As mainstream American cinema has become utterly sexless under the new Hays Code of the PG-13 rating, visual representations of sex are all too often marginalized. Anthology Film Archives’ expansive series “Let’s Talk About Sex” brings together films on the subject from a particular angle. As the theater’s program notes state: “Ignoring the thousands upon thousands of movies in which sex is depicted (more or less explicitly) or visually suggested (more or less frankly), ‘Let’s Talk About Sex’ showcases those films in which sexual experience is conjured purely through the spoken word, by individuals verbally sharing their thoughts, feelings, and memories.”

One of the brightest points of the series is the way it brings together experimental shorts, documentaries and narrative features. (Steven Soderbergh’s “sex, lies and videotape” is the best known entry.) It shows how artificial these categories are. Similarly, its films share a wide range of perspectives emphasizing marginalized people’s sexual experiences.

French director Alice Diop’s “Towards Tenderness” is a documentary which massages its interviews with four men, one of them gay, towards a definite conclusion, if not a story. Diop spoke with Black Frenchmen about their experiences with love and sex. Until the final scene, no one is seen speaking on screen, and Diop hired actors to appear in scenes suggested by the voice-over, from a group of men eating at a Turkish restaurant to a trip to the red light district.

The first scene is not promising, as Diop talks to a guy who says he only sleeps with “bitches” and “hoes” while defending his choice of language by calling himself a “wanker.” But Diop’s interviews dig deeper, finding vulnerability in a hypermasculine culture. One man speaks about his attraction to a Muslim boy from Senegal, saying it went too far. The emotional desolation and absence of love described throughout the film goes further for him, as he describes a widespread attitude that being a top equals masculinity, even heterosexuality. While his words play on the soundtrack, Diop films a man wearing a backpack walking through urban streets. As its title suggests, the film does move towards an acceptance of emotional openness and away from the machismo of its early scenes. It’s nuanced and touching enough to look beyond the surface sexism and bluster of some of its subjects.

Cathy Cook’s 18-minute short “The Match That Started My Fire” looks back joyfully at girls discovering sexual pleasure for the first time. Based on the stories of 18 women, including the director herself, it lays their voiceover on top of a rapid-fire montage of scenes of undersea life, extreme close-ups of flowers and found footage of Americana. Its celebration of masturbation extends to the choice of images of women, which are erotically charged and hint at mild BDSM, and the rhythmic editing of the soundtrack. (Paul Dickinson composed an audio collage driven by drums, even incorporating a beeping phone as a musical element.) Cook looks at women with an appreciative erotic charge but refrains from framing that fragments or dominates the female body. “The Match That Started My Fire” is remarkably sex-positive; girls’ sexuality is frequently assumed to be defined by danger and trauma, but Cook leaves negative experiences off screen. Instead, she relates girls learning about their bodies’ capacities for pleasure by accident, climbing a rope, or resting against a washing machine. One woman describes having sex with another girl by grinding against her. The film’s library of images shows a sly wit, turning the sea into a physical space reflecting desire.

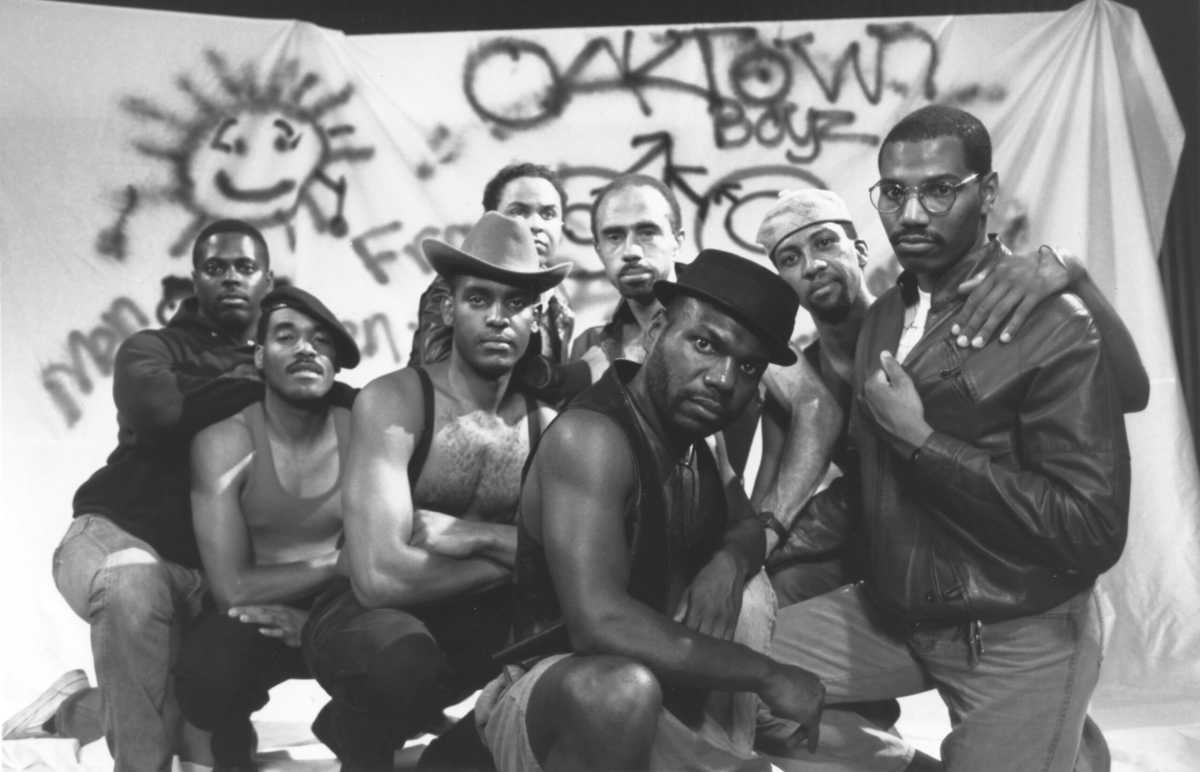

Marlon Riggs’ “Tongues Untied” hit with a ferocious impact upon its debut in 1989. Since Riggs received a $250,000 grant from the National Endowments of the Arts, the film became a political football. Its airing on PBS was attacked by far-right preacher Donald Wildmon and politician Pat Buchanan, who edited clips from the film into an ad claiming George W. Bush was financing pornography. It insists on the specificity of Black gay experience, with the opening chant “Brother to brother” and credo “Black men loving Black men is the revolutionary act.” Despite including interviews shot directly, its form draws from poetry and essays. Riggs collaborated with poet Essex Hemphill, who reads his work on screen. “Tongues Untied” attacks both homophobia in the Black community (with clips of Eddie Murphy at his peak of bigotry) and a gay scene defined by whiteness, showing the difficulty of living in these spaces.

Its editing makes many of its points. Although it wasn’t perceived as such at the time, “Tongues Untied” is a crucial part of New Queer Cinema and the rise of Black directors which took place in the ‘90s.

“Let’s Talk About Sex” | Anthology Film Archives | July 8th to 30th