No one could have predicted how much the COVID lockdown would get American audiences off new Hollywood releases’ consumerist treadmill. Drive-ins have experienced a surprise revival, with new indie horror films like “Relic” and “The Rental” currently playing there alongside revivals of the likes of “Jurassic Park.” Given that there’s little else to see, as far as new releases, they’re likely finding a bigger audience than they would have under normal circumstances.

Another effect has been that theaters like Film at Lincoln Center have been presenting revivals of films largely unknown in the US. They did it earlier in August with two films made in the ‘60s by Portuguese director Paulo Rocha and are now showing Robert Kramer’s 1989 hybrid docufiction “Route One/ USA.” In early September, they will be streaming the first American release of Daniele Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub’s excellent “Sicilia!”

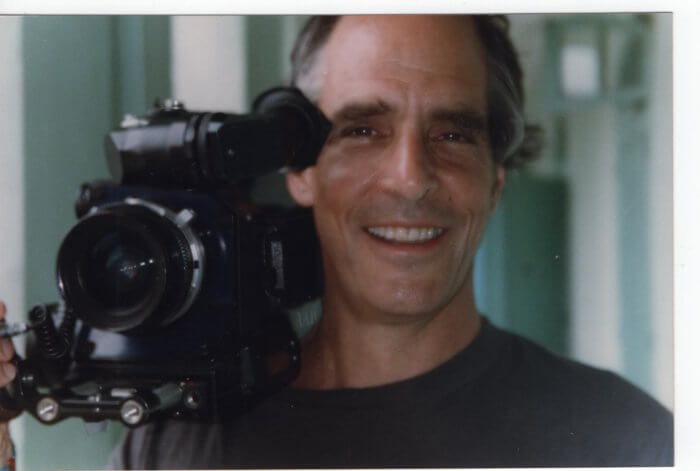

Ex-pat filmmaker Robert Kramer returned to America in ‘89 for one long last look

Kramer’s work is inseparable from New Left politics. He was one of the founders of the radical documentary group Newsreel. His best-known film “Ice,” made in 1970, depicts a group of leftist revolutionaries fighting a near-future fascist America. But five years later, his three-hour “Milestones” tried to take the pulse of the counterculture in an environment growing colder to such endeavors. It was well received in France but ignored or rejected by American audiences. This response convinced Kramer to move to Europe. From that point on, most of his work was made in Portugal and France.

In the summer issue of Cinema Scope magazine, Jerry White wrote, “About six months ago, France was having a real Robert Kramer moment,” referring to last November’s Cinémathèque Française retrospective as well as the first video release of his 1980 film “Guns,” by Re:Voir.

Kramer, however, returned to the US to make “Route One/ USA.” The film does something unusual, having real people interact with the fictional character Doc (Paul McIsaac.) Doc makes his third appearance in a Kramer film, following “Ice” and “Doc’s Kingdom,” where he had increasingly come to be a stand-in for the director’s own experiences. As “Route One/ USA” begins, he rides on a ferry approaching Manhattan, with the Statue of Liberty and World Trade Center coming into view. But as the film’s title suggests, it follows Doc down the title highway, from Maine to Florida.

“Route One/ USA” starts off looking like a political documentary and spirals out, becoming more mysterious in its second half. Kramer obviously shot far more material than he could use. As a result, we get brief glimpses of Doc’s travels, often with no explanation of exactly where he is. The character drops in and out of the film in its last hour. Kramer’s presence as director, cameraman, and occasional offscreen voice is always felt.

The film both feels part of a tradition of road movies and breaks with it. For one thing, Doc walks down Route One instead of riding in a car. Kramer seems enamored of trains and their tracks. Its images sometimes lean toward avant-garde abstraction, as much as “Route One/ USA” is fascinated by people. Its relationship to character is sketched in lightly rather than spelled out fully. As Doc watches a bingo game, he reminisces about his mother; traveling to an army base brings out memories of his own military experience. But McIsaac and Kramer had little conviction in making him a “believable” character. (While he was based on Kramer’s own life, the original idea for Doc came from a documentary by art theorist John Berger.) “Route One/USA” doesn’t lose much when Doc vanishes from it.

The tentative hope of “Ice” is gone from “Route One/ USA.” Filmed during the presidential campaigns of 1988, the film catches a glimpse of both Pat Robertson and Jesse Jackson running for that office. But the army recruiter who complains about the permissiveness of the ‘70s and praises the conservatism of ‘80s men might be seeing things as they are — at least about the latter. Right-wing Christianity dominates the country Doc returns to, and racism has grown ever more entrenched.

Kramer had a genuine curiosity about American life in 1989. The film’s editing choices make his opinions clear. He cuts between a Latinx teenager talking about facing jail time for riding with friends in a car he didn’t realize was stolen and a middle-aged white man discussing how he’s been rewarded by life in a comfortable suburb for prosecuting juvenile offenders. But “Route One/ USA” isn’t interested in judging individuals. It also uses cross-cutting throughout in more allusive, less political ways, as when Kramer edits between a man talking about his experience returning from the army and a brick wall being built.

“Route One/ USA” plays like an eccentric synthesis of Wim Wenders and Frederick Wiseman. It has the latter’s monumentalism but none of his interest in spending hours investigating institutions. In fact, Kramer’s film has trouble sticking to the same subject for more than a few minutes. Its structure gets looser and looser as the end of Route One approaches. While Doc decides to settle down in the US, Kramer saw what he wanted from the country, went back to France, and continued working until his death in 1999. Although “Route One/ USA” expresses a clear, thoughtful political view, it is closer to a poem than a State of the Union Address or an issue documentary.

ROUTE ONE/ USA | Directed by Robert Kramer | Icarus Films | Starts streaming Aug. 21 at Film at Lincoln Center; filmlinc.com

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.