David Rothenberg.

BY ANDY HUMM | David Rothenberg has so many good stories to tell about his long life in entertainment, activism, politics, and working with ex-offenders that his friends made him write a memoir to get them all down. He has done just that in his wide-ranging “Fortune in My Eyes: A Memoir of Broadway Glamour, Social Justice, and Political Passion.”

The word “Fortune” in his title refers to a critical moment in his life –– when, in 1967, he produced “Fortune and Men’s Eyes,” an Off-Broadway play about prison life that led to after-show audience discussions, often with ex-offenders themselves appearing. Rothenberg went on to found the Fortune Society as a self-help group serving those released from prison get their lives back on track.

Rothenberg hosts the “Any Saturday” show Saturday mornings at 8 a.m. on WBAI-FM.

Rothenberg spoke to Gay City News the morning after the second presidential debate.

ANDY HUMM: You wrote a book about David Rothenberg. What did you learn about him that you didn’t know?

ANDY HUMM: You wrote a book about David Rothenberg. What did you learn about him that you didn’t know?

DAVID ROTHENBERG: I think what I learned is that you live your life and go through experience after experience and get through things and look back and realize that you are part of history. I learned about my role in gay history, Attica, in the historic meeting with the New York Times [regarding its lack of coverage of gay issues and people].

AH: You were once asked, “Rothenberg, are you a Jew?” Was that the first time you felt different?

DR:

AH: What happened in “All About Eve” to inspire you to want a life in the theater?

DR: I was in high school. I just thought when I saw it that there is a world beyond what I know. Bette Davis, Thelma Ritter, George Sanders. The lines, the cracks, the sophisticated talk. It was a world I wanted to be in. Who would have known I would have been working with Bette Davis ten years later?

I used to find Vito Russo in demos and we talked old movies. While others were chanting, “They say, ‘Get back,’ we say, ‘Fight back!’” Vito said, ‘You know what a real injustice is, Thelma Ritter getting eight nominations and never getting an Oscar.’”

You can be involved in serious issues about people coming out of prison or AIDS and find humor. While you’re fighting, you can still find the absurdity in life. On the other hand, when I saw “How to Survive a Plague,” and saw Vito with tubes coming out of his face, I had to leave. Vito was wonderful, so bright.

AH: Who was your favorite client as a press agent?

DR: Loved working with the guys from “Beyond the Fringe” — Alan Bennett, Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, and Jonathan Miller. They were unknown then. We were all the same age. More like friends. They were smart and funny and politically very hip. Also liked working with Ladysmith Black Mambazo, the South African group, on “The Song of Jacob Zulu.” I had always had a stereotype from the movies of the Zulu as fierce warriors, and here were these gentle, kind men. Invited me for a Zulu feast.

Linda Lavin has become a lifelong friend. I loved an actress named Kate Reid, who did the matinees of the original “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” and was Linda Loman to Dustin Hoffman’s Willy. And Joy Behar was tremendous fun to work with, and I enjoy her friendship now.

AH: And your worst experience as a press agent?

DR:

AH: What’s the best thing about the theater now?

DR:

Best thing now is taking a young person from Fortune. Went to “Bring It On” with a 22-year-old from Camden. Watching his joy in discovering this was like recalling what it was like for me discovering theater. He said, “You could almost lean over and touch them. “ It’s a great way to go to the theater. My theater friends walk in with that “prove-it-to me” puss.

AH: Worst thing?

DR: The prices. It’s the same in sports. At the Yankee playoff game, there were 3,000 empty seats. They’ve priced themselves out because they’ve pigged out.

AH: You went from Broadway to helping ex-offenders. We know that this was due to producing the play “Fortune and Men’s Eyes” and hearing from ex-offenders. But what was it within you that was struck to make such a radical change in your life?

DR: The ‘60s was a time when I was involved in the civil rights movement and became aware of inequities based on race. I was impressed with the humanity of ex-offenders. They were struggling to make it and barriers were overwhelming –– jobs, housing, and just being honest about who they are.

AH: You were called into the Attica prison uprising. What’s gotten better about the way we as New Yorkers treat prisoners and ex-offenders?

