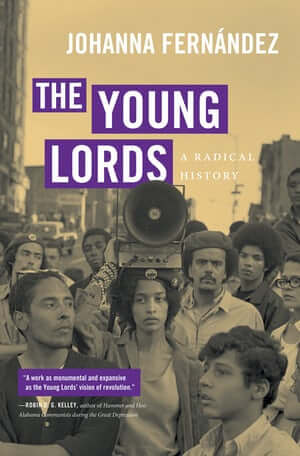

Johanna Fernández, child of immigrants from the Dominican Republic and a professor at New York’s Baruch College, has just published “The Young Lords: A Radical History,” a book about the 1960s Puerto Rican activist group. The Young Lords began as a Chicago street gang; then, inspired by the Black Panther Party, morphed into a militant rights organization that caught fire in New York City, where Jose Saldaña, child of Puerto Rican migrants to the city, was born.

Raised in impoverished East Harlem, Jose spent 38 years in New York prisons. On his release in 2018, he became the director of Release Aging People in Prison Campaign (RAPP) and a compelling critic of our criminal justice system. Johanna, for her part, has devoted years to the prison abolition movement, championing the release of imprisoned journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal.

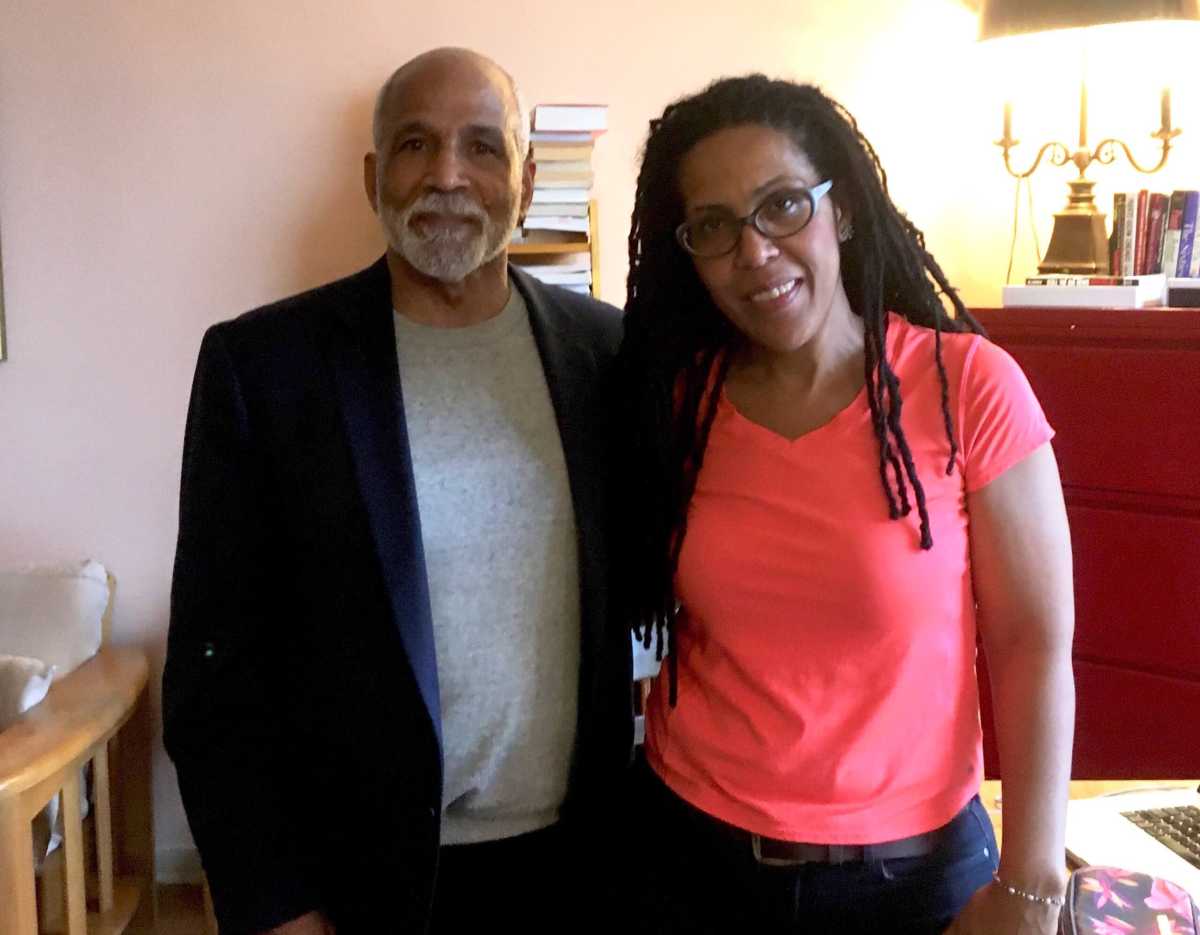

Johanna Fernández and Jose Saldaña talk about the Young Lords

In March, a few days before social distancing took hold, Jose and Johanna met with me in Johanna’s Washington Heights apartment to talk about the Young Lords: why Johanna wrote this book; how the Young Lords changed so many Latinx lives; and how the moral lifeline they gave Jose helped him survive decades in prison. Jose discovered the Young Lords when he was 18 years old.

JOSE SALDAÑA: I was a high school dropout, Spanish Harlem was my turf. And once my dream of becoming a baseball player faded, my next aspiration was to become a big-time drug dealer. One day, I was up on 111th Street and all these cops started showing up — they were everywhere. My sister comes running, she says, man, the cops are surrounding the church because the Young Lords are in there.

I hadn’t heard of the Young Lords, and I was pissed. They were bringing cops to the neighborhood, and cops stop business. See, I had no politics, no social consciousness, sometimes no moral consciousness.

JOHANNA FERNÁNDEZ: I write about that protest in my book. The Young Lords occupied the First Spanish United Methodist Church in December 1969 and again in October 1970. You’re referring to that first occupation.

SALDAÑA: Right. I went over to the church, and that was my introduction to the Young Lords.

FERNÁNDEZ: This was their signature protest. They occupied that church because, after a month of negotiations, they failed to convince the pastor to allow them to feed poor community children there. On December 7, 1969, the Young Lords make their request to the entire congregation. But, unbeknownst to them, the pastor had asked the cops in, undercover.

