Christine Goerke in the Mostly Mozart Festival’s “The Illuminated Heart” program. | RICHARD TERMINE

This year’s Mostly Mozart Festival kicked off on July 25 with an all-star gala concert of Mozart’s operatic hit parade billed as “The Illuminated Heart.” The stunning video projections, costumes, illuminations, and visual effects were designed by Netia Jones who also directed the show. A mix of familiar Mozart specialists and new voices performed beloved Mozart arias, duets, trios, and ensembles accompanied by the Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra led by musical director Louis Langrée.

Musically, the evening wasn’t very adventurous — the selections centered on the Da Ponte trilogy, the serious operas “Idomeneo” and “La Clemenza di Tito,” and one aria from “Die Zauberflöte.” “The Abduction from the Seraglio” went unheard but we did get the ravishing “Ruhe sanft, mein holdes leben” from Mozart’s obscure “Zaide.”

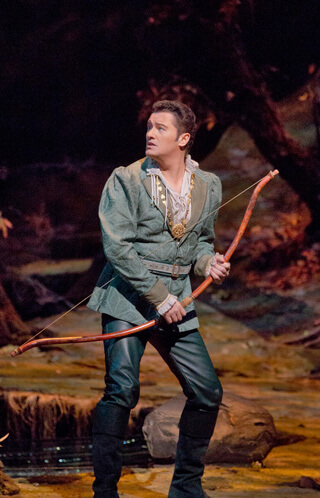

The evening kicked off with a fleet, weightless rendition of the overture to “Le Nozze di Figaro” led by Langrée. Peter Mattei repeated his familiar Conte Almaviva with a darker more menacing sound but also unveiled a potentially fascinating Don Alfonso in the trio and Act I finale from “Così fan tutte.” Christopher Maltman was pleasant but forgettable in Papageno’s and Don Giovanni’s arias. Singing Don Ottavio’s “Dalla sua pace,” Matthew Polenzani was musical but vocally inhibited. Polenzani then gave a promising preview of his Idomeneo at the Met this coming season in the lovely quartet “Andrò ramingo e solo” (supported by Nadine Sierra, debutante Marianne Crebassa, and Christine Goerke). Goerke heard more often recently as Strauss’ Elektra than as Mozart’s Elettra in “Idomeneo,” emerged late in the evening with a fire-breathing “D’Oreste, d’Aiace” that brought down the house. She proved surprisingly supple vocally — had she been given more to sing (maybe Donna Anna?), she might have stolen the show.

Strong evenings helmed by Louis Langrée and René Jacobs

The title of top diva of the night was a close contest between mezzo-soprano revelation Marianne Crebassa, rising ingénue Sierra, and the locally underexposed Ana Maria Martínez. Martínez’s dark but cool soprano sailed through the intricate difficulties of Fiordiligi, the Countess Almaviva, and Donna Elvira, easily surpassing the recent efforts of Susanna Phillips, Amanda Majeski, Miah Persson, and Emma Bell in these roles at the Metropolitan Opera. Sierra went from soubrette to ingénue as Susanna, Ilia, Servilia, and Zaide, bringing a mix of silvery spin and creamy sweetness to each role. Her quick vibrato added emotional urgency and vulnerability. For me, the vocal pinnacle of the evening was French mezzo Crebassa singing Sesto’s “Parto, parto” from “La Clemenza di Tito,” with clarinet obbligato played by Jon Manasse. Crebassa’s liquid supple tone mixes equal parts mahogany richness and gleaming point with a virtuoso command of scales and trills.

Langrée and the Mostly Mozart Orchestra played with increasingly sensitive lyricism expertly supporting the soloists. Mostly Mozart should repeat this staged concert gala concept in the future but highlight instead the less familiar Mozart operatic, oratorio, and concert aria repertory.

On August 15, Langrée led the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra in a staged concert reading of “Così fan tutte” with the same sextet of soloists from the Aix-en-Provence Festival production he conducted earlier this summer. However, the controversial Christophe Honoré stage production from Aix was jettisoned for a blandly superficial updated concert staging by Annette Jolles –– business suits for the men, floral cocktail dresses for the women tripping through a shallow farce that lacked emotional depth and ambiguity.

Langrée’s musical interpretation of this complex sex comedy was equally superficial and bland –– the Freiburg forces sped through the overture with little or no inflection and coarsely edgy string tone. The strings, woodwinds, and horns all blared away on the same sonic plane. The relentlessly loud orchestral balances consistently overpowered the soloists as if Langrée forgot the orchestra was playing onstage in the intimate Alice Tully Hall. By Act II when the story gets complicated, the orchestra settled down and Langrée seemed more attentive to the singers and musical nuances.

The cast was a mixed lot of seasoned veterans and unfamiliar young singers. The cynical pair of manipulators Don Alfonso and Despina, as sung by the veterans Rod Gilfry and baroque diva Sandrine Piau, dominated the proceedings. Gilfry, dressed up in ascot and bespoke suit, projected cool malevolence under a suave, affable country gentleman façade. His baritone never has sounded more secure or richly resonant. Despina is a tricky role that either pushes the singer into vulgar exaggeration or soubrette cutesiness. Piau expertly maneuvered between these two clichés, balancing the cynicism of experience with the joie de vivre of a mature woman with a youthful appetite for sensual pleasures. Piau’s brightly glinting soprano danced over the notes except for some blatant interpolated cadenzas that sounded forced.

Of the younger lovers, Kate Lindsey stood out with a Dorabella who transformed from a romantic girl to a liberated woman relishing her newfound sexual power. Lindsey’s singing was as bold and sensual as her acting. Three young singers made Mostly Mozart debuts –– Dutch soprano Lenneke Ruiten as Fiordiligi, tenor Joel Prieto as Ferrando, and bass-baritone Nahuel Di Pierro as Guglielmo. Luiten’s neat rather undistinctive