The Metrograph cinema is hosting an impressive two-week, in-person series entitled Pioneers of Queer Cinema, described as, “A groundbreaking and extensive retrospective of American cinema celebrating the work of visionary queer filmmakers.”

The selections include many of the usual suspects, from avant-garde and experimental films by George Kuchar and Andy Warhol to New Queer Cinema favorites and more.

As a gay man whose worldview was shaped by many of the films and filmmakers on offer in this program, a handful of titles provided watershed moments in my life. These films were essential in forming my own understanding of LGBTQ life and identity — mine as well as others — so please indulge my trip down memory lane as I recall the various films from this program that I screened during impressionable times in my life.

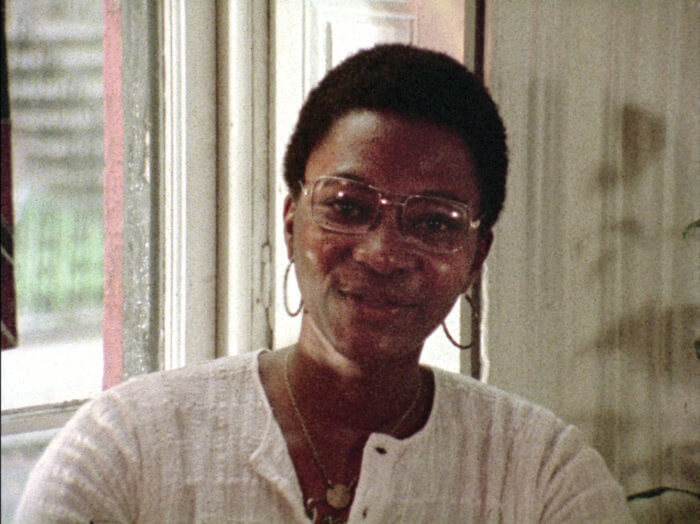

As a teenager, I remember hiding in a bedroom to watch the landmark documentary, “Word Is Out” (1977), which features poignant and emotional interviews with a cross-section of 26 members of the queer community who only had sexual orientation in common. I recall being eager to see what gay men (and women) looked like, and if and how I connected with them.

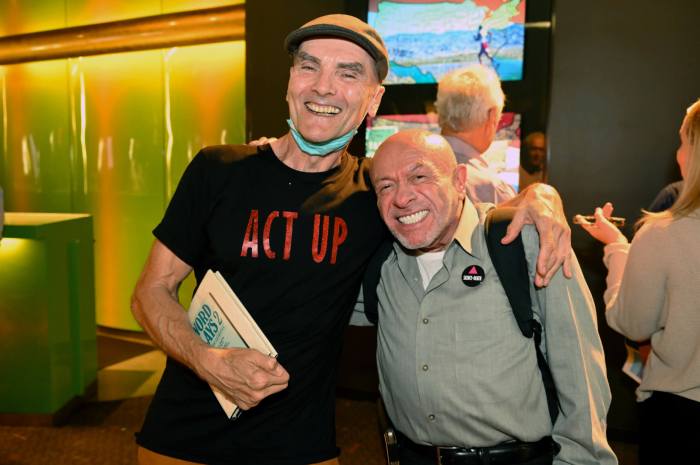

I re-watched Andrew Brown, Nancy Adair, and Rob Epstein’s remarkable documentary a few years ago and it was far more impactful for me as an adult — because of what its participants expressed and how the film depicted queer life in the mid-1970s, when being openly gay was less accepted than it is now. It is absolutely worth a look to see such positive representations back in the day and gauge how far we’ve come as a community.