So Felipe Luciano, the Young Lords chairman, appeals to the congregation: “The church must address community needs. Here in this sea of poverty, with all your wealth, you turn the other way. If Jesus were alive today, he’d be a Young Lord…” Luciano got his arm fractured by the cops. Other Young Lords were beaten up, and some were arrested. That’s the backdrop to the occupation two weeks later.

Jose, how did you change your mind about the Young Lords?

SALDAÑA: Because I grew up in extreme poverty, killing rats in our apartment. The lead poisoning — I had to watch my baby brothers and sisters, because you know babies they pick up anything and put it in their mouth. We were aware of these health problems, but nobody gave a damn. With the Young Lords, for the first time, somebody started caring. People came and talked to us — a few women, especially.

We’re smalltime drug dealers — nobody there was big — and right there on 111th Street was a building where the prostitutes do their business, I was very close to some of them. The Young Lords was talking to them like they’re human beings. I’m saying, “Wow, nobody treats them like that.”

Growing up, everybody I knew was first-generation Puerto Rican, but it didn’t mean anything, except people didn’t like us. When the Black Panthers came out, they had an identity; we didn’t have that. The Young Lords gave me the identity I was missing and a social and political conscious. I started to connect things.

Like, when I was nine years old, I was befriended by a prostitute — very young, she might have been a 16, 17-year-old-girl. I used to run errands for her. She’d throw money out the window; I’d go get something for her; she’d try to give me a couple of dollars but I never wanted payment, because everybody hated them. My moms would always scream at me when she’d see me coming out of that building.

One day I was running an errand for her and on my way back cops were dragging her by the hair down the stairs — Bang! Bang! Bang! I got her groceries in my hand and she didn’t even see me, she was all bloodied up. I carry that today.

The Young Lords gave me an understanding of that. I remember being in the church later, listening to them speak, and that image came to me. I decided: We have to stop this.

FERNÁNDEZ: You’re articulating pretty brilliantly what I argue in the book — there’s something profoundly liberating for people, who’ve been told all their lives that they ain’t shit, to stand up. To do that knowing history, understanding how society works.

I grew up in the Bronx during the crack epidemic, aware that there was something wrong with the world, but not having the tools to figure out why. Somehow, I landed at Brown University in the 1990s. It’s an elite institution and they hire their first Latino Studies professor who teaches us about the Young Lords. I got so angry because I never knew about them. They’d been removed from public memory, amputated from the history that should be taught to young people in the Bronx.

