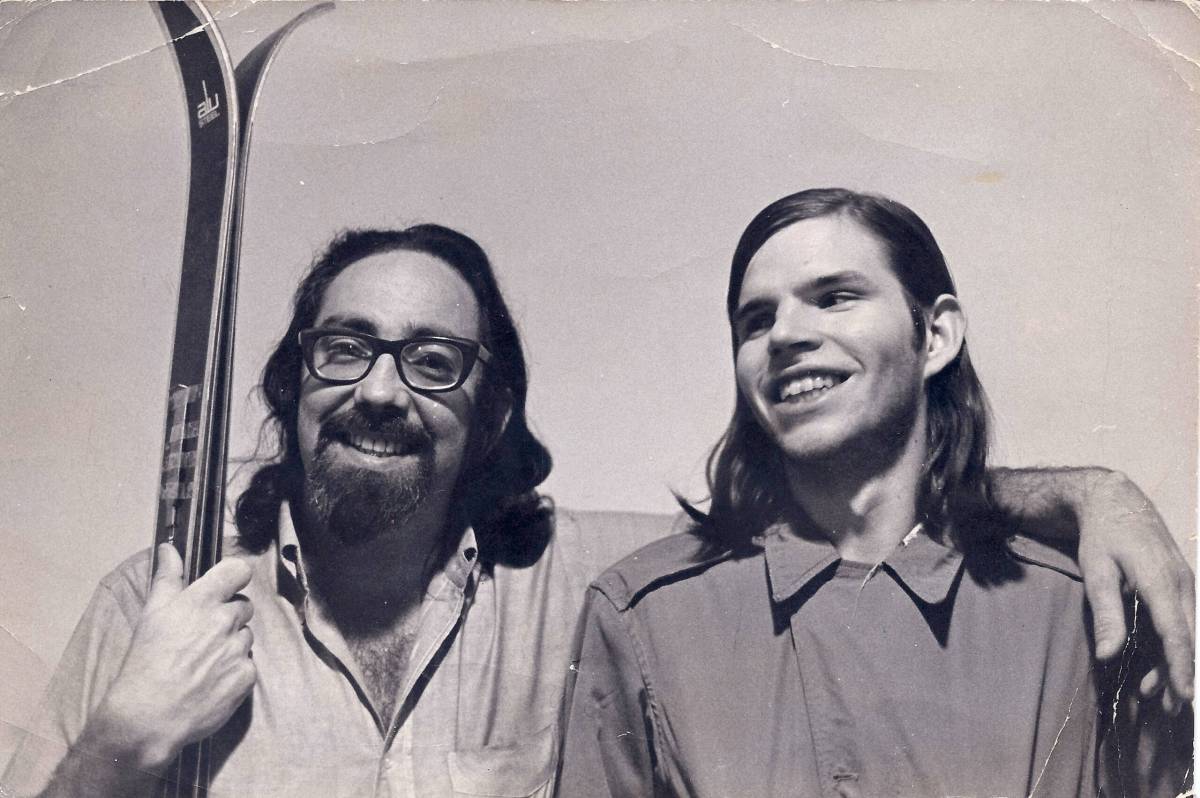

NOTE: Pioneering gay therapist and activist Dr. Charles Silverstein, who died at age 87 on January 30, shared this account of his involvement in the historic campaign to get the American Psychiatric Association (APA) to take homosexuality out of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual as a mental illness in the early 1970s. It is published with permission of his estate. It is an invaluable first-person account of the most important turning point in the early gay movement since Stonewall.

The following story is from the point of view of New York City’s contribution to the removal of homosexuality as a mental illness. While accurate, it is not the only link in that chain of events. Activists in other cities made a significant contribution as well, but contemporary witnesses to them will have to tell their side of the story. Communication between gay activists throughout the country was poor in those days for many reasons: the expensive use of telephones, copies of meetings were reproduced with onion skin and carbon paper, and the philosophical differences between geographical regions about the proper strategy for confronting the psychiatric establishment.

In the 1970s, New York’s Gay Activist Alliance (GAA) was the leading radical gay organization. A year or two earlier, the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) had been the most vocal organization and they had sponsored the first Gay Liberation March (not parade) in the city. But GLF broke up rather quickly due to internecine warfare about their goals. GAA replaced them and devoted itself to fight only for gay rights.

I was a graduate student at the time. I was also a member of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy (AABT), now called the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy. I had joined with the express purpose of challenging the use of aversion therapy on gay people. I knew that we had many allies there, more so than one could find in any other psychological or psychoanalytic association. I joined so as to make an alliance with them against what I considered to be torture against gay people.

