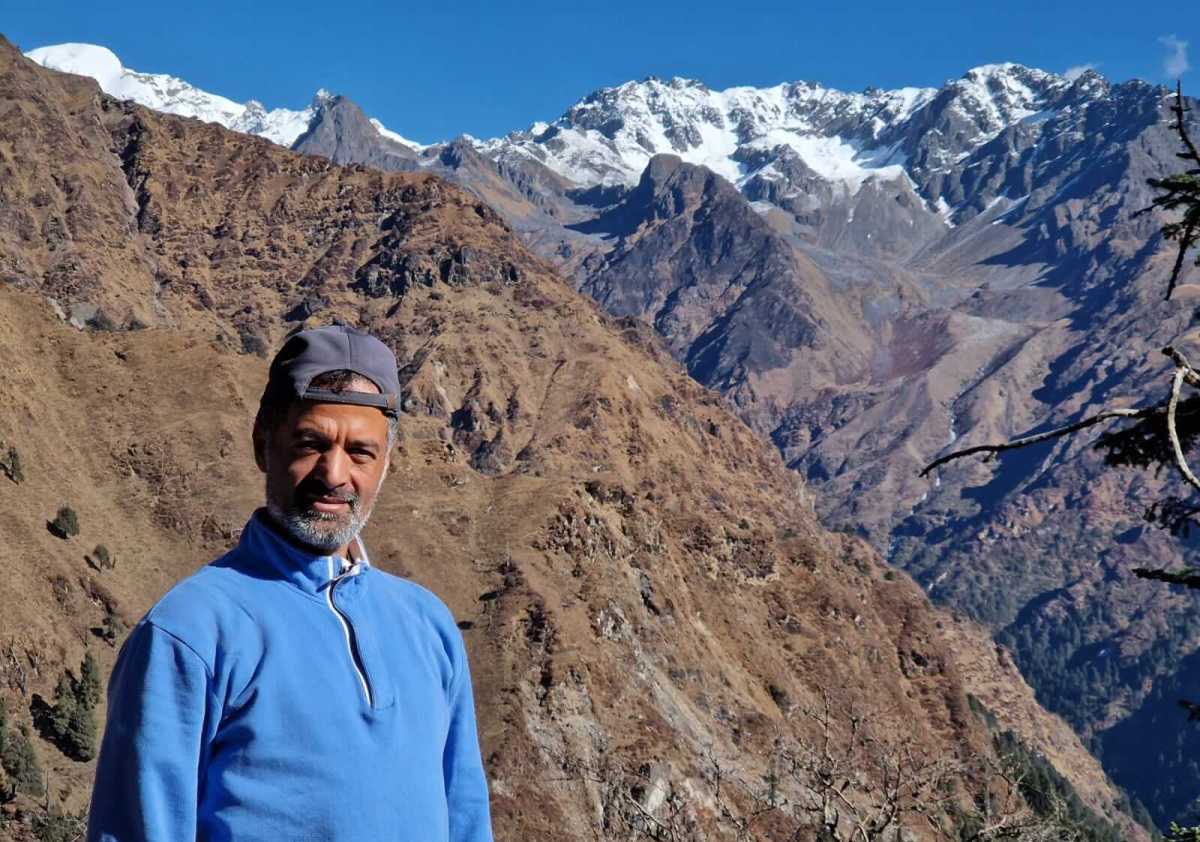

Over the past 15 years, Nepal, the Himalayan nation of just over 30 million people wedged between India and Tibet, has gained international recognition as a leader on LGBTQI acceptance, even though its advances have come haltingly. Probably nobody understands that story better than Sunil Babu Pant, who in 2001 founded the Blue Diamond Society, Nepal’s first LGBTQI advocacy group. Six years later, Pant won a spectacular victory in that nation’s highest court with a ruling that LGBTQI Nepalis deserve equal rights and freedom from discrimination under the law, including the right to marry. Based on the high profile he earned during his court challenge, Pant, in 2008, became the first out LGBTQI individual elected to a national parliament in Asia. Yet, despite the four years he spent in the Constituent Assembly and Nepal’s adoption of a new constitution in 2015, many of the dictates of Pant’s 2007 Supreme Court victory remain unrealized.

