Superstar singers deliver the goods (for a change)

The city recently witnessed three concerts involving some of the very few classical vocalists still headlining recording projects. That all three events proved highly worthwhile flew in the face of much critical and fan-based grumbling about dwindling standards. One does regret, in this regard, that the Newspaper of Record chooses to devote so much of its shrinking vocal music coverage to touting crossover frauds like Josh Groban and Britain’s Russell Watson and Amici Forever; British audiences apparently have an undiminishable thirst for this watered-down, airbrushed junk.

On January 20, the Prague-born Magdalena Kozená, who made an enchanting Met debut in November as a sexy, silken-voiced Cherubino, returned to make an impressive recital debut in the depths of Zankel Hall. This was my first visit to the beautiful newly refurbished Carnegie stage, on a site where I soaked up many Renoir and Fellini movies as a teenager. With music on this quiet scale––a big jazz or world music ensemble should do fine––it is too bad about the recurrent subway noises, which put me in mind of the eerie offstage rumbles Verdi contrives for Radamès’ offstage trial in “Aida.”

Kozená is a gorgeous, elfin blonde (well… blonded) young woman who carries herslf with grace and piquant charm reminsicent (as is her soft-grained tone and vocal production) of the late, much-lamented Lucia Popp. Popp’s voice was of course more highly placed when she was Kozená’s age––Popp began her career as a Queen of the Night and ended it as an Arabella and Marschallin. Kozená, like Bartoli and Kirchschlager and Ann Murray before them, bills herself as a mezzo, but despite haviing nice plush colors to offer in the middle and a solid bottom register, she sounds like a soprano to me. Why argue? She’s still developing both vocallly and in artistry, but what ‘s there already is choice.

She didn’t command the tonal reserves to do justice to three Mahler songs, but was quite ravishing in groups by Martinu, Dvorák, and Beethoven’s contemporary Jan Josef Rosler, who wrote songs in German. She also offered a light touch and good French in Ravel’s (to my taste) overarch “Histoires naturelles,” with their verbose animalian and avian evocations.

It was good to hear an attractive young voice in Shostakovich’s trenchant 1960 “Satires;” it’s too bad Carnegie didn’t obtain more accurate and pointed translations for Sasha Cherny’s poems. Kozená was in full command of the words’ meaning and flow, lacking only proper reduction of Russian vowels ( so we heard for example “poh-ET”, pronounced as if in French, instead of “pah-EYT”). It would be nice to hear her in many of Tchaikovsky’s songs. The first encore, Dvorák’s heartstring-tugging “Songs my mother taught me,” was irrestistably magical.

The presence of Malcolm Martineau at the piano guarantees an ultrasmoooth, well-articulated accompaniment and he provided considerable pleasure; maybe his tone was a little oversuave for the acidic Shostakovich cycle.

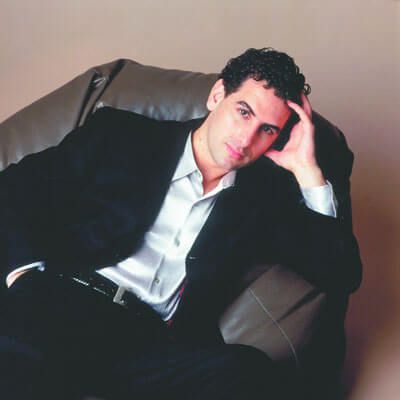

Juan Diego Flórez made his own quite triumphant local recital debut in a sold-out Alice Tully Hall on January 25. Virtually everything you have read about this Peruvian lyric tenor, opera’s current “It Boy,” is true. The voice is pretty (if rather narrow of tonal compass), the agility extraordinary and the stylistic distinction in Rossini’s and Donizetti’s music admirable, especially in one barely past 30. (And, unlike some “CD cover babes” of both sexes, he looks just as scrumptious live as in publicity photos.) His French in the Gluck selections and his “party piece,” the nine high C “Fille du Régiment” aria “Pour mon âme” was as fine as his Italian and (of course) native Spanish elsewhere. My only quibbles would be that he doesn’t always sustain a very long breath line, thus tending to fade out at the ends of phrases, and that he doesn’t seem to be able to trill—a fault common to many of today’s greatest singers.

Flórez seems very wise about what roles he’s going to take on, and one longs to hear him in all of them. Meanwhile, the Met offers his sterling Lindoro in Rossini’s “Italiana in Algeri” through March 17. If you’ve ever been wary of opera, this is a fun show that anybody would enjoy, and with Olga Borodina, Lyubov Petrova, and Marius Kwiecien also involved, there will be much to see and hear. Vincenzo Scalera––whom one is used to seeing with veterans like Carlo Bergonzi––accompanied Flórez’ recital bow before le tout New York discreetly and aptly.

The New York Philharmonic presented an exceptional treat on January 29, a program with Riccardo Muti and Thomas Quasthoff that had been televised the night before. (Yes, a classical concert that did not involve Renée Fleming actually made it onto public television!) Maestro Muti, still wondrously black (or blackened) of mane but now sporting those pink-tinged indoor sunglasses beloved of Italian Cinecittá stars past 30, should be invited back often for the elegance, unforced flow, and utter lack of interest in tonal glitz (a besetting sin of the Philharmonic’s current music director, though one welcome when called for).

The orchestral playing was quite lovely in Schubert’s ethereal “Zauberharfe” overture, a fine program opener, and continued its delicacy for the four Mozart concert arias illumined by Quasthoff’s profound but comfortably-worn artistry. Unlike Thomas Hampson, who has also sung some of these pieces exceedingly well in this same hall, Quasthoff never adopts a manner suggesting High Aesthetic Improvement bestowed on his audience. The helpful program notes by James Keller made the point that these are not static or secondary pieces in Mozart’s oeuvre but served a variety of functions, including as subsitute arias in operas by other composers: the delightful “Rivolgete a lui lo sguardo” actuallly was replaced in “Così fan tutte” before it opened with the simpler “Non siate ritrosi.” (That doesn’t just happpen on pre-Broadway tryouts!) Quasthoff’s wit scored big here, but he also brought moving feeling to the legato sections of “Per questa bella mano” and “Non sò d’onde viene”.

His well-projected, wide-ranging voice, boasting high note “ping” and ravishing sheen on the baritone end proves a little more compact and pale in the lowest bass reaches. But the artistry, musical aplomb, and commitment to text are exceptional throughout. The one fault was (here again) an inability to supply the trills both the second and fourth arias demanded. But these were terrific performances. One hopes New York soon hears Quasthoff in a suitable operatic role: perhaps Mozart’s Sprecher or Wagner’s Amfortas or Kothner?

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes for Playbill, Time Out New York, and Opera News, among other venues.