The new Netflix documentary on United Kingdom-based gay human rights activist Peter Tatchell is a breathless 90-minute trip through just some of the great man’s 54 years of fearless activism on behalf of LGBTQ people and all those oppressed by dictators and bigots.

Tatchell’s most famous direct actions are documented: He took the pulpit from the Archbishop of Canterbury in his cathedral on Easter Sunday 1998 to decry Anglican opposition to legal gay relationships; exposed homophobic, hypocritical gay bishops in a pair of confrontations that brought him lots of hate; and made two attempts at a citizen’s arrest of Zimbabwean strongman Robert Mugabe, turning Tatchell into a national hero after he risked getting run over by Mugabe’s car and wound up getting beaten while shouting out the late president’s crimes against humanity.

Tatchell even takes on Queen Elizabeth II, urging her through a bullhorn to “stop homophobia in the Commonwealth!” as she walked to a meeting of the Commonwealth nations she so values, many of which still criminalize gay sex under laws imposed when they were UK colonies.

Gay singer Tom Robinson, who has seen Tatchell in action for decades, calls him a “brave mother******.” Archbishop George Carey calls him “a bullying kind of chap.”

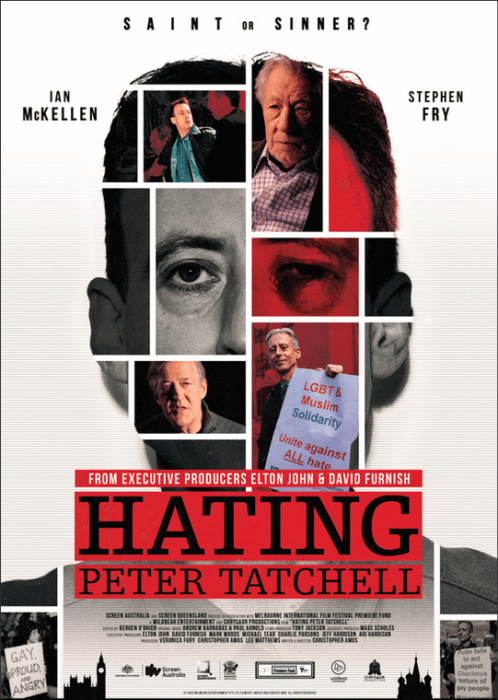

Tatchell is aided in telling his story by two gay national treasures: Ian McKellen, who interviews him throughout, and Stephen Fry, who offers commentary, praising him at the outset for his “extraordinary contributions to the happiness of millions who never heard of him.”

Fry, who played Oscar Wilde on film, tips his hat to Tatchell as “a performance artist” who always knows how to get into the spotlight to put an image and a message across. Elton John, who executive produced the documentary with his husband, David Furnish, praises Tatchell’s “bravery and courage.” McKellen, Fry, and John are celebrated performers but they are also gay and AIDS activists in their own right and know from whence they speak.

This is the feature documentary debut for director Christopher Amos, who produced the drag documentary “Dressed as a Girl” and who, like Tatchell, is Australian British. He is a veteran LGBTQ journalist, activist, and filmmaker and takes us back to Tatchell’s youth in Melbourne, the stepson of a fundamentalist mom and a brutal stepfather who beat him often and instilled in him a lifelong hatred of bullies.

Tatchell was deeply affected at age 11 by the murder of four little girls by white supremacists in Birmingham, Alabama in 1964, and he modeled his own fights for justice on the US civil rights movement.

As a student, he was active in the raucous protests against Australian involvement in the Vietnam War and left for Britain in 1971 so as not to be drafted into that immoral conflict.

At 19, he arrived in London, where men could be arrested for kissing each other good night and where other aspects of gay male life were still unlawful, given the very partial decriminalization of 1967. He threw himself into the Gay Liberation Front, helped organize the UK’s first Pride march in ’72, and went to East Berlin to raise gay issues at the World Festival of Youth in ’73 as he saw ours as a global movement.

He got a real taste of backlash when he was Labour’s candidate for Parliament for the Bermondsey constituency in 1983. His Liberal Party opponent used his homosexuality against him and crushed Tatchell at the polls. Undaunted, it made him fight harder for gay rights and against the burgeoning AIDS crisis in Britain that was compounded by the anti-gay bigotry of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, whose infamous Section 28 banned mentioning gay issues in schools.

Tatchell helped the group OutRage! to organize direct actions against Section 28, the ban on gays in the military, police entrapment, and a spike in anti-gay violence — as well as as challenging the ban on same-sex marriage from 1992.

We hear disagreements on tactics from insiders such as Angela Mason of the Stonewall group (like our Human Rights Campaign) and Chris Smith, the first out gay MP. There is footage of David Hope, a bishop he urged to come out, and audiences and panelists on talk shows ripping into Tatchell on that issue and for “intruding” on the Canterbury Easter service. Unbowed, Tatchell shoots back, saying, “It is a bit rich for the church to talk about ‘intrusions’ when they have been intruding on the lives of lesbian and gay people [for centuries], saying we’re sick and immoral and going to burn in hell.” Tatchell got used to being called “counterproductive” and says the same condemnations were leveled at suffragettes and civil rights activists.

Disclosure: I hosted Peter Tatchell on a visit to New York once and he gives me some of his precious time when I visit London. Walking with Tatchell is an experience, stopping by a weekly demonstration of Ugandan activists working for justice in their homeland that he and his Peter Tatchell Foundation supports, and seeing him being surrounded by love. He showed me where he was detained at an old Covent Garden police station in a cell guards told him had held Oscar Wilde after his arrest in 1895. And we were once outside the Old Vic Theatre when a well-dressed businessman stopped him and said with deep appreciation, “I just want to shake your hand.”

As the film shows, such mainstream approval of his work was hard to come by early on. “Someone said you were the most hated person in Britain,” McKellen says. Boxer Mike Tyson has some choice words for him when confronted about his homophobia by Tatchell. Demonstrating in solidarity with Russian gay activists, Tatchell gets bashed in the head hard by counter-demonstrators. These blows — and more than 50 attacks on his flat — have taken their toll, but he never backs down.

For all his courage and conviction, Tatchell confesses to “quite debilitating self-doubt” and dread at getting arrested and beaten up again on a return trip to Moscow to call attention to Putin’s failure to stop the state murders of gay people in Chechnya. But he soldiers on: “I’m the kind of person who never feels satisfied. I’m always thinking, ‘What’s next?’” All this nuance adds to the richness of the portrayal.

While most all of Tatchell’s actions are gripping and instructive, the film is also graced with moving codas with his mother and re-assessments half a century on by some of the people he tangled with, including Archbishop Carey.

“I love people,” says Tatchell, now 69. “I love freedom, equality, and justice and that’s what drives me forward. I don’t like to see people suffering.”

“Hating Peter Tatchell” is required viewing for activists, but there is a personal story in there that ought to compel even the apolitical as we witness him grow into a national treasure himself. He works far too long and hard, but there is no stopping him.