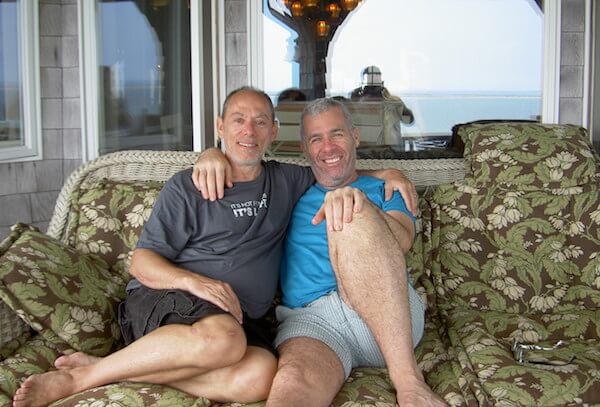

Alex Haiken and Mitchell Siegel, his partner of 10 years. | NATHAN DICAMILLO

If you tell Alex Haiken that he can’t be gay and Christian, you had better have done your homework.

“Because I’ve done mine,” he said. “And I say, ‘Come, let’s talk.’”

Haiken likes to talk. He was on the gay student union in college and spoke to classes about what it meant to be gay. Retired after a 23-year career at the UN, he spends much of his time volunteering and enjoying life in Manhattan with his partner of 10 years, Mitchell Siegel, but also devotes time as a former member of the ex-gay movement to talking with Christians online or in person about the importance of LGBTQ inclusion in the church.

RELIGION & GAY LIFE: Alex Haiken is a religious activist who found his way back to life as a gay man

Religion has always been a large part of Haiken’s life but not always an easy road. He grew up in a Reform Jewish household, but became Christian when he was 29. In his church, he gave up dating men until he reconciled his sexuality with his faith 16 years later. His journey has led him through several periods of acceptance and rejection.

“The Jewish community thinks I’ve turned my back on them because I’m a Jew who believes that Jesus is the Jewish Messiah,” he said. “Many Christians are not happy with me because I’m unapologetically gay, without secrecy or shame. And the secular gay community dismisses me as insane for my continued association with what they perceive to be a homophobic religion. So there aren’t many places I can go without pissing somebody off.”

Haiken grew up in the Reform Jewish tradition, went to Hebrew school, and was bar mitzvahed at age 13. But growing up, Haiken leaned towards atheism. Being Jewish for Haiken was more about the holidays, traditional food, and Yiddish expressions.

It was tales of life in a Jewish home that Haiken would tell Kevin Parker when they smoked weed together as young 20-somethings after working long shifts as waiters in a Manhattan restaurant. In response, Parker told Haiken that he was a “born-again Christian.”

Parker’s goal, however, wasn’t to bring a homosexual man to repentance. Parker grew up in a non-Christian home and followed in his brother’s footsteps when he became a Christian in the mid-‘70s.

“One of the things that’s great about Alex is that he’s a very, very caring person naturally,” Parker said. “When there was this essence of somebody else — God — who did things for us as a sacrifice, I think that touched him.”

Parker understood that Haiken had been in relationships with men since he was in high school. In fact, Haiken had fallen in love three times before becoming Christian. He came out to his parents at 22.

Parker didn’t tell his friend that he had to stop being openly gay to be Christian, but the teachings of many churches at the time emphasized that homosexuals who became Christians would have their heterosexuality restored to them by God.

“I believed that if this is the God who created the heavens and the earth then making me straight was small potatoes,” Haiken said. “It didn’t seem unreasonable.”

Haiken had seen some gay young men he knew grow up to remain homosexual in behavior and some grow up to be heterosexual in behavior. They were “just experimenting as kids,” in his understanding, and that made it seem all the more reasonable that sexuality might be mutable.

A year into his Christianity, Haiken found the ex-gay movement and was at first relieved to find people who loved God and were claiming that God could make them straight. The movement sought to liberate gay people from their homosexuality like Alcoholics Anonymous helping alcoholics be free of addiction, he believed.

“I thought, ‘What an answer to prayer,’” he said.

Haiken became involved with an ex-gay ministry in New York and enjoyed the sense of community that it provided him. He became suspicious of the movement’s validity, however, when he didn’t find his same-sex attraction changing even though his faith was not wavering.

“I did date a number of women but as wonderful as some of them were, it was always like a Christmas tree with a section of the lights out,” he said.

Haiken struggled more with his sexuality than the Christians who first taught him about Christianity.

“That was never ever, ever, ever a problem at all for me,” Carol Healey, the woman who gave Haiken his first Bible in 1982, said.

Healey’s Christianity began with a Catholic upbringing, but she says she “came to Jesus” when she was 40. After spending time in Baptist and non-denominational traditions, she is now Presbyterian.

