All hail January. The first was not just New Year's Day, but the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation. A couple weeks later, Barack Obama, our first black president, had his second inauguration ceremony on Martin Luther King Day.

I remember a lot of (white) people were pissed off when a reluctant Ronald Reagan signed MLK Day into law in 1983. Accusations of pandering were made. It was done just to keep black people happy. What had the guy really done after all?

To be honest, I didn't know. It took me years to understand the deliberate holes in my country's history. Partly because in high school, we never did get past World War II. The teacher was a football coach, and easily distracted. I should be generous and assume that people who resist queer history and queer lives are ignorant, but educable, like me.

The confluence of events — ending slavery, MLK Day — helped set the stage for Obama's inaugural speech that called on Americans to look backwards as well as forward, understand ourselves in the light of history. For once, Obama didn't mince words. Framed by the struggle to end slavery and racism, he attacked inequality from the first.

“… what binds this nation together is not the colors of our skin or the tenets of our faith or the origins of our names. What makes us exceptional — what makes us American — is our allegiance to an idea… that all men are created equal…”

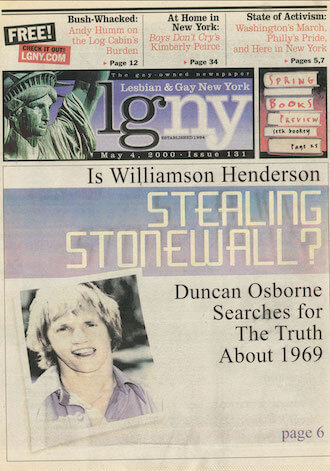

Of course, believing in equality doesn't make us exceptional at all. France, for example, has that whole liberty, equality, fraternity universalist presumption. But establishing the idea of equality as the tie that binds us was still a huge move on Obama's part. It resonated through the speech, especially when he linked Seneca Falls, Selma, and Stonewall in one breath, pulling us all into America's fold.

That was the first time gay people had been mentioned in an inaugural speech. The first time Obama linked our fights unequivocally. Women, people of color, queers. It's a no-brainer if you believe equality is something a democracy should strive for. If you believe it's important to emphasize the “human” part of human rights.

As Americans, though, I'm not sure how deeply that idea binds us. We usually want equality for ourselves, not everybody else. In New York, we stare across the subway at each other like we're not just of different races and genders but of different species altogether, even if we all began life with the same essential equipment — a heart, brain, lungs, a skeleton, skin of some color over it.

I'm not sure what does hold us together. Habit? “American Idol”? Politicians often refer to America as “this great land of ours” as if other continents found unity inevitable, and what bind us are mostly geology and the shared flag that waves over it. Ideas have nothing to do with it. In fact, we tend to mistrust them.

Americans are a practical people. We perfected mass production of cars and iPhones and apps. Unions don't demonstrate for unity, but for something concrete like salaries and working conditions — weevils in the bread, insufficient circuses. You can't build movements around abstractions. That's why we ended up with identity politics and single-issue activism. Which drives everybody crazy with its contradictions.

Ideally, activists keep their vision expansive and narrow at the same time, breaking down huge problems like homophobia or racism into smaller parts, like same-sex marriage or the overwhelming incarceration of young black men, at the same time trying to keep in mind how it all fits in.

The other conundrum is that while we have to get people to see and respect differences, we also have to make them difference-blind. Particularly when it comes to shaping culture and enforcing the law. We demand, “See me as the same and equal to any other human, but see me. Me.”

We often end up focusing on the particularities, and convincing ourselves our specific fight is special. We establish hierarchies, pit oppressions against each other. Class against gender. Race against sexual identity. We forget that we are part of the larger struggle for equality and freedom that extends well beyond this country and pretty much defines the human condition.

Maybe only visionaries like King can pull it off. He had a talent for walking that line. Weaving it all together until a fight for a black student to sit at the lunch counter next to some white guy became a symbol of the fight for human dignity, the American Dream. Maybe we should repeat this like a mantra: Seneca Falls, Selma, Stonewall. Three fights. Same DNA.