AABT was having their annual convention at New York’s Hilton Hotel on October 8th, 1972. Two or three practitioners of aversion therapy were scheduled to present papers at the convention. I asked the executive board of GAA to “zap” the convention. They enthusiastically voted to do so. The psychiatric profession was considered to be a “gatekeeper” of social attitudes, and we were convinced that if we could remove the stigma of homosexuality in medicine, that sodomy laws would eventually fall, and that gay people could make a significant advance toward gaining our civil rights. Since I had the program for the convention, I knew which meetings we could choose in which to hold our demonstration. The decision was based upon the advice of our PR committee. A public demonstration is of little value if no one hears about it, so we always sent press releases to the newspapers in advance of our demonstrations. Beside the publicity, having the press was reassuring to us because without it the police were wont to beat the hell out of us, sometimes seriously.

That problem worried me. The security guards at the Hilton Hotel had a reputation for overreacting during demonstrations. The year before, at a meeting of the “Inner Circle,” an annual meeting of power brokers in the city, Morty Manford and Jim Owles had been beaten up at the Hilton by Michael May, president of the Fireman’s Union, in front of police (including the police commissioner). The activists were arrested, but May was not. I did not want to see anyone hurt during our demonstration — particularly me. (We were advocates, not masochists).

The PR committee decided to “zap” an aversion therapy lecture by a psychiatrist named Quinn (I can’t remember his first name). His lecture was perfectly timed for us to do our work, and to allow the newspapers the opportunity to photograph the demonstration outside the Hilton and to get the story into the papers for the next day.

I asked a few AABT officers to meet me at Quinn’s workshop. When they arrived, I explained what we were going to do. They promised to keep the security guards at bay, and they kept their promise.

About a dozen of us walked into the room and sat down. We were spotted immediately by the Hilton security people who then called other guards to join them but AABT officials prevented them from coming into the room.

The next problem was Dr. Quinn. I decided that he should know what was going to happen and I wanted him to acquiesce to our breaking up his lecture. That was a cinch. Professionals (including us) are not brave people. They generally fold under the slightest pressure. I walked up to him and in a quiet but firm voice said something like, “Dr. Quinn, the room is filled with radical gay liberationists and we are here to fight against aversion therapy used against our people. You can talk for 15 minutes, then we’re going to take over the room and tell the audience how gay people are being tortured. You don’t have to worry, no one is going to physically attack you or anyone else.” I ended by saying,” Dr. Quinn – it’s going to happen anyway, so I suggest you cooperate, give your talk, then we take over, and you can listen to us.”

He caved in immediately. I particularly used the word “radical,” so as to intimidate him. I thanked him for his cooperation, and sat down. The word “radical” is terrifying to most professionals and when used correctly results in almost complete capitulation. But this only when said softly and firmly. It is far less effective when yelled accompanied with menacing gestures. In that case, the opposition identifies you as irrational and a bit of a lunatic. But the “soft” radical carries a meta-message of being more in control, hence more menacing. Telegraphing your punch as I did with Quinn, is another effective technique when working with professional groups who are conservative by nature, and will do virtually anything to prevent trouble. One need only be polite, respectful, firm, and to let the person know what you’re going to do – and what’s expected of him.

Quinn walked to the front of the room, I walked to my seat, and the AABT officers stood guard at the door. After Quinn talked for 15 minutes, Ron Gold from GAA stood. “You’ve talked long enough, Dr. Quinn,” said Gold. “Now it’s our turn.”

We chastised the professional audience for their attempts to convert homosexuals into heterosexuals instead of helping gay people to come out. The audience erupted into fury. Many of them were also opposed to the use of aversion therapy, but they were angry at our interruption of their meeting. For the next hour, the two groups exchanged ideas; by the end of the meeting, many people felt that it had been a useful exchange.

In the audience was Robert Spitzer, a research psychiatrist and a member of the Nomenclature Committee of the American Psychiatric Association, the committee that formulates and makes changes in the DSM diagnostic system. Spitzer suggested that gay activists take their complaint to the Nomenclature Committee.

