, and where to position them. All before deadline.

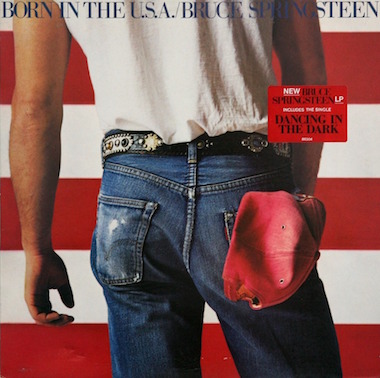

I wasn’t clandestinely putting together some gay teen soft-porn magazine. You see, I was the yearbook editor – technically, co-editor, among three of us. This was 1986, long before the Internet, “Pretty in Pink” and other Brat Pack movies the touchstones for my generation. It was also the height of Bruce Springsteen’s worldwide fame, the era of “Born in the USA.” And if you remember anything about that iconic album cover, it was all about Bruce’s butt, clad in a pair of Levi’s, a red baseball cap emerging out of his back right pocket, the red and white stripes of an American flag in the background.

I was alone with these photographed posteriors in the most special place in all the world to me at the time: Freehold, New Jersey, inside of Bruce Springsteen’s high school, a view out the window to the now darkened courtyard where long before he was famous, he played his guitar to the annoyance of our same teachers who swore he was a failure who would never make anything of himself. His new autobiography, “Born to Run,” is the latest proof of how wrong those teachers were.

These other boys’ butt images were a tribute I was putting together for The Boss, a man who was quite literally “My Hometown” hero.

Learning the joys of journalism editing the yearbook at Bruce’s Jersey high school

We were recreating the famous album cover throughout the 1986 yearbook, The Log, with butts as end notes and dividers, along with other Bruce-themed concepts. It wasn’t my idea, I have to admit, but it became my job to execute the plan as part of a committee, finding male classmates with the best butts, having them photographed, and deciding how to use the images.

I was – mind you – adamantly against the Bruce Springsteen theme, thinking it a Freehold cliché we should escape from. I wanted some kind of newspaper concept, allowing us to do mini-articles throughout its pages. Our advisor had the idea, hoping, as I remember it, that if we sent Bruce the yearbook, he’d be so flattered at the gesture he’d give a concert at the high school as a way of saying thank you.

Painfully, I have to admit I had another problem with this theme, one with a certain irony. Being a deeply closeted gay teenage boy at the time, I feared having to make decisions about the butts of my classmates. What if they thought I was too gung-ho about their butts, expressing way too much of an interest in what I was doing, or if I lingered too long over the images? Or if I blurted ahead of time which of the boys in class I already thought had great butts, because I’d been staring at them long before the “Born in the USA” album jacket brought Bruce’s Freehold fanny to fame? At least I could take solace in the fact it was not my idea, and I’d voiced my opposition.

It seems odd, but I didn’t really need to worry about how other boys’ butts were a strong interest of mine. Turns out there had long been consensus about which boys had the best butts, even among our male teachers advising us.

Beyond feigning a lack of interest as I went through image after image, being yearbook editor taught me how to hide yet be out in other ways. For one, I learned no one picks on or beats up the yearbook editor, because no one wants his or her picture “accidentally” not in the yearbook.

Most people who know me now refuse to believe I was shy in high school, but it’s true. Being editor helped draw me out of my shell. Or at least taught me how to move around inside of that shell. I learned how to hide myself and be everywhere, even in social places I wouldn’t normally feel comfortable in, surrounded by jocks and popular kids. But with a camera and a notepad as shields, I had complete freedom. I was another person. Journalism, covering the news, being at events –– many of which I created as part of the yearbook, homecoming, prom, and other committees –– meant I belonged everywhere at school, no matter how socially awkward I felt.

Looking back, no other place could have done what we did with a Bruce Springsteen yearbook theme. Other schools might love Bruce, but none had our geographic cred.

Michael Luongo. | MARK BENNINGTON

Freehold, top of the Jersey Shore, minutes inland from Asbury Park, where Bruce rose to fame, is on the edge of New York City’s suburban ring, its remaining farms sprouting McMansions at the time. Site of the American Revolution’s pivotal Battle of Monmouth, its legends told of a mass grave in the center of town and of female revolutionary warrior Molly Pitcher, grounding us in history and showing us American feminism was a virtue born in our town. Still the historic core struggled to overcome the Main Street decay of “white washed windows and vacant stores” that Bruce sang of. In reality, there were two Freeholds: the wealthy white ethnic suburban one where I lived, and the downtown one, racially mixed and economically troubled, where Bruce’s and my 1920s high school, designed based o Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, was located.