Ultimately, I’d say that the children of migrants — especially from Latin America — connect more than anyone else with the history of the Young Lords. Because you wake up and all you see is death and abandoned buildings and you start believing what people and the media say about you. Then to see your own people take it and shred it and fight it in the streets — that’s freedom on a profound personal level. The Young Lords gave Puerto Ricans a big coming-out party through their militancy at that church.

SALDAÑA: They’d sit on the stoop with us and just talk, like we were in a classroom. Then we’d come together and say, “Man, what do you think, man? She’s saying some good stuff here.”

“So you going to stop selling drugs?”

“No, I ain’t gonna stop.”

Looking back, I had choices but I didn’t think I did. My pops, he drank too much, and my moms is on welfare. There were times when I was the only one bringing in money and I wasn’t willing to give that up. I finally understood what I was doing when somebody — I think it was Iris Morales — told me I was collaborating with my own oppression. That resonated. For the first time, I started developing a connection to history. Until then, everything was about daily survival. It took me awhile. I was arrested on weapons charges and possession of drugs.

So now I’m in a prison cell, reflecting on what I heard. Because I did become a member of the Lords — had they not touched my life, I would have continued poisoning my community, which is a terrible thing, or I would be dead. They saved me from a meaningless death. Because after that? If I was going to die, it wasn’t going to be meaningless.

FERNÁNDEZ: This brings up the concept of self-determination, the struggle of oppressed peoples to control our lives, collectively. In many ways, working to abolish prisons is the ultimate work in self-determination, because incarceration is the greatest site of un-freedom. American society uses prison to demonize people of color. Visiting Mumia Abu-Jamal in prison transformed me, because you get a sense of a whole country of human beings who’ve been thrown away.

So somehow I’ve been called to do prison work, which is not easy. It’s unforgiving.

SALDAÑA: In prison, I read about the history of Puerto Rico, the colonization by Europeans, how American Indians were annihilated, then those who resisted were put in prison for murder. You get to see prison as their tool to control us. But they’re in no moral position to give anybody a death-by-incarceration sentence.

Some people don’t agree with me, but in these times I think the greatest crime is mass incarceration. Who we going to hold responsible for that? There’s no individual crime, no matter how horrific, that equals it.

FERNÁNDEZ: But it’s healing to see yourself in this history — because the Young Lords actually won.

They’re credited with militant muckraking and press conferences publicizing how a third of East Harlem children tested lead-positive. They occupied the Department of Health, which embarrassed the mayor into passing anti-lead poison legislation. They occupied Lincoln Hospital, which led to building the new hospital, promised 10 years earlier. They drafted the first known Patient Bill of Rights. Their activism around sanitation led to many things, including more regular garbage pickup in East Harlem. The Lords are also important because they defended Puerto Rican political prisoners. In the late 1960s, here in New York, they raised up the names of independence leaders, like Pedro Albizu Campos.

SALDAÑA: In prison there was this guy, Carlito. He had a lot of time, I had a lot of time — we became real close. We was always saying to each other, “Listen, man, if you beat me out, I want you to do me one favor. Don’t send me no package. Just go to Puerto Rico, to old San Juan, where our revolutionaries like Don Pedro Albizu Campos and Doña Lolita Lebrón are buried. Take a picture and send it to me.”

Governor Cuomo actually granted Carlito a pardon, but I got paroled first. First thing I did when I got out, I went to Puerto Rico, took a picture, sent it to him. But before the bureaucracy could get Carlito out, he passed away. Seventy-five years old. Never got the picture. But that shows how touched people were by this movement.

You know, five or six years ago, I was still inside and I read an article in The Times that you was writing this Young Lords book. I thought that was so meaningful.

FERNÁNDEZ: Oh please. I’ve been working on this book since God was a boy –

SALDAÑA: I said, I should write this sister here, but I never did. And now — I never thought I’d be sitting in your apartment, discussing this book with you. I’m still in contact with other guys inside — they’re going to want this book.

FERNÁNDEZ: This may sound corny but, though I think it’s a rigorously researched book, I didn’t write it for my colleagues. I wrote it for the people the Young Lords were trying to organize.

SALDAÑA: Well, believe me, your book will do tremendous good. That book’s gonna travel.