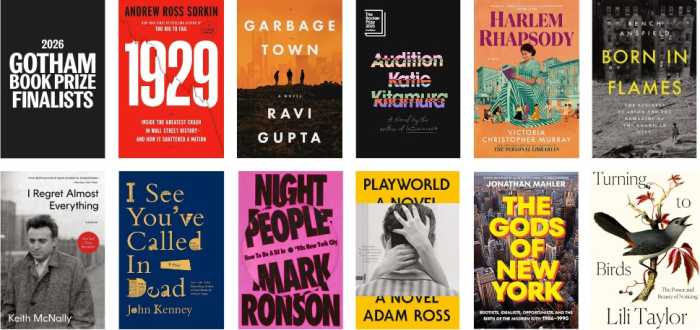

Nathan Gunn and Renée Fleming in the Susan Stroman production of Franz Lehár’s 1905 “The Merry Widow” at the Metropolitan Opera. | KEN HOWARD/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

Franz Lehár in his 1905 operetta masterpiece “The Merry Widow” used the waltz as a metaphor for the push and pull of sexual attraction. Money and politics push the ex-lovers Hanna Glawari and Count Danilo apart but the strains of the waltz pull them together. Eventually politics and money capitulate before the power of music and love.

On New Year’s Eve, the Metropolitan Opera unveiled its second production of Lehár’s masterpiece, directed and choreographed by Broadway’s Susan Stroman (“The Producers”) in her first operatic assignment. Renée Fleming and Nathan Gunn star as the sparring, waltzing former and future lovers. Also making a Met debut was darling of Broadway Kelli O’Hara in the secondary soubrette role of Valencienne, with Sir Thomas Allen and Alek Shrader as the men in her life. With two glamorous opera stars experienced in crossover in the leads, sumptuous Belle Époque scenery by Julian Crouch and lavish period costumes by William Ivey Long, a relatively restrained book and lyrics translated by Jeremy Sams, all guided by Tony winner Stroman’s knowing hand, this “Widow” seemed destined to be a surefire hit.

Unfortunately, it hit the palate like yesterday’s champagne without the bubbles and offering no kick. It looked new and pretty but felt slightly arthritic and tired. The missing ingredients were essential ones — sexual chemistry and the thrill of the dance. Fleming and Gunn are slightly younger and more agile than Frederica Von Stade and Placido Domingo were in 2000 when they starred in the Met’s premiere production of “The Merry Widow.” But they dance less and strike fewer romantic sparks, Stroman’s production being much more conservative and old-fashioned than the Tim Albery production it replaces.

Led by Fleming and Gunn, Stroman’s Met “Merry Widow” production lacked fizz

The problem was not with the diva. Fleming looked lovely and youthful enough — her hourglass figure poured into Long’s silk gowns — and seemed game for anything. She even handled her spoken lines with some flair (helped by her recent sojourn into straight dramatic acting; “Living on Love” is scheduled to transfer to Broadway this April).

In Act I, Fleming’s middle voice sounded swallowed along with most of her words and her top was uncharacteristically tentative. In Acts II and III, she warmed up nicely — her signature tonal mix of silver and cream suiting the Viennese style perfectly. Fleming soared through the interpolated “Liebe du Himmel auf Erden” (from Lehár’s “Paganini”) in Act III. But when she was supposed to be swept away by the irresistible strains of the waltz, Nathan Gunn’s bland, personality-challenged Danilo did a measly two-step that hardly traveled across the floor — no turns, no twirls, and a feeble final dip without passion.

“Dancing With the Stars”’ Maksim Chmerkovskiy probably can’t sing but he definitely would have swept Fleming off her feet while suggesting what’s in store when the dance is over. Gunn was more suburban husband than dashing rake — looking a little softer in the middle, the erstwhile barihunk didn’t even wear his tails and military uniform with flair. His salon baritone did the job decently but, as in everything else he did, lacked sparkle. The dialogue scenes between the leads also lacked sexual tension and humor. Fleming is by nature rather demure onstage; she needs a strong leading man to draw her out.

The other romantic pair seemed mismatched, as well. O’Hara showed off impressive legit soprano chops — not surprising since she has a degree in opera from Oklahoma City University and even participated in the Metropolitan Opera Regional Council Auditions. She kicked up her heels gamely in Act III’s grisette can-can number and showed the rest of the cast how to put over lyrics with intelligibility and pizzazz. She certainly showed greater vocal and dramatic authority than Shrader’s Camille de Rosillon, who looked almost prettier than her but whose acting was as stiff and tentative as his tight, shakily produced lyric tenor. His vocal stiffness, iffy top, and lack of charm fatally compromised the ravishing “Pavilion Duet” in Act II.

As Valencienne’s befuddled husband Baron Mirko Zeta, Allen stole every scene he was in. He easily could have had a successful career as a dramatic actor. Margaret Lattimore also stole scenes as the bitchy matron Praskowia, but Carson Elrod was directed to play Njegus as the sassy gay friend. He got easy laughs but they were incongruously at the expense of the tone and period sensibility.

Stroman’s production numbers at the top of Acts II and III were efficient and diverting but lacked imagination. The shallow Act I embassy set precluded much in the way of dancing and the dramatic pacing was off, with dead space between lines and entrances and exits as well as jokes that failed to land. Acts II and III (played together without intermission) had better rhythm and managed to work up some dramatic momentum.

Sir Andrew Davis’ elegant baton brought a wistful autumnal touch of “Der Rosenkavalier” to Lehár’s fizzy score — Act II’s “Women” march lacked rhythmic swagger and martial strut while the Act III grisettes' can-can needed more giddy abandon. With a dashing, dancing, dangerous leading man, better pacing, better dances, and a hint of sex, this could be a very good show. All the other ingredients are in place.

Perhaps Susan Graham and Rod Gilfry will be lighter of step and quicker of pulse when the “Widow” returns in April. The current “Merry Widow” will be broadcast Live in HD on January 17.