BY DAVID SHENGOLD | Visiting Colorado's two opera companies takes the breath away on a literal level; altitude aside, both mounted bracing June productions.

Central City began its festival season on June 6 with the local premiere of “The Rape of Lucretia,” in a strongly cast, assured production by Paul Curran. In his presentation of the Male and Female Chorus (Vale Rideout and Melina Pyron), Curran did not dispel the problematic nature of the libretto's anachronistic eruptions of a Christian gloss — the pair, in '40s black evening wear, holding books, knelt with held hands in prayer at such moments. In other respects, they were plainly working through their own relationship in recounting the ancient Roman story; Rideout demonstrated how the Male Chorus' relationship to Tarquinius' deed simultaneously was one of enabling attraction and of revulsion, and Pyron's character echoed, slapped, or comforted him as the ancient drama mirrored their own unspoken story.

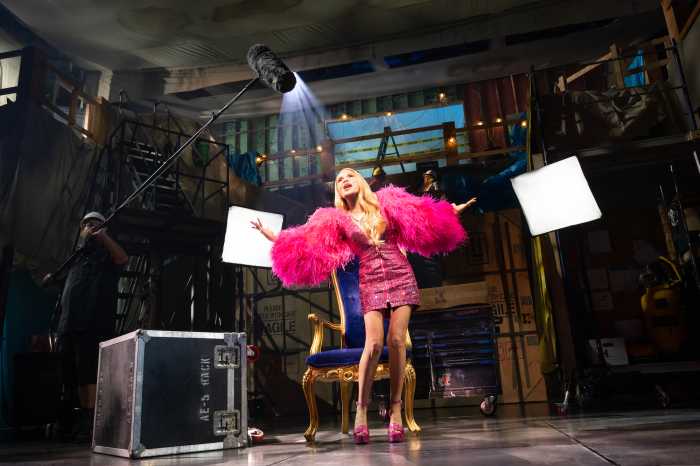

Denver's Adams, Central City's Britten score.

Kevin Knight's set, a stark wooden cabin ostensibly more suited to “Paul Bunyan” on a platform, with some stairs and a small fountain downstage center, banished any thought of togas and sandals. In a program interview Curran plausibly cited “Britten's abhorrence of war and violence, and of over-the-top machismo masculinity” as justification for the postwar setting.

But the image of Tarquinius (the excellent Brian Mulligan) as an American soldier, complete with recreational baseball glove, and Collatinus and Junius (Arthur Woodley and Joshua Hopkins) in British uniforms would seem to position violent, macho America as Etruria to Britain's worthy Rome — an analogy that breaks down historically no matter which way one pursues it, not least in the period of the opera's composition.

Where does such an analogy leave Junius, who instigates and profits from the rape to seize power – and how does that relate to the current catastrophic adventurism in Iraq? Tony Blair?

The purely psychological aspects of the characters' relationships were, however, tellingly evoked by Curran and his cast. That superb artist Phyllis Pancella grounded the evening as a compelling, multifaceted Lucretia — not neglecting, as some do, her inherent sensuality. She looked well, crafting a portrayal rich in detail of movement, glance, and utterance. In the intimate acoustic, her richly colored mezzo's lower register could be appreciated.Mulligan fielded an extraordinary baritone, clear and ringing, with spot-on diction. Unlike today's usual “barihunk” Tarquinius, he is not pantherine in form or movement and did not prowl or pose. The staging deflected what one might call its “obligatory Nathan Gunn moment” onto the more gym-toned Hopkins, whose Junius took an unmotivated sponge bath in his T-shirt. During the First Chorus' galloping “Ride Narration” Tarquinius unhurriedly shaved and got dressed. Mulligan instead resembled an overgrown spoiled child — think Kevin James in “The King of Queens” — not to be denied his whim; his physical and vocal size leant a sense of menace.

Rideout, a fine musician, was admirably accurate and ductile but lacked timbral fluidity; at first projecting cleanly rather than inhabiting his (admittedly sometimes awkward) words, he warmed to his task. Pyron emerged less even — sometimes the tough ascending intervals written for Joan Cross found her sharp — but her refulgent soprano, etched phrasing, and highly charged emotional investment made for an arresting performance.

The handmaidens, Maria Zifchak (Bianca) and Sarah Jane McMahon (Lucia) were vocally splendid and finely contrasted dramatically. Zifchak's emotional honesty matched Pancella's. Woodley proved dignified and vocally mellow; Hopkins' dark baritone showed excellent promise, but he has yet to master the art of varying inflection on repeated textual phrases.

Damian Iorio made a highly creditable US debut, keeping fine ensemble with the singers if somewhat less consistent control of the pit — probably a case of a few first night kinks. His presence was not so transfiguring as to dispel fears that Curran, in his post as “British talent scout” for the company, won't automatically advocate British conductors where Britten and Handel are concerned — common practice with British administrators in North American houses and no more apt than would be British theaters insisting on Americans leading Bernstein or the Broadway works of Weill.

Central City continues through August 10, with Emily Pulley and Grant Youngblood in “Susannah” and McMahon headlining Ken Cazan's staging of “West Side Story.”

The following night Opera Colorado opened John Adams and Alice Goodman's “Nixon in China” at the spectacularly refurbished Ellie Caukins Opera House. Seen widely since its 2004 Opera Theatre of St. Louis origins, James Robinson's entrancing multimedia production merits continued exposure; a pity Gerard Mortier has inked the veteran Peter Sellars production instead for City Opera. Company debutant Marin Alsop had led the work back at OTSL; her driving, dynamic leadership proved central to the musical success of the evening.

Many of the leads had danced and toasted through this pleasing – and maybe just a bit too anxious to please -but vocally demanding opera before. Robert Orth captured Nixon's clenched-shouldered stance and unnatural smiles with almost unsettling precision. Any young Anglophone singer could profitably attend to Orth's sovereign wedding of text to fine-drawn musical lines – every word and note carried with impact and intention.

Maria Kanyova sang with her accustomed clean line and lustrous top; one cannot fault the soprano for being too slim and beautiful for Pat Nixon! She moved and acted expertly, proving touching; what was not conveyed — the maladroit pathos of this eternal Washington outsider — may not be in Adams and Goodman's conception.

Tracy Dahl, her coloratura and tone undiminished since her youthful Oscar and Olympia days, gave phenomenal voicing and energy both to Madame Mao's theatrical outbursts and her high, nostalgic lines in Act Three. Kanyova and Dahl made their highest-set lines intelligible.

Chen-Ye Yuan (Chou En-lai) showed a chamber-format baritone that vanished in ensembles, but Alsop was very considerate with his eloquently voiced solo contributions. Tenor Marc Heller, fearless in the upper register and a deft contemporary stylist, made a convincing Mao both visually and emotionally.

If rough of timbre, Thomas Hammons, the original Kissinger — so to speak — remains an excellent comic sight gag; not much more is required here. (One doubts Chilean or Cambodian audiences would be amused.)

What cultural historians ultimately make of this opera's personalizing take on Nixon remains to be seen. Denver took the fine performance to heart; a visitor who spent his early boyhood shouting partisan abuse at the 37th president's televised image found himself unexpectedly moved at the evocation of an American commander-in-chief both publicly admitting having been wrong and staking his reputation on the desperate necessity for multilateralism in foreign affairs.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.