It was there that I learned what Bruce Springsteen values are, the themes in his songs, which made me who I am today. Values resonating in our presidential election: the struggles between those who have and those who don’t, tossed from the American Dream by worldwide economic dislocations. No American artist gets the problems of the working class like Bruce Springsteen, and in mid-‘80s Freehold, with songs about the streets and places you saw every day memorialized on the radio, it was impossible to grow up without understanding these social issues –– and, today, having those issues continue to shape you.

Though he referred to 1960s tensions, saying, “There was a lot of fights between the black and white. There was nothing you could do,” we knew as 1980s high school kids there was something we could do. We resolved racial differences through dance parties mixing so-called white and so-called black music, and breakdancing competitions during that fad’s height of popularity. I’ve even kept the spray-painted urban graffiti backdrop we created for those competitions that everyone –– white, black, Latino, and Asian –– participated in.

There’s another line in “My Hometown,” with strong resonance in this political season, about globalization’s impact on the American worker. “They're closing down the textile mill across the railroad tracks. Foreman says these jobs are going boys and they ain't coming back.” Bruce is singing of the Karagheusian Rug Mill, a factory which once employed hundreds of people, opened at the turn of the last century by an Armenian refugee who had fled the collapsing Ottoman Empire. I might have been raised middle class, spoiled by some measures, but when you sit next to people in high school homeroom who grew up poor, some of whom might not have eaten that morning, children of families laid off years before by the mill Bruce sings about, it’s impossible not to develop a concern for the working class, one that has followed me throughout life. Even now, living in Michigan, down the road from blighted Detroit, it’s hard not to think of Bruce when listening to Rust Belt struggle stories.

By the early 1990s, I would learn that beyond working class and racial issues, Bruce Springsteen also cared about issues for people like me, gay men, when he recorded the song “Streets of Philadelphia” for the 1993 film “Philadelphia,” in which Tom Hanks played a gay man dying of AIDS. Springsteen would appear in 1996 on the cover of the Advocate. More recently, he spoke out against the North Carolina bathroom bill, cancelling a concert there in protest.

It was an amazing revelation to me that LGBT values were Bruce values, that the most famous person from my high school was speaking out for LGBT equality. Maybe he would have gotten a kick out of a closeted gay teenager poring over photos of other boys’ butts to build a memorial to his fame. Yet looking back, and knowing the gay history of where Bruce became famous, Asbury Park, he likely had long socialized among gay people in the creative seaside town.

The New York Times might proclaim the town’s gay popularity as a recent phenomenon, but this is a public relations fantasy. The town once rivaled Provincetown and Fire Island. No one was gayer than sassy “Hollywood Squares” center square Paul Lynde, who made Asbury his favorite resort, staying at the now demolished Metropolitan Hotel, according to officials from the city I interviewed in the early 1990s, when there was a short-lived plan to convert the abandoned Steinbach’s department store building into a gay shopping mall complex. From an early age, long before he was famous, and certainly well before it was mainstream, Springsteen probably incorporated LGBT values from among the spectrum of social issues he absorbed from the Jersey Shore’s dying towns.

In the end, we never did get that Springsteen concert, but we did get a nice letter from him. And of course, Freehold had plenty of Bruce sightings back then, as it still does today. I never personally met Bruce Springsteen, though I have long wanted to interview him, a natural subject for me as a fellow high school alumnus.

Thirty years on from the first major editorial project I was ever in charge of, I’ve learned a lot. Editing the Freehold High School yearbook changed my life by teaching me the things that journalism could give me in life in helping me break me out of my own head. Who knew a lonely, closeted high school kid could parlay editing a Bruce Springsteen-themed yearbook, looking at pictures of other boys’ butts late at night to meet a deadline, into a journalism and editing career decades down the road?

We may all just be that annoying person in the high school courtyard our teachers think will never make something of ourselves, but you never know where life, Bruce Springsteen values, and photos of other boys’ butts will take you.