DR: Not much. There’s overcrowding. We’re locking up too many people. I ask people at Fortune, “Did you have spiritual guidance in prison?” They tell me, “They destroyed my spirit.” Prisons are environments of negativity. The whole concept of isolating people is counterproductive.

The Quakers got people out of stocks into a room where people do penance — thus the “penitentiary.” It’s death by boredom on Rikers. Your problem is never confronted. To survive you have to perform acts that get you into prison. “I’ll get back at you all,” one character in “Fortune and Men’s Eyes” says. The Fortune Society tries to undo the damage. Parole says get a job. You have to learn how to function first.

There is no constituency for prison reform. People say, “What about the victim?” But the answer is giving people a hint that there is something else in life. Caz Torres, an ex-offender who was in our play, “The Castle,” said when he was the age of ten, “I discovered weed and wine, and that’s how I managed my pain. I grew up angry. Don’t know why. Stole for drugs.”

I’ve been to Central American prisons and European prisons and those in the US. They are all exercises in institutional futility. If you put a snake in a box and jab it every two minutes, you think it is going to come out passive?

AH: What most needs to be changed?

DR: Family planning, family support, the school system. When the crime rate went down 15 or 16 years after Roe v. Wade, I noted that before the “Freakonomics” guys did. People said, “It sounds like genocide,” but it was just a fact. Many are men who were unwanted as babies. Meeting at the Castle [Fortune’s center], a guy wanted to make contact with his father. He needed a support system to do it. He talked about his experiences about being abused as children. One big tough guy said, “I wish I had a father I could get back together with.” They talk about things they had never gotten out and get rid of their pain.

AH: You were one of the few prominent people to come out in the early 1970s and appear on TV to talk about it on shows such as “David Susskind.” How did that change your life?

DR: I stopped lying to everyone. I always thought I was an honest person until I realized I was lying to everyone in my life. I told my mother I was going “out,” not where I was going. Telling the truth is so much easier. When you lie, you can’t remember what you told people.

AH: What’s your proudest achievement as a gay activist?

DR: I guess when I was talked into running for City Council [in 1985] and running a serious campaign. It created an atmosphere for other gay people to consider. Run into all kinds of people like Tom Duane and Deborah Glick and Chris Quinn, and they say it was the first campaign they got involved in because they thought if it was possible for them. We’d had symbolic gay campaigns before, but this one raised money and had possibility. To campaign in Penn South and knock on a door and see Bayard Rustin, and he knew who I was and that he’s voting for me — that was something.

AH: Anyone you admire in politics today?

DR:

I like Barack Obama. He was wonderful in the debate last night. Brings dignity to the position of the president. My heroes were Eleanor Roosevelt, Adlai Stevenson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Mahatma Gandhi — pacifist fighters.

AH: As a city human rights commissioner in the 1980s, you challenged anti-gay religious leaders for the way their condemnations of gay people gave license to disturbed people to hurt us. Is religion getting better or worse about homosexuality?

DR: We‘ve done legislation and psychology, but work needs to be done on the churches that are so hypocritical and so judgmental and negative and mean.

AH: What’s your take on the LGBT movement today, and what do you feel most needs to be done still?

DR:

But there’s no sense of gay history. I was in the Center last night and remembered being on the original board. We met three to five nights a week. The young people don’t know about any of that. But you can’t sit around waiting for applause.

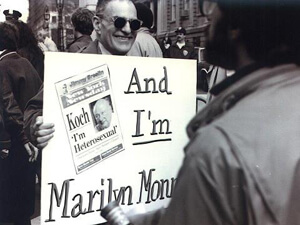

AH: Do you hope Ed Koch comes out publicly or would it be better at this point if he died in the closet?

DR: Who cares at this point? He’s just another pretty face. He has to live with himself, and I’m sure it is not easy.

AH: Tell us something good about approaching 80?

DR: If you have a problem about getting older, hang out with some young people. Take a young person to the theater. It makes it a lot of fun.

King, Gandhi, Beethoven all died, and I’ll die –– and the world will go on without me.

FORTUNE IN MY EYES: A Memoir of Broadway Glamour, Social Justice, and Political Passion | By David Rothenberg | Applause Theatre & Cinema Books | $29.99 | 320 pages