The Nevada Supreme Court ruled that the US Supreme Court’s 2015 marriage decision should be applied retroactively when divvying up assets in divorce cases.

The ruling was prompted by a divorce case involving two Nevada women who were married in Canada in 2003, but subsequently broke up and became embroiled in a dispute over their belongings.

Marriage equality for same-sex couples came to Nevada late in 2014 when the US Supreme Court refused to review a decision by the San Francisco-based Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals holding that the state’s ban on such marriages was unconstitutional. This decision came after Mary Elizabeth LaFrance and Gail Cline had decided to end the marriage that their state had never recognized, but their legal proceeding to dissolve the marriage provided the vehicle for Nevada’s Supreme Court to rule unanimously on December 23 that the marriage these women contracted in Canada in 2003 must be recognized as of the time they were married.

The women, who are longtime Nevada residents, had gone to Vermont in 2000 to form a civil union under that state’s newly passed law — the first in the nation to establish a legally-recognized status for same-sex couples. They then went back home to Nevada, where their civil union did not have any legal standing.

When same-sex marriages first became available in Canada in 2003, they went there and got married, again returning home to Nevada where their marriage was not recognized. Although Nevada later enacted a registration process for domestic partnerships and the women could have registered their Vermont civil union for some limited state recognition, they failed to do so. By the time Nevada began to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples in 2014, these women were ending their relationship and in no mood to get married.

There is no question that a Nevada court has the authority to recognize their Canadian marriage for purposes of formally dissolving it, but a sticking point in the case was how to divide up the assets of their marriage. Nevada is a “community property” state where anything acquired by either spouse during a marriage is presumed to be “marital property,” subject to being divided up between them upon a divorce. This rule does not apply to property that is explicitly identified as property of one of the parties at the time it is acquired. Otherwise, everything goes into the pot to be divvied up.

Here’s where things got contentious in the LaFrance-Cline divorce. When did their “marital community” start, for purposes of deciding what is marital property?

Cline asked the trial court to accept 2000 as the starting date based on their Vermont Civil Union, and Clark County District Court Judge Mathew Harter agreed. LaFrance appealed, arguing that Nevada had never recognized their Vermont civil union as a marriage or even as a legally recognized status, that they had conducted their relationship assuming that each was the owner of anything that individual acquired, and that 2014, the date Nevada was required by court order to recognize same-sex marriages, should be the relevant date for recognizing them as being married.

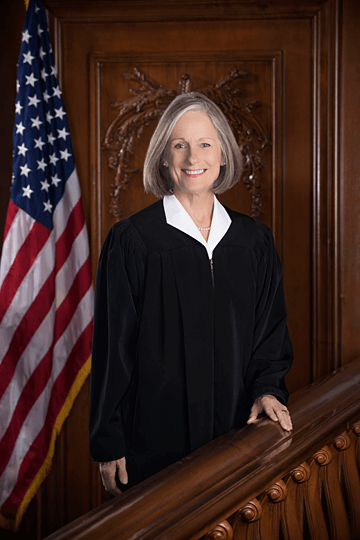

The Nevada Supreme Court decided that neither Judge Harter nor LaFrance was correct. Chief Justice Kristina Pickering wrote for the court that the US Supreme Court’s 2015 marriage equality decision, Obergefell v. Hodges, should be retroactively applied to recognize the 2003 Canadian marriage as the start of the parties’ “marital community.”

The Supreme Court’s rulings interpreting the U.S. Constitution are frequently applied retroactively when they are interpreting old constitutional provisions. In this case, the 14th Amendment, which was added to the Constitution after the Civil War in 1868, provided the basis for the Court’s ruling that same-sex couples have the same right as different sex couples to marry and to have their out-of-state marriages recognized by their home state. Although a marital right for same-sex couples had never previously been recognized by the Supreme Court, it theoretically existed from the moment the 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868, requiring all states to provide equal protection of the laws to all their citizens and recognizing their fundamental rights, including the right to marry.

However, the Obergefell decision applies only to marriages. Civil unions did not exist in the United States until Vermont’s statute was enacted in 2000, and they are not marriages. On the other hand, Canadian marriages have traditionally been recognized by courts in the United States. The Nevada Supreme Court concluded that when LaFrance and Cline married in Canada in 2003 and returned home to Nevada, their marriage was entitled to be recognized at that time, and for purposes of community property, this “marital community” began in 2003.

LaFrance protested that this was unfair, arguing that she and Cline had been operating all these years under the assumption that they did not have any legal rights as a couple in Nevada throughout the period of their Canadian marriage, but that argument did not sway the court.

“Nevada must credit the parties’ marriage as having taken place in 2003 and apply the same terms and conditions as accorded to opposite-sex spouses,” wrote Chief Justice Pickering. “These conditions include a presumption that any property acquired during the marriage is community property and an opportunity for spouses to rebut this presumption by showing by clear and certain proof that specific property is separate.”

Consequently, the property division issue was sent back to Judge Harter “to apply community property principles to the parties’ property acquired after their 2003 Canadian marriage.”

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.