In May of 1925, Ossian Sweet, an African-American doctor, and his wife, Gladys, purchased a home in a predominantly white neighborhood in Detroit. They moved in three months later and began receiving threats. One evening, the home was besieged by an angry white mob.

Between the time the Sweets purchased their home and hostile neighbors gathered outside it, Alexander Turner, also an African-American doctor, and his wife had been driven from their home in a Detroit white neighborhood. Described as a “professional acquaintance” of Alexander’s in “At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America,” a 2003 book by Philip Dray, Sweet was apparently aware of Turner’s experience and had stockpiled weapons and ammunition. Sweet’s brother, Henry, shot and killed one member of the racist mob massed outside the house. Police arrested the Sweet family for murder.

The noted attorney Clarence Darrow represented the Sweets. Their first trial ended in a hung jury. Henry was tried alone at the second trial and acquitted. The charges against the rest of the family were then dropped.

For one white religious leader in Detroit, the solution to this conflict was simple — segregation.

“Some desirable section of the city should be set aside for the colored population,” the Reverend Frank D. Adams, pastor of the Universalist Church, said in a 1925 issue of the New York Amsterdam News. “See to it that the schools, the sanitary conditions, and the like are equal to those enjoyed in any section of the city by the average white wage earner. Make it possible for the Negro to secure homes here at a reasonable price and terms and keep whites out of the district.”

Adams, who was elected to the presidency of his denomination in 1927, was not the first pastor to endorse a racist policy. The Southern Baptist Convention was founded in 1845 due to a schism among the American Baptists over the morality of slavery. The Southern Baptists, who in 1995 apologized for supporting slavery and segregation, were not alone in supporting these immoral institutions.

Dray quoted Walter White, a senior officer in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), who in 1929 said, “It is exceedingly doubtful if lynching could exist under any other religion than Christianity… No person who is familiar with the Bible-beating, acrobatic, fanatical preachers of Hell-fire in the South, and who has seen the orgies of emotion created by them, can doubt for a moment that dangerous passions are released which contribute to emotional instability and play a part in lynching.”

But there came a time when no denomination would defend slavery, and later none would defend segregation. In 1954, the US Supreme Court struck down segregation in schools, and the Southern Baptists told their members to obey the law. It was white politicians and the white grassroots that most visibly opposed desegregation.

In contrast, much of the infrastructure that was used by secular institutions to attack the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community has been dismantled over the past five decades.

Starting in 1962, sodomy laws were slowly overturned, then banned altogether by the US Supreme Court in 2003. In 1973, homosexuality was taken off of the American Psychiatric Association’s list of disorders. In 2011, the military ended its ban on open service by gay men and lesbians. The public and private entities that used these laws and that diagnosis now back the community.

“These are no longer leading the charge against, in fact, they’re on our side,” said Evan Wolfson, president of Freedom to Marry, a pro-gay marriage group. “The leading force does its work in the name of religion.”

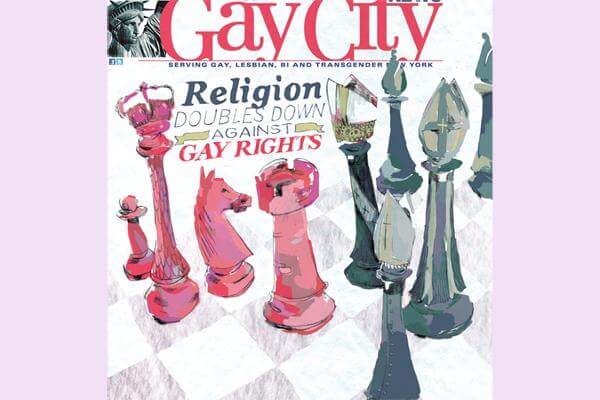

Religious conservatives have doubled down in their opposition to all things queer. Today, the community’s most visible and most vocal opponents are the leaders of the nation’s major religions.

The successful 2009 ballot fight to overturn Maine’s gay marriage law was led by the Roman Catholic Church, though the church is less involved in this year’s ballot vote to enact marriage for same-sex couples there. Mormons supplied 40 percent of the cash, by one estimate, and tens of thousands of volunteers in the effort to pass California’s 2008 gay marriage ban. Roman Catholic bishops are actively supporting gay marriage bans in four of the five states that will vote on marriage this year.

Religion is clearly an influence in the ballot initiative votes. A 2006 study by Ken Sherrill, a professor at Hunter College, and Patrick Egan, a professor at New York University, concluded that being a Republican or conservative, older, less educated, and religious, specifically a born-again Christian, were associated with support for marriage bans.

“Religiosity rivals the power of political beliefs in explaining the vote on the marriage amendments,” the authors wrote. That study mostly analyzed votes in the South. Religion becomes less important, though still influential, outside of that region.

A 2008 exit poll on the Proposition 8 vote showed that Catholics approved it 64 percent to 36 percent. Sixty-five percent of white Protestants backed it as did 81 percent of white evangelicals and 84 percent of people who attend church weekly.

That most US denominations will not marry gay and lesbian couples suggest that this opposition is common. At least seven denominations do marry same sex couples, and some of those have been doing so for decades. But those religious voices are rarely heard from in the mainstream debate.

“There’s a frame out there that religion is antagonistic to LGBT people,” said Sharon Groves, director of the Religion and Faith Program at the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), the nation’s largest gay lobby. “We haven’t been able to put forward a convincing alternative frame… That needs to get out there and register with people that religion is not a monolith.”

HRC, the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, and the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) all have programs that organize among religions, but that progress has been slow. HRC’s view is that the results of that work will be seen in the votes this year.

“I think that you’re going to see what the polling has shown, that people of faith are diverse and that there are many who are supportive,” Groves said.

Gay groups cite opinion polls that show increasing support for same-sex marriage, including among Catholics and white mainline Protestants. Polls, however, can be illusory while votes leave no doubt. Going into the Prop 8 vote, one poll showed Catholics narrowly opposing the ban. The shift from opposition to support among Catholics alone accounts for the amendment’s winning margin.

This also shows a natural advantage that religious leaders enjoy. They speak to their followers regularly in temples, churches, and mosques. Gay groups do not have that access. In a 2008 story in the San Francisco Chronicle, Mark DiCamillo, director of the Field Poll, said “The Sunday before the election is just a very influential time for churchgoers… [T]here was a lot of interest and attention and concern on this whole issue, but they brought it to a big conclusion on the final weekend.”

Wolfson said the community has to push supportive religious leaders forward.

“There needs to be much more investment into elevating those voices,” he said. “I think that the clergy and people of faith who have opened their hearts and minds and moved past the stereotypes and prejudices of the past have to take on the responsibility for speaking out.”