Renato Seabra, who was convicted of second-degree murder on November 30.

After deliberating for roughly a day, a Manhattan jury convicted Renato Seabra of second-degree murder in the 2011 killing of Carlos Castro, a 65-year-old Portuguese TV personality.

“This was a brutal and sadistic crime, where Renato Seabra bludgeoned, choked, and mutilated his victim before murdering him,” District Attorney Cyrus R. Vance, Jr., said in a November 30 statement. “But the jury’s verdict now, finally, holds Seabra accountable. It is particularly tragic that Carlos Castro was not only betrayed by his spurned lover, but met a very painful and violent end far from his home.”

Jurors were charged by Daniel P. FitzGerald, the judge in the case, on November 29, and they deliberated for roughly 90 minutes that day. They returned a verdict by roughly 3:45 pm the next day.

The speed with which they reached a decision suggests they never seriously considered the defense claim that Seabra, 23, was insane at the time of the murder and therefore not legally responsible. Jurors weighed if Seabra was guilty of murder two, not guilty –– a verdict they were never going to return since both sides agreed he killed Castro in their Midtown hotel room early last year –– or not responsible.

David Touger, who defended Seabra with Rubin M. Sinins, declined to comment.

A 2011 study by Russell D. Covey, a law professor at Georgia State University, on insanity defenses, published in the Boston University Law Review, cited a 1997 study that concluded an insanity defense is used in 0.1 to 0.5 percent of US criminal cases and is only successful one out of four times. Jurors perceive the defense as a get-out-of-jail-free card.

In his opening statement, Sinins told jurors that defendants who are found not responsible undergo another legal proceeding in which a court decides if they are still dangerous and must be institutionalized. Touger repeated that in his closing remarks. One defense expert, Dr. Roger Harris, a psychiatrist, told the jury that some defendants who are found not responsible are held for life.

But in her closing argument, Maxine Rosenthal, who prosecuted the case with Jun Park, told jurors that Touger could not “guarantee” what the outcome of the subsequent legal proceeding would be should they decide Seabra was not legally responsible for Castro’s killing.

The defense used Harris and Dr. Jeffrey Singer, a psychologist, to argue that the symptoms observed by doctors and staff at St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital, where Seabra was first treated just a few hours after the January 7 murder, Bellevue Hospital, where he was held until his transfer to Rikers Island three months later, and the city’s Department of Correction showed he was suffering from a serious mental illness. The defense wanted jurors to infer that Seabra was insane at the time of the killing.

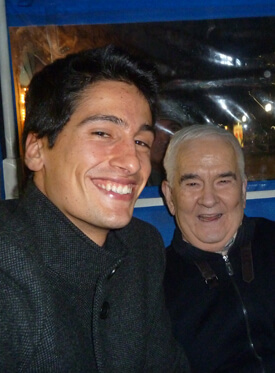

Renato Seabra and his victim, Carlos Castro, the week of the gruesome murder. | MANHATTAN DISTRICT ATTORNEY

The defense also cited the gruesome nature of the crime. Seabra strangled, beat, and castrated the victim. He told the two defense experts he believed he was acting on orders from God to eradicate homosexuality from the world. In varying accounts, Seabra said that after making superficial cuts to his own wrists, he either placed Castro’s testicles on his wrists or wiped the blood from Castro’s testicles on his wrists.

The prosecution’s expert, Dr. William Barr, the director of a neuropsychology unit at the NYU Langone Medical Center, told jurors that Seabra's symptoms were likely the result of the killing, and he raised the possibility that Seabra was faking his illness though he never said that definitively.

The prosecution argued Seabra was using Castro for money and to advance his modeling career. When Castro told the younger man they would be returning early to Portugal from their New York City vacation and that their relationship was over, Seabra flew into a rage and killed Castro.

Rosenthal delivered a highly effective closing statement.

The case took on a very personal tone as the skilled lawyers on both sides fought, frequently angrily, over the law and testimony. FitzGerald appeared exhausted by the acrimony at times.

During Touger’s closing statement, Gay City News observed that three jurors appeared to have fallen asleep at moments, so when Touger was heard discussing a fourth juror who was snoring, the newspaper asked him about that juror just before court proceedings were due to resume.

Touger objected to Gay City News mentioning the sleeping jurors in an article and asked if the newspaper had seen other jurors nodding their heads vigorously in agreement during his closing. When this reporter said he had not seen that, Rosenthal, who never talks to the press, said she did not see that either. When Touger asked if this reporter had seen a juror quietly saying, “Absolutely,” during his closing, this reporter said he missed that and Rosenthal chimed in that she missed that, too.