An ad hoc committee of gay activists, mostly from GAA, was formed to organize the presentation. They were instructed, however, not to identify themselves as an official GAA committee, simply as a group of interested individuals because GAA did not want to be seen as cooperating with the psychiatrists. (While this may seem strange to the modern reader, the fear of a radical gay rights group being coopted by a mainstream institution such as the American Psychiatric Association was the motivation for denying GAA’s control of the committee.) The committee consisted of chairman Ron Gold, Jean O’Leary, Rose Jordan, Ray Prada, Brad Wilson, Bernice Goodman, and myself. An excellent preparatory written report citing recent psychological research on homosexuality was prepared by Wilson and Jordan, and sent to the psychiatric Nomenclature Committee.

Our committee, ruled with an iron hand by Ron Gold, elected to make two presentations at the meeting with the psychiatrists. Jean O’Leary, an ex-nun, was assigned the first of these, a presentation about the harmful effects of pejorative labeling on gay people in their struggle for civil rights. I was asked to discuss the diagnosis of homosexuality from a professional point of view.

We met often. Each member was assigned the responsibility of fielding potential questions from the psychiatrists. Jean and I were asked to read our presentations aloud in order for other members to critique them. At each of these meetings, I reported that I had not yet finished mine. This was met by displeasure, particularly by Gold, who insisted that my presentation be sufficiently militant and confronting. But I did not want to play the role of a gay activist with the Nomenclature Committee. I knew they’d be expecting that, and I wanted to find a more effective strategy. The last thing I wanted to do was to write something for the ad hoc committee’s approval. I had no intentions of reading anything to them before the meeting with the psychiatrists. Only Bernice Goodman knew what I was doing.

I decided to spend my time reading about all the diagnostic systems that had ever been invented to classify human behavior, to understand their structure as social documents reflecting the worries of their times. I began to see these systems as a means of identifying people whose behavior was inexplicable, therefore feared, and, for that reason, condemned.

It was not possible to read this material without chuckling. Most of the diagnostic categories consisted of socially disapproved behavior. Examples in the DSM from 1968 included lying, stealing, the fear of getting syphilis, or simply being a cranky person.

The presentation to the Nomenclature Committee was scheduled for February 8th 1973. I wrote it the evening before, while sitting at my desk pounding away on my old typewriter, and practicing it verbally for my lover, William.

The committee received us cordially. They had all read our written report, and they were prepared to listen to what we had to say. Jean and I presented our statements to the Nomenclature Committee at Columbia University’s Psychiatric Institute. The first part of my presentation highlighted the humor one can find within the pages of diagnostic systems. I then tried to demonstrate that the only foundation for the classification of a “Sexual Deviation” was moral, not scientific. (This may seem obvious today, but it was a radical idea in many professional quarters at the time.) I chastised the committee for the role that the psychiatric profession played in the disenfranchisement of, discrimination against, and legal penalties suffered by gay people because we had been diagnosed as psychopathic and sexually deviant. I ended my presentation with the exhortation: “To continue to classify homosexuality as a disorder is as valid today as was the diagnosis of masturbation in the 1942 edition. What we hope to convey to you is that we have paid the price for your past mistake. Don’t make it again.”

During lunch, Henry Brill, the committee chair, mentioned some of the impediments to removing homosexuality as a mental disorder from the DSM. The psychoanalysts formed the biggest roadblock. Psychoanalysts were adamant in their belief that homosexual behavior was aberrant and doomed a gay person to a life of loneliness, depression, and ultimately suicide. Only psychoanalysis could save the homosexual from himself, said Charles Socarides, the most pompous of the analysts. In 1965, Socarides wanted the federal government to set up a Center for Sexual Medical Rehabilitation, a concentration camp for faggots. Even other psychiatrists were shocked at the idea, and his suggestion was ignored. During lunch, Brill and I talked about the opposing analysts, and gossiped about famous gay psychoanalysts such as Anna Freud and Harry Stack Sullivan. He was shocked at my estimate that between 10 – 20% of his colleagues were gay.

The Nomenclature Committee, even though divided, voted to recommend the removal of homosexuality as a mental disorder in the next edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. Their recommendation, however, had to be approved by the Board of Trustees of the American Psychiatric Association. In March, Richard Pillard, a gay Bostonian psychiatrist and an active supporter of the removal of homosexuality as a mental illness, convinced the Northeastern New England District Branch to endorse the nomenclature change, making them the first affiliate of the American Psychiatric Association to do so. This was an important step, since it demonstrated that local associations would support the recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee.

