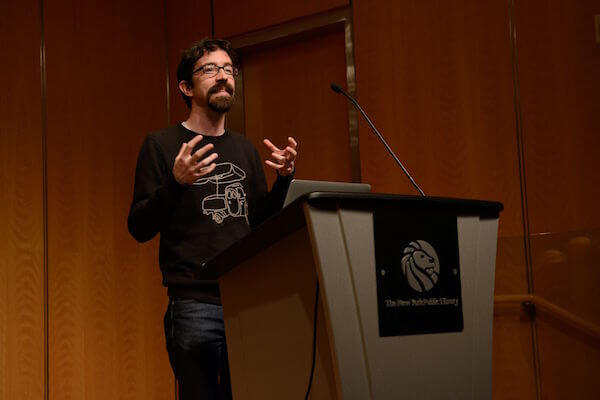

Speaker Meredith Talusan, a transgender author and activist, at one point tweeted in wonderment at all the firepower raining down on the Human Rights Campaign at the conference. | ALICE PROUJANSKY

Roughly two hours into a conference titled “Beyond Marriage, Beyond Equality,” Meredith Talusan, a transgender author and activist and a conference speaker, tweeted “Wow so much @HRC-bashing among queer academics has me thinking, ‘But they’re trying.’ Who have I become???”

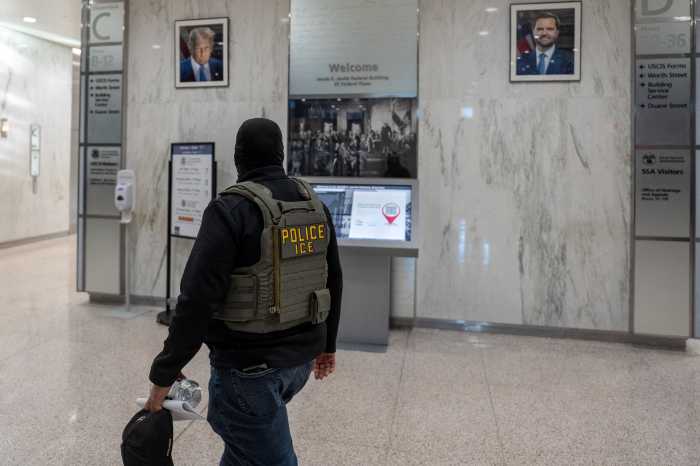

The conference, which was organized by historian Martin Duberman and held at the main branch of the New York Public Library, featured Duberman and six queer left academics on two panels. Much of the discussion at the conference was concerned with what the panelists oppose and what they enjoy criticizing –– the drive for equality under the law by mainstream LGBTQ groups and same-sex marriage.

Duberman opened the conference by noting that movements that have radical left roots often see the founders “pushed off stage” and replaced by others with a narrower vision or more limited goals.

“I think we’ve seen something like that pattern in the movement for gay liberation,” he said at the April 22 event.

Five hours of critique that even one critic could not bear

During the discussion, the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), an early and short-lived far left group that emerged following the 1969 Stonewall riots, was held up as an example of the movement’s radical roots and the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), the nation’s largest LGBTQ lobbying group, was held up as the embodiment of the moderate –– some of the panelists would say conservative –– impulse that supplanted the movement’s radical politics.

Columbia Law School Professor Katherine Franke said, “Only one thing has changed from 1971, gay and lesbian couples are marrying.” | ALICE PROUJANSKY

Katherine Franke, a professor at Columbia Law School, began her comments with a rhetorical tactic that is commonly used by both the far left and the far right –– asserting that the state of society is terrible and so radical politics are called for. She compared 2017 to the early ‘70s when sodomy laws were enforced in nearly every state and no jurisdiction barred discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity.

“If we fast forward 50 years to today, we are by and large fighting the same fights,” Franke said. “Only one thing has changed from 1971, gay and lesbian couples are marrying.”

Some of the panelists were concerned with the movement abandoning the critique of capitalism made by a few groups from that time. Some early gay rights groups, such as GLF, shared the goals and ideology of anti-racism, anti-poverty, and socialist organizations, though they did not necessarily establish links to those groups.

“We’ve gone from trying to dismantle a system to trying to get inside it,” said Hugh Ryan, a writer and recipient of a Martin Duberman Fellowship as visiting scholar at the Public Library.

That abandonment aided the push for same-sex marriage, in Franke’s view, because lesbian and gay couples were compared favorably to the stereotype of the failed African-American family.

“In that sense, winning marriage benefited from a kind of racial endowment,” Franke said, after noting that she did not believe that marriage proponents were racist. “It was easier for us to say, ‘We’re like you, straight people.’”

The appeal to government and to the law that have been very much a part of the LGBTQ community winning recent gains was also criticized during the conference.

Michael Warner, a professor at Yale and author of “The Trouble With Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life,” said that during debates about the US Department of Homeland Security shuttering rentboy.com, a website that linked gay escorts and customers, he would inevitably find defenders of the criminal prosecution asserting that it was justified because prostitution is illegal.

“When did we start loving the law, and then I realized ‘Oh yeah, gay marriage,’” Warner said. “That love of the law has become far too pervasive.”

As is often the case at both extremes of the political spectrum, critiques are common and solutions are less common. That was certainly the case during the conference.

Joseph DeFilippis, a professor at Seattle University, discussed his study of eight small LGBTQ advocacy groups. | ALICE PROUJANSKY

Joseph DeFilippis, a professor at Seattle University, studied eight small organizations that he said showed an alternative way of organizing in the LGBTQ community and were addressing poverty and racism. Questioned by Duberman, DeFilippis said that not all of them are radical, the ones that are cannot be too radical, and all of them are constrained by their legal non-profit status.

“There’s only so much they can talk about without being written off,” DeFilippis said.

Lisa Duggan, a professor at NYU, touched on intersectionality during her talk, which is frequently used on the queer left when discussing organizing and setting goals. The term was first introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw, a professor at Columbia Law School, and she called it “an analytic sensibility, a way of thinking about identity and its relationship to power” in a 2015 editorial in the Washington Post. Intersectionality has no agreed-upon definition.

Hugh Ryan, a Martin Duberman Fellow at the New York Public Library. | ALICE PROUJANSKY

“It’s had a very strange career and many, many meanings,” Duggan said. “The term is all over social media.”

Talusan spoke last and nodded to the gloomy presentations that came before her.

“I’m not sure I’m going to be any less depressing, but at least I’ll be perky about it,” she said.