A 1995 documentary about German-born singer Nico, whose real name was Christa Päffgen, is titled “Nico Icon.” Italian director Susanna Nicchiarelli’s narrative film “Nico, 1988” pulls her off that pedestal and turns her back into a human being. Nico’s 15-year period of heroin addiction and status as a beautiful woman who acted in Fellini and Warhol films and sang with the Velvet Underground have both long been romanticized. One of the achievements of “Nico, 1988” is showing that touring clubs holding 200 people for most of the year in order to make a living while having to shoot heroin into one’s foot is a major bore.

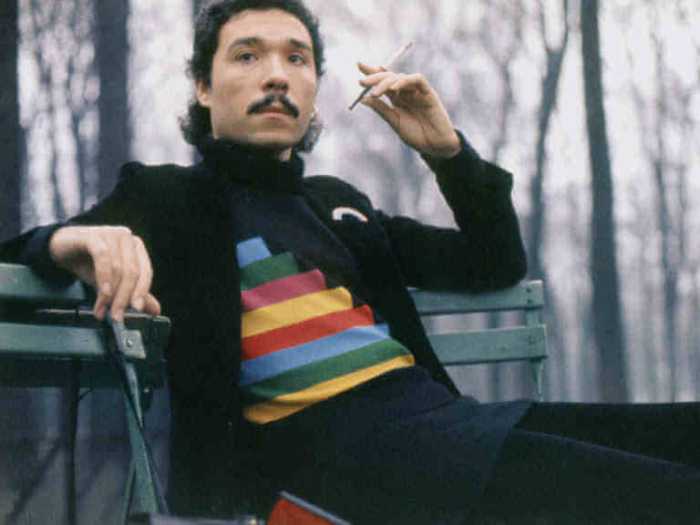

Danish actress Trine Dyrholm plays Nico, doing her own singing. Living in Manchester in 1986, her new manager Richard (John Gordon Sinclair) gets her to tour Europe to promote her album “Camera Obscura,” released the previous year. She agrees, playing with a pickup band whose guitarist’s own drug habit causes problems. Along the way, she tries to resurrect her connection with her son Ari (Sandor Funtek), of whom she lost custody. The title refers to the year of Nico’s death; the film fills in her final two years and six months of life.

Nico had enough talent and charisma that the Velvet Underground’s 1967 debut album is named “The Velvet Underground and Nico” even though she only sings three of its songs. She began the 1960s with a brief appearance in Fellini’s “La Dolce Vita” and acted in several Warhol films, with him devoting an entire reel of “Chelsea Girls” to her. She returned the favor by naming her debut solo album after the film; however, it pursued a heavily orchestrated pop style (with the exception of the feedback-driven “It Was A Pleasure Then,” which sounds like a Velvet Underground outtake) that she would never again show interest in.

Starting with her next album, “The Marble Index,” Nico abandoned conventional pop and rock music in favor of intense dirges driven by her harmonium playing and accented monotone voice. She became addicted to heroin in the early 1970s, in the company of filmmaker Philippe Garrel — her album “Desertshore” supplies the soundtrack to his best film, “The Inner Scar” — and that wrecked whatever career momentum she had. She lived to be 49 but only recorded six studio albums.

Throughout “Nico, 1988,” she is interviewed by men who ask about the Velvet Underground and the 1960s, while she insists on talking about her current music instead. She couldn’t have known it, but when the film begins in 1986, she had already released her last studio album. Only one scene, at an illegal show in Prague that gets busted by the military, shows her performing to an appreciative audience. The rest of the film depicts her enjoying playing music, but always in rehearsal settings. Richard seems very un-rock’n’roll, sporting a graying crew cut, mustache, and blazer, always standing around with a vague look of disapproval.

The one aspect of “Nico, 1988” that really doesn’t work is its use of flashbacks aping various film styles: documentary footage of World War II representing Nico’s childhood and really clumsy copies of 1960s avant-garde films a la Warhol. This film does not use a note of Nico’s actual music; instead, Dyrholm did her own singing backed by the Italian rock band Il Grande Freddo. Dyrholm does not look like the blonde, pretty Nico that most people remember from her appearances in Garrel and Warhol films. In this film, Nico is in her late 40s, and journalists started noting in the late 1970s that she was beginning to put on substantial weight. Nicchiarelli has written that she wants to embrace Nico’s “fat and ugly” period. Her approach to female middle age is extremely respectful; however, given the real-life Ari’s claim that Nico introduced him to heroin and reports of racist and anti-Semitic comments and behavior from her, the film’s depiction of her seems sanitized. Here, her guitarist is black and her manager is Jewish.

Given the role drugs play in Nico’s mythology, many people falsely assume that she died of an OD. There are several stories about how she actually died in the summer of 1988, but she apparently either had a heart attack or was hit by a car while riding a bike in Spain. “Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami” director Sophie Fiennes has expressed anger at the way films about female musicians so often center on their addictions and self-destruction. As this film depicts, Nico actually entered a methadone program shortly before her death.

Maybe the biggest achievement of “Nico, 1988” is showing a woman struggling to retain her dignity and making a living under difficult but not impossible circumstances, instead of suggesting there was anything cool about Nico’s gradual decline. Paradoxically, this film’s Nico is a survivor who died before her time.

____

NICO, 1988 | Directed by Susanna Nicchiarelli | Magnolia Pictures | Opens Aug. 1 | Film Forum, 34 W. 13th St. | filmforum.com