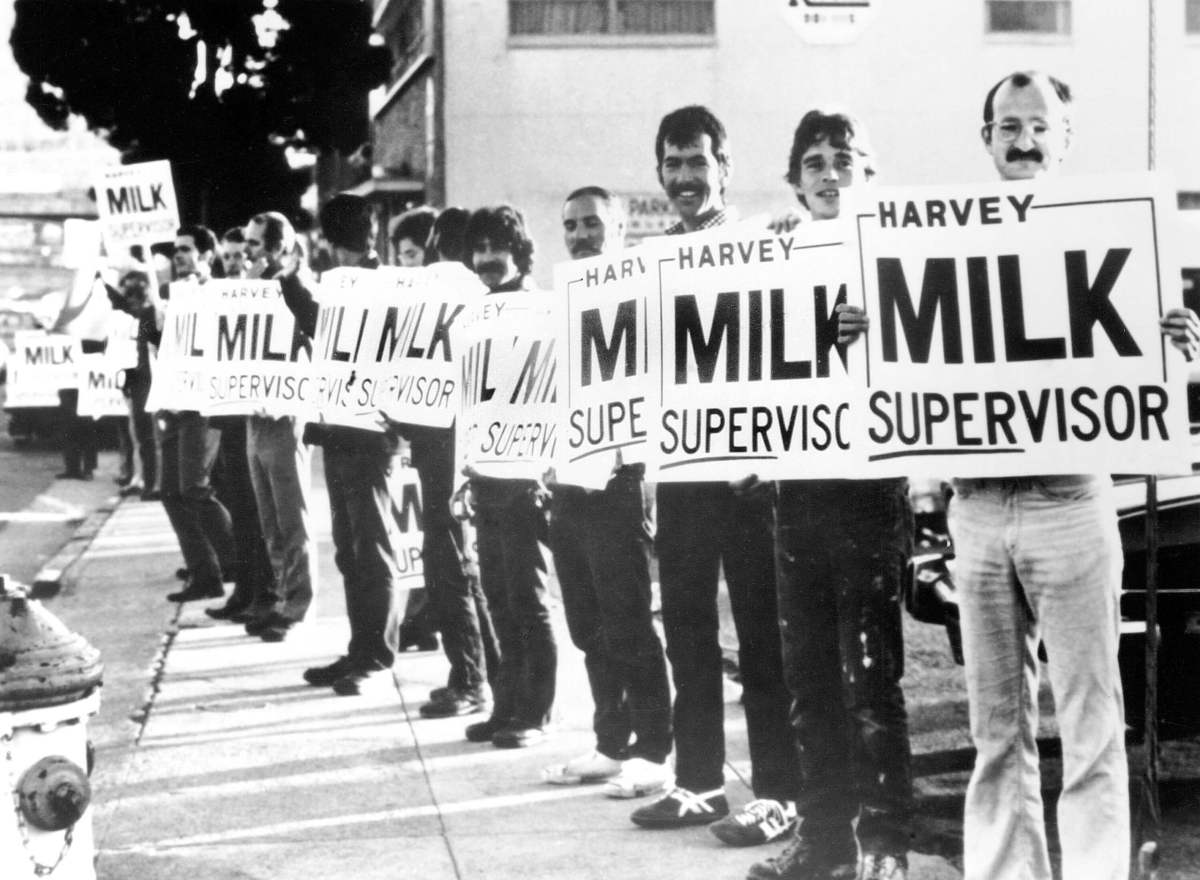

Epstein’s subsequent film, “The Times of Harvey Milk,” (1984) was even more inspiring. I recall seeing this documentary in Boston when I was 16 and closeted. I walked around the Orson Welles Cinema, a revival house, to get up the nerve to ask for a ticket to a gay film that I was excited to see. I even tried to convince the ticket seller that I was there for “The Purple Rose of Cairo,” which was on a split screen with “Harvey Milk.” Pretending I got the time wrong, I’ll just go see the documentary since I’m here. At least my anxiety was ameliorated as the film captivated me and sparked an interest in queer politics and activism. But as much as I appreciated Milk’s messages and the film itself, I didn’t come out until years after I saw it.

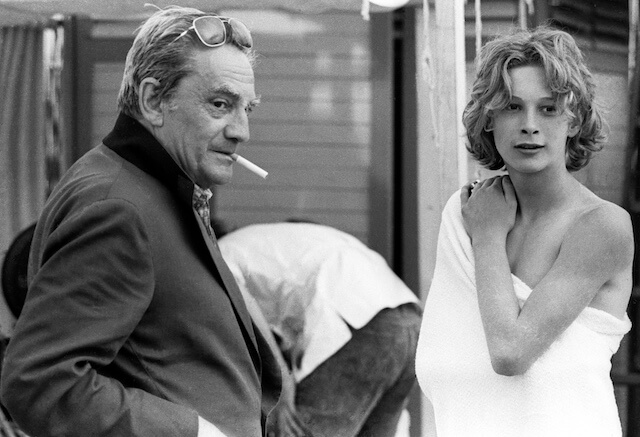

I did push the closet open a crack after seeing “Parting Glances,” (1986) Bill Sherwood’s only film and one of the first films to depict AIDS. I identify — then and now — way too much with the character of Michael (Richard Ganoung), who has a publishing job, a handsome blonde boyfriend, a coterie of great friends, and a dear (if alas, dying) best friend. It was kind of how I imagined my future life to be and, truth be told, pretty close to how my life turned out. I revisit this film from time to time, as it gives me such comfort.

Another film that gives me the feels every time I see it — albeit in a different way — is the new queer cinema classic, “The Living End” (1992), the breakthrough film by director Gregg Araki. This story of two HIV-positive guys who hit the road, and embark on a crime spree, was buoyed by an exciting, anarchic spirit and “F the World” attitude that gay men felt during the AIDS crisis given the Republican government’s treatment of the epidemic. The film is chock-full of (homo)erotic moments between the two leads, and the way Araki frames the guys’ faces touching makes the character’ intimacy is as palpable as their anger. “The Living End” spoke to my inner rebel and, like many viewers, I identified with Jon (Craig Gilmore), and crushed on Luc (Mike Dytri).

Three films screening at Pioneers of Queer Cinema showed me aspects of Black LGBTQ life that also enthralled me. I remember seeing Jennie Livingston’s extraordinary documentary, “Paris Is Burning,” (1990) with college friends upon theatrical release and being awed by this eye-opening immersion into the fabulous drag balls in New York. The film deftly shows how issues of race, class, and sexuality influenced the lives of these individuals who compete for “legendary” status by emulating the life and look of rich white people in America in underground ballroom circuit contests.

Likewise, Marlon Riggs’ remarkable, poetic “Tongues Untitled” (1989) astutely mixes spoken word, personal testimonies, and music to celebrate gay Black male identity, acknowledge racism, and even teach snap lessons, as it presents empowering voices of activism.

But one of my favorite New Queer Cinema films is Cheryl Dunye’s fabulous debut feature, “The Watermelon Woman” (1996). Dunye was the first out African American lesbian filmmaker to direct — as well as write, edit, and star in — a feature film. And what a film! This funny, sexy, scrappy, and very clever mix of fiction, documentary, and direct address considers identity politics, past, present, and future. Dunye directs herself as a young lesbian who makes a journey of self-discovery when she researches the life of Fae Richards, a fictional African-American actress who intrigues her. Set and shot in Philadelphia, Dunye clerks at a video store I frequented, and sets scenes in many of my favorite city haunts. But the point of Duyne’s film, which comes across beautifully, is that sometimes we have to search deeper into our own history, and sometimes we have to create it ourselves.

And this is what the Pioneers of Queer Cinema have done with their films. It may be why these features and documentaries have had such a lasting influence on me — and I suspect for many other viewers as well.

For a complete schedule of films and screening dates/times, visit https://metrograph.com/

“Pioneers of Queer Cinema” | The Metrograph | July 1-14