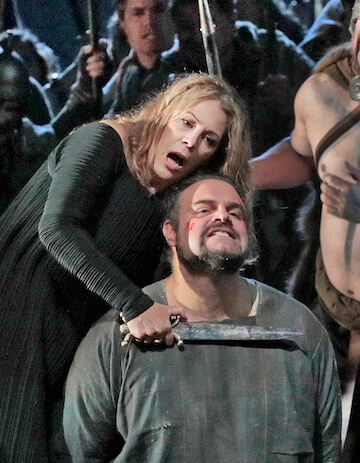

Jonas Kaufmann in the title role of Wagner’s “Parsifal” at the Met. | KEN HOWARD/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

Wagner’s “Parsifal” is not a conventional opera in dramatic structure, content, or conception and should not be staged like one. The Metropolitan Opera’s previous production — the least successful of the Otto Schenk/ Günther Schneider-Siemssen “romantic, realistic” Met Wagner productions — turned the opera into Disneyfied kitsch. I remember vividly the Astroturf valley in Act III, with fake daisies wobbling on wire stems.

The more “Parsifal” is liberated from a specific, literal, and overly narrow interpretation the more the viewer can ignore Wagner’s distorted concept of Christian theology and let the music weave its spell. A faction of the Met audience booed director François Girard at the premiere (February 15), ostensibly because they were not seeing long tunics and Romanesque arches onstage.

Wagner’s text does not specifically name Christ — only referring to “him” — and the text is allusive and ambiguous. Girard strips away literal religious iconography, keeping only the Grail and spear, while staying faithful to Wagner’s stage directions. In Act I, the forest near Monsalvat is a post-apocalyptic wasteland — striated dried earth with a narrow stream bisecting it. The Grail knights are a fundamentalist sect — all barefoot and dressed in white Oxford shirts and dark gray pants. They sit in a closed circle stage right while the black-clad female community is segregated stage left — never allowed into the sacred circle.

François Girard Met production triumphs, liberating “Parsifal” from Wagner pitfalls

Nature blasted by global warming serves as a visual metaphor for the spiritual desolation of the Order of the Grail caused by the physical and psychological wound inflicted on their leader, Amfortas. A scrim shows projected images of a cloudy sky, but when we enter the Grail Hall these are replaced by abstract images of earth and heaven. (Girard does overuse the projections — the Good Friday Spell in Act III resembled a planetarium show.) At the end of Act I, the earth itself takes on a rosy glow, looking like human skin magnified, while the stream turns into a gash of blood — the landscape transformed into Amfortas’ wound itself. Parsifal is drawn into its bleeding opening.

In the second act we are inside the wound itself — high crevice walls on either side with a pool of blood covering the entire stage floor. Kundry’s attempted seduction of Parsifal in the guise of a maternal figure — Wagner anticipates Freud’s Oedipus complex by 20 years — is underscored by the visual similarity of this space to the interior of a female vagina. Our hero has retreated into the womb, where he is spiritually reborn.

Act III shows the first act landscape in an advanced state of desolation and disorder — graves have been dug in the earth and light snow dusts the ground. Parsifal blesses Kundry, who officiates in the Grail ceremony and the male and female community are united in the final tableau. The lighting remains shadowy and oppressive throughout. The interior landscape of the mind and soul coexists on the same plane with the exterior physical world, which takes one right into the heart of Wagner’s symbolic drama.

The cast — especially the men, who were nearly ideal — was uniformly strong. Gurnemanz has the longest role in the opera and usually is an orotund, pontificating bore. René Pape played him as a vigorous middle-aged man who acts as the outspoken vocal conscience of the Grail Order. His long narratives were delivered conversationally with lieder-like intimacy — these were the stories of people he knew and a way of life he saw disappearing before him.

Peter Mattei’s Amfortas was acted with visceral physical intensity — his towering 6’4” frame barely able to support itself. His singing, on the other hand, had a gently lyrical, otherworldly beauty. Jonas Kaufmann was visually the ideal “pure fool” — an open-faced blank slate with a youthful tone. In the intense second act confrontation with Kundry, he surprised the listener with a huge, ringing baritonal resonance in “Amfortas! Die Wunde!”

Evgeny Nikitin’s Klingsor was too soft-grained, needing more biting German diction and harsher tonal attack. Debutant Rúni Brattaberg thrilled with true basso profondo tones as Titurel — his voice emanating from high up in the Met ceiling. Ryan Speedo Green arrested attention in his few lines as the Second Knight.

As Kundry, a role sung by both sopranos and mezzos, Katarina Dalayman found a comfortable fit for her low-seated soprano. A few upper register attacks were blunt and edgy and her acting lacked the detailed intensity of a Waltraud Meier or Gwyneth Jones, but Dalayman is an estimable artist.

Conductor Daniele Gatti favored a broadly phrased reading of the score with considerable variation of tempo throughout. But the rhythmic tension was well-sustained, with a sense of a rising forward motion. Gatti favored transparent shimmering textures over ponderous Teutonic weight. This “Parsifal” provided a rare occasion when all the elements fused into an overwhelming whole — a true gesamtkunstwerk.