I was not privy to the board’s discussions, but my understanding from those who were — and from Ron Bayer’s authoritative account, “Homosexuality and American Psychiatry” — is the following. Most members of the board were sympathetic to the Nomenclature Committee’s request, but the removal of homosexuality as a mental disorder represented conflicting moral, ethical, political, and economic values for the board. There was sympathy for the fact that gay people had been discriminated against in our society, and acknowledgment that the medical/psychological profession had contributed to that sorry state of affairs. But psychoanalytically oriented psychiatrists had built their reputations on curing homosexuals, and an affirmative vote by the board would represent a slap across their professional faces. It would also have an economic effect upon these and other psychoanalysts, since many gay men would no longer seek treatment in order to change their sexual orientation. The APA Board of Trustees was now forced to face that problem, and they feared a rebellion by the psychoanalytic members of the association, who were raising petitions against the proposed change.

The Board of Trustees tried to mollify both sides of the conflict. The suggested compromise asserted that some homosexuals are happy with their lives and have no wish to change their sexual orientation. These homosexuals were called “ego syntonic” and, therefore, not in need of psychiatric treatment. On the other hand, there were homosexuals who were “ego dystonic,” unhappy with their sexual orientation, and appropriate for treatment. The board removed homosexuality from the list of sexual deviations, and replaced it with “Ego Dystonic” Homosexuality by a vote of 13 for, none against, and two abstentions.

The next day, in New York City, was the annual meeting of the American Psychoanalytic Association. Charles Socarides, infuriated at the APA action, arrived with a petition demanding that the complete APA membership vote on the diagnostic change. Socarides secured 200 names to his petition, enough to force a vote.

Gay activists knew that a referendum of the APA membership might overturn the nomenclature change. The psychoanalytic group, led by Socarides and Harold Voth, sent out a letter to the membership challenging the board decision, claiming that the association was being taken over by gay activists. To counter this letter, another, written by Robert Spitzer and Ron Gold, was mailed out. It was paid for by money raised by The National Gay Task Force, a new gay liberation group that had been organized by Gold and Bruce Voeller after they left GAA.

The Gold/Spitzer letter cleverly argued that a professional organization should support the actions of its Board of Trustees. The letter cited many examples of civil rights violations against gay people that had been justified by the misuse of psychiatric diagnosis. The mental status of homosexuality was left in the background since we were under no illusions about the conservative nature of most psychiatrists in the country. Many prominent psychiatrists signed the letter, including the sitting president of (their) APA and all the future candidates for president. The letter did not reveal that it was paid for by a gay activist organization.

Socarides and his rat pack howled when they learned about the letter. They publicly accused APA officers of fraud, and demanded an internal investigation, which could not have endeared them in the eyes of these officials. Charles Socarides had a bull-in-a-china shop approach to conflict, and his abrasive style turned off many other psychiatrists. We were, therefore, grateful to have him lead the charge against us. The subsequent investigation repudiated the accusers.

About ten thousand psychiatrists voted in the referendum. Fifty-eight percent supported the actions of the board, while thirty-seven percent voted against. A few years later, due to the lobbying of a number of psychiatrists, particularly Richard Pillard in Boston, homosexuality was removed completely from DSM.

Socarides never forgot my role in the APA decision. Some years ago I tried to join the National Association of Research and Therapy of Homosexuality (NARTH), an anti-homosexual “professional” organization of which he was president. In a letter from Joseph Nicolosi, its executive director, I was rejected for membership because, “We consider your professional views and objectives as too radically opposed to ours.”

One of the criticisms leveled against the APA for removing homosexuality as a disorder is that science does not advance by a vote of hands. These critics forget that any list is produced by a group of people who vote for or against it in the first place. Science, I learned from my reading of diagnostic systems, has little to do with it. Ronald Bayer, in 1981, superbly documented the scientific and political battles that were fought within the psychiatric community over the nomenclature change. It’s a fascinating story to read. If Spitzer hadn’t been in the Hilton Hotel audience that day in 1973, the nomenclature change might not have occurred for years.

For the best account of the politics that led to the nomenclature change, see:

Bayer, R. (1981). Homosexuality and American Psychiatry: The Politics of Diagnosis. New York, Basic Books.

For a copy of the presentation before the Nomenclature Committee see:

Silverstein, C. (1976-77). Even psychiatry can profit from its past mistakes. Journal of Homosexuality, 2(2), 153-158.

For more information about the ad hoc committee see:

Silverstein, C. (2009). The implications of removing homosexuality from the DSM as a mental disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 161-163.

Silverstein, C. (2011). The Initial Psychological Interview: A Gay Man Seeks Treatment. Elsevier Insight Press.