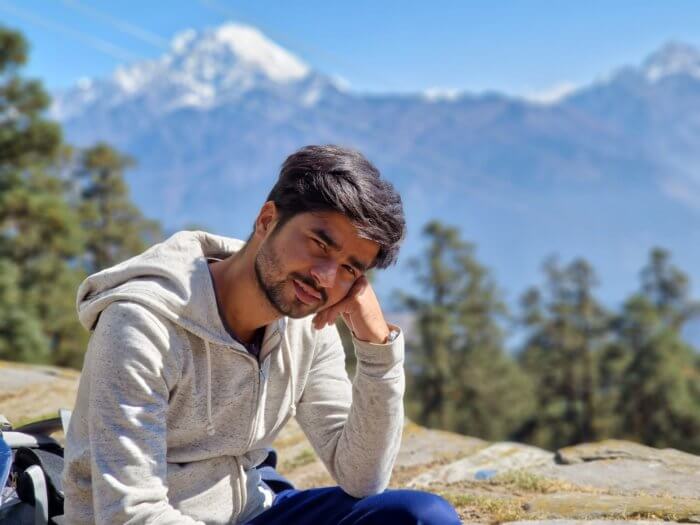

Pant, now embarking on a career as a filmmaker, has focused his first feature, produced with co-director Pradhumna Mishra, on a Nepali tradition he said traps many — gay men, lesbians, and others — in unhappy lives: forced marriage, the practice under which most young people are expected to enter into unions arranged by their parents. In “Blue Flower {Striving for the Impossibility},” Tilak — played by actor Sagar Ghimire, who compellingly conveys his character’s stoic desperation — is a young gay man from a rural family engaged in subsistence farming. As the 39-minute short opens, Tilak is being rebuked by his parents because he has twice run away rather than follow through on the marriage they arranged. When his mother suggests a third escape might lead her to take her life in shame, Tilak at last agrees to the marriage.

The couple’s union is predictably an unhappy one, with Tilak choosing to sleep on the floor rather than share a bed with his bride. When the couple produce no child, they are subjected to harping from Tilak’s family and rumors among their neighbors. Tilak’s manhood is called into question, but the deeper shame settles on his wife, who, the film makes clear, is judged to bear the greater responsibility for ensuring that a male heir is born. In a country where divorce is largely out of the question, both Tilak and his wife seem sentenced to lives shrouded in disgrace.

When Tilak gets the opportunity to leave his village for the city, he is able to escape the everyday pain of his life — and even to find love. However, the “middle path” he wins — which also allows his wife to bear a child to satisfy his family and community — is at best a compromise, and viewers are left uncertain as to how much pain and social pressure Tilak and his wife continue to endure.

Pant met the man on which Tilak is based in his early years organizing the Blue Diamond Society. Forced marriage, Pant explained in an interview with Gay City News, is the rule in Nepal — but something that is rarely discussed. Pant himself was raised in a rural village similar to Tilak’s — and his film beautifully captures the feel and rhythms of that way of life. Higher education allowed him to escape the strictures of tradition — unlike Tilak, who enjoyed no formal schooling — but Pant said even after two decades as Nepal’s most visible gay man, when he returns to his home village he still faces questions about when he will marry a woman.

Marriage customs in Nepal’s cities are no different than in rural areas, Pant explained, and are consistent across the predominant Hindu majority as well as Buddhist, Christian, and Muslim minorities. What distinguishes experiences on the farm from those in the city is the anonymity that allows young people to disappear more easily in populated places like Kathmandu, Nepal’s capital.

Forced marriage, of course, is a coercive institution, but “Blue Flower” does not vilify Talik’s family. The shame his mother feels after his two escape attempts is real; she seems as burdened by tradition as he. Yet, Pant’s description of the film on Facebook makes clear the tradition does not always play out in benign fashion.

“Many cannot say no to forced heterosexual marriage as they would be denied of ancestral property, often kicked out of home, and even murdered in many occasions,” he wrote.

Forced marriage is one of the anomalies of LGBTQI people’s status in Nepal, where the number of advocacy groups has now grown to roughly 40. According to Pant, Nepali culture is a generally tolerant one and since, unlike neighboring India, the nation did not face colonial occupation, it never had a Western-style sodomy ban in law. (A 1960s statute outlawing “unnatural sex” was judged by the government in 2004 not to apply to same-sex conduct.) Still, the cultural influence wielded by India, the country’s behemoth neighbor, reinforces patriarchal norms that discourage embrace of gay and lesbian people as well as gender identity and expression outside the male-female binary. Nepali patriarchal customs, Pant explained, have existed for several thousand years, after replacing earlier, indigenous matriarchal norms that celebrated same-sex relations and gender fluidity.

Even in the wake of Nepal adopting its 2015 constitution, the reality on the ground for LGBTQI people falls fell well short of the promise of Pant’s 2007 court victory. The nation now recognizes in law a “third gender,” though gaining such legal status is cumbersome for transgender people and they can only transition officially to “other,” not from male to female or female to male. Despite the constitution’s promises, nondiscrimination protections are not provided in practice, and the government’s policy of “inclusion” — guaranteeing minority group participation in Nepal’s civil society — has not benefited LGBTQI people. Nor has marriage equality yet been won, a fact that surely buttresses forced marriage traditions. While gay men and lesbians, Pant said, are generally coerced into heterosexual marriage, trans people are often rejected and forced out of their family homes.

Asked about his decision to leave his work as an elected official, Pant said it was due in large measure to his partner suffering a serious illness that led to his death five years ago. After that loss, Pant felt a calling to life as a monk, and spent several years in a Buddhist monastery in Sri Lanka. Over time, however, he felt chafed by the same patriarchal attitudes there that he had so long fought in Nepal.

In his work as a filmmaker, in which he splits time between Kathmandu and London, Pant has made an impressive start with “Blue Flower.” In cooperation with the US Embassy in Kathmandu, he plans to premiere the film in the capital later this month. From there, he hopes to bring “Blue Flower” to film festivals around the world where debate over forced marriage can find a receptive audience, such as those in which UNESCO or the UN Development Programme participates. These United Nations organizations that take on so many social issues globally, Pant explained, have yet to speak out about traditions of forced marriage.

Watch the “Blue Flower” trailer below: