“Minyan,” directed and co-written by out gay filmmaker Eric Steel (“The Bridge”), is an observant, melancholic, coming-of-age drama set in Brooklyn in the winters of 1986 and 1987.

The film, which is based on a short story by David Bezmozgis, has teenager David (Samuel H. Levine) grappling with being Jewish in the tight-knit Russian Jewish community of Brighton Beach and being gay in the era of AIDS. However, “Minyan,” is not a coming out story, but rather, it is an immersive drama that shows how David struggles to find a sense of self and belonging in both communities.

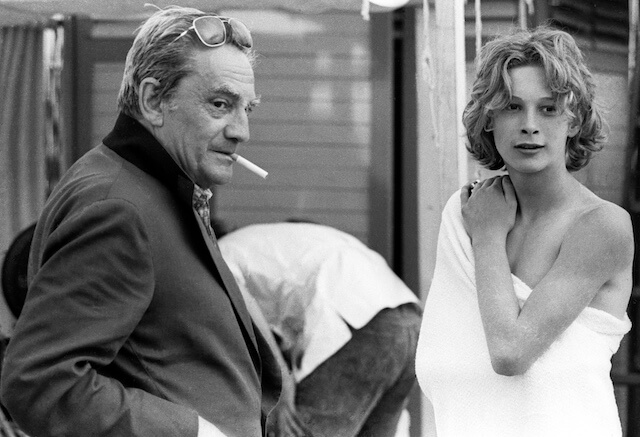

Despite friction with his parents, David is devoted to his grandfather, Josef (Ron Rifkin), who moves into subsidized housing. His neighbors are Itzik (Mark Margolis) and Herschel (Christopher McCann), two widowers who are now a discreet gay couple. David is also covertly exploring his own homosexuality, sneaking into a gay bar, and eventually becoming intimate with the sexy bartender, Bruno (Alex Hurt).

The film boasts an impressive, internal performance by Levine, and strong support from the entire ensemble cast. Steel chatted with Gay City News about his film.

KRAMER: “Minyan” uses James Baldwin’s writing, the song “Giant,” (with the lyric, “How can anyone know me/when I don’t even know myself?”), and other works to exploring identity. Can you discuss the film’s ideas of identity, religion, sexuality, and community?

STEEL: I read James Baldwin when I was in my early teens. When I went to boarding school, I discovered “Giovanni’s Room.” As soon as I saw this story in writing, I knew this life could exist somewhere. That push and pull between identity and being — who am I and where do I belong? — that was how I formulated things. I didn’t feel Jewish. I remember being one of the few Jewish kids in a WASPy grade school and the temptation to pretend I wasn’t Jewish — how strong that was. Those things work as pulls in my life, and I kept finding answers in books and poetry. When I found “Giovanni’s Room,” I didn’t want to give it back to the library. I wanted to keep the book. This was back in the day when you wrote your name in the book. Who else is reading this? Then I can find where I belong or who I belong with. Young people today take for granted that they will see representations of gay or queer people, and that is not the way the world was in 1980-1982. Gay bars didn’t have Rainbow Flags. You were knocking on a door and had no idea what was on the other side.

KRAMER: The film provides fragments of David’s life to piece together, which is a canny approach. What can you say about how you created the drama, which is more episodic?

STEEL: It is maybe my idea on how meaning, and the shape of one’s life, accrues as opposed to being patterned. I believe myself to be a queer storyteller. I think there is a queer way to tell a story. I saw how the story came together, where there were fragments that were happening in one part of David’s life that were informing something happening in another part of his life, like seeing [Itzik and Herschel’s] toothbrushes. That leapfrogging and stitch-work is how I tell stories naturally. The model for what a straight romance looks like on film doesn’t apply so easily in my experience, to gay life. Interruptions, omissions, and secrets are what you need, and learn to see. You learn them as a queer person but also as an immigrant — hide where you came from, hide your identity.

KRAMER: What observations do you have about the characters’ relationship with religion and its influence as a guiding force?

STEEL: I didn’t have a lot of Jewish education when I dived into this. One Rabbi told me, and he did not invent this interpretation — be kind to strangers because you were once a stranger in a strange land yourself. It is about these kindnesses, and things one person does to another person to help them move along on a journey. The idea of a minyan to me — I get it is the 10 men you pray with — but there is the gay family you build. There is also 10 men who come together around [David] and move him with prayer and want to help him move forward in this world. All of these people touch him in that way. Be kind to a stranger. Here is this young person who shows a genuine interest and wants to see and acquire knowledge and wants to learn so they move and guide him.

KRAMER: What can you say about the depiction of Itzik and Herschel? That relationship becomes quite important and more impactful to David than his other relationships.

STEEL: One thing that was important to me was this sense of transmission, what you are handing off. Joseph is imparting wisdom and experience he learned as a Jew. The same things are being transmitted by Herschel and Itzik, but you are seeing them in a slightly different phase. Later, the taxi driver is also imparting things to David. Even the bartender imparts wisdom to David.

KRAMER: Can we talk about David’s relationship with Bruno?

STEEL: To me, the 1980s was still a moment when there was a big question mark next to gay relationships. No one knows that Herschel and Itzik shared a bed. The person [Bruno] that David sees at the bar and is attracted to, brings him into his home and he is given access to another space. And I think Bruno is giving and not giving at the same time. There is a lot he is offering David — a sexual playbook, and a place to put his head. There is a connection. Whether it actually turns to romance or not, part of that is on Bruno. It’s not that Bruno is a heartbreaker; he knows what’s going on in the world. Bruno sees in this young man a version of himself.

MINYAN | Directed by Eric Steel | Opening Oct. 22 at the IFC Center | Distributed by Strand Releasing