“The kind of Jesus that I came to and the kind of Holy Spirit that I began to understand was a loving, caring, giving God,” Healey said. “One of the things I would say to people when they would criticize gays or that kind of thing, I said, ‘If Jesus was on earth, guess who he would be hanging out with? It wouldn’t be you or me, it would be them.’ That’s the thing that came to me so fully, was the mercy and the love of the Christ that I worship.”

Haiken’s reconciliation of his sexuality and faith didn’t come as easily as Healey’s acceptance of him. But his suspicion of the ex-gay movement led him down a new journey of biblical interpretation.

When Haiken looked into the historical context of what many call “the clobber passages” about homosexuality in the Bible, he found that they didn’t hold up to scrutiny. After 16 years of being a Christian, Haiken came to believe that homosexuality was compatible with Christianity just like heterosexuality was. He now understands that ancient biblical writers would have had no frame of reference for consensual, loving gay relationships.

When Haiken was in the ex-gay movement, he believed that his long time of being sexually active with men was part of why it was taking so long for God to make him straight. Haiken was a leader in the ex-gay movement and even gave his testimony on “The 700 Club,” Pat Robertson’s Christian television program. Over time, he realized that he wasn’t getting any straighter.

“It was horrible,” he recalled. “Like living a double life.”

When Haiken realized that straight men in his church were just as horny as the gay men he was counseling, Haiken soon began to realize that being gay wasn’t abnormal — it was just human.

“We had a men’s group,” he said. “One of the [straight] guys who was one of the pillars of the church said, ‘If it wasn’t for me being accountable to you, I would be out fucking everything that moves.’”

When Haiken left the ex-gay movement, he wrote apology letters to some of the men he used to counsel.

“I felt they needed to hear it from me,” he said. One of the women who led the ex-gay ministry still sends Haiken a birthday card every year. The first part of the letter wishes him a happy birthday, and the second half is always a plea for him to leave his homosexuality.

But he doesn’t spend much energy arguing with her.

“There is no functional reason for me to expect she will have a rational conversation,” he said. “You have to be discerning about who you talk to.”

Evangelicals in Haiken’s life loved that he was a Messianic Jew — one who accepts Jesus as their savior — while he was in the ex-gay movement.

“In fact, I found an inherent kind of pro-Semitism in some circles which I think can sometimes be as unhealthy as anti-Semitism,” he said. “But when I integrated my faith and sexuality, many in my evangelical community did a 180 and concluded they could no longer afford my friendship.”

Haiken compares the cost that LGBTQ people face in being accepted in the evangelical tradition with what would happen if a rabbi became Christian: a destroyed career and social standing.

“Christian leaders face similar losses in breaking with the traditional stance on homosexuality,” he said. “It’s remarkably analogous. Jews tried to tell me I couldn’t be both Jewish and Christian, and Christians tried to tell me I couldn’t be both Christian and gay.”

Haiken started dating again when he reconciled his faith and sexuality.

“Re-entering the dating scene in my 40s was frightening,” he said. “I felt like a nervous school kid learning to walk on new footing.”

When Haiken began to date again, his first relationship was with a Jewish man. He had minimal connection with Jewish people since he had become Christian, but found a deep connection with his second first love.

He now has that connection with Siegel, who also grew up Jewish and became Christian through dating Haiken.

“Mitch was this nice guy,” Haiken said. “Really upfront. What you see is what you get.”

Haiken went on to finish his master’s degree in Urban Ministry at Pennsylvania’s Westminster Theological Seminary in 2010 and continues to advocate for the acceptance of LGBTQ people in the church and in society. He sees setbacks with the Trump administration, but believes like Martin Luther King, Jr., that the arc of the moral universe is long but bends toward justice.

At jewishchristiangay.wordpress.com, Haiken writes about issues related to the LGBTQ community within the church. In one post from April 2011, he quotes evangelical scholar Lewis Smedes: “The Church’s treatment of homosexuality has become the greatest heresy in the history of the Church… It’s a living heresy because it’s treating God’s children as if they’re not God’s children.”

Haiken also works with the Trevor Project and uses his seminary degree to talk to gay youth who call the project’s hotline feeling that the Bible condemns them for who they are.

He seeks out communities that care about theology as much as he does but also understand his affirming position on homosexuality.

While he continues to receive opposition, some of his strongest opponents have become some of his strongest supporters through the years.

“I’ve learned that to live as a man of God and a follower of Christ means above all to live with personal integrity,” he said. “And I now get to live an honest and authentic life — before God, before man, and before myself. Unless we can be true to ourselves first, we cannot be true to anyone else. I think Shakespeare got it right when he said: ‘To thine own self be true, and it must follow as the night the day, thou canst not then be false to any man.’”