In a sharp change of course, Nevada’s governor and attorney general announced on February 10 they would not defend the state’s ban on same-sex marriage in a case pending before a federal appeals court. A US district court earlier upheld that ban, and an appeal by Lambda Legal on behalf of eight plaintiff couples is now before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, based in San Francisco.

This turn of events has an interesting backstory.

On January 21, State Attorney General Catherine Cortez Masto, a Democrat, filed a brief responding to the plaintiffs’ arguments on appeal. In late 2012, District Court Judge Robert C. Jones found that Nevada had a “rational basis” for denying same-sex couples the right to marry. He also wrote that the US Supreme Court’s refusal in 1972 to hear an appeal from a Minnesota gay couple seeking the right to marry, finding there was no “substantial federal question” at stake bound him to not rule for the plaintiffs.

GOP governor, Democratic attorney general agree 2002 amendment can’t survive tougher judicial review standard

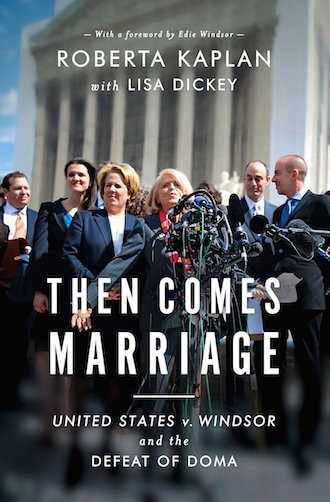

In her January brief, Masto challenged the plaintiffs’ contention that the state’s ban had no rational basis and was purely discriminatory and that last year’s Supreme Court ruling in the Defense of Marriage Act case rendered the 1972 court action in the Minnesota case moot.

The very same day Masto filed her brief, however, a three-judge appellate panel of the Ninth Circuit, in a case involving a pharmaceutical company’s “peremptory challenge” to a gay juror hearing an antitrust lawsuit regarding AIDS medication pricing, ruled that claims of sexual orientation discrimination must be subjected to “heightened scrutiny,” a tougher level of judicial review that the “rational basis” test Judge Jones applied in the Nevada marriage case.

Under a “heightened scrutiny” standard, a discriminatory policy is presumed to be unconstitutional unless the state can show it substantially advances an important government interest. Most legal observers agree that same-sex marriage bans cannot survive such scrutiny.

A few days after the Ninth Circuit’s ruling in the gay juror case, Masto announced she was considering withdrawing her brief in the marriage case, and after several days’ discussion with Republican Governor Brian Sandoval, she moved to do so, a decision the Ninth Circuit accepted. Both Sandoval and Masto agreed the marriage ban was not defensible given that the Ninth Circuit had established heightened scrutiny as the standard of review for gay discrimination claims.

Defense of Nevada’s ban on same-sex marriage is now left to the Coalition for the Protection of Marriage, a conservative organization that backed the anti-gay constitutional amendment enacted in 2002. That group’s brief focused on arguments, discredited by research, about the best circumstances for raising children and predicted, in essence, the collapse of civilization as we know it if same-sex couples are allowed to marry.

Nevada’s withdrawal from the case leaves the tantalizing possibility that a Ninth Circuit ruling in favor of the plaintiffs would go no further, since the Coalition for the Protection of Marriage –– like the group that defended California’s Proposition 8 –– clearly would not have constitutional “standing” to seek Supreme Court review.

That’s an ironic outcome, since it’s not a certainty that Nevada would fail if it chose to defend its marriage ban before the Supreme Court. The Ninth Circuit may now be applying “heightened scrutiny” in gay discrimination cases, but the Supreme Court, in last year’s DOMA ruling, did not say it was using that same standard. The Ninth Circuit's gay juror decision concluded that “heightened scrutiny” was in fact at the heart of the DOMA decision. If the Nevada ban is struck down by the Ninth Circuit, it’s certainly possible that Governor Sandoval –– who is a Republican, after all –– would conclude the state should petition the Supreme Court with the argument that heightened scrutiny was not the correct standard in this case.

One other twist in this case is that the Ninth Circuit has given Abbott Laboratories, the defendant in the gay juror case, 90 days to petition for a rehearing by a larger appellate panel. If such a petition were granted, the heightened scrutiny standard used in that case would be suspended and therefore not binding on a different appellate panel if it heard the marriage case during that period. So the timing in the two cases is also a factor.

The plaintiffs and organizations filing briefs in support of them have until February 25 to reply to the Coalition’s brief. At that point, the schedule for oral arguments will be announced, though the Ninth Circuit has already accepted Lambda's motion for expedited hearing in the case.

In other pending marriage suits, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver will hear oral arguments in the Utah case on April 10 and in the Oklahoma case on April 17. A ruling by the federal district court in Norfolk, Virginia on a marriage equality case there is expected soon, so there may also soon be an appeal pending in the Richmond-based Fourth Circuit. And, there is already an appeal before the Cincinnati-based Sixth Circuit in a case where the district court ordered Ohio to recognize an out-of-state same-sex marriage for purposes of approving data on a death certificate. Finally, a district court judge in Kentucky on February 12 struck down that state's ban on recognition of legal same-sex marriages performed elsewhere.

It’s likely, then, that sometime during 2014 federal appeals court rulings on marriage equality will have disappointed parties knocking on the Supreme Court’s door. The high court will likely find it needs to open the door and accept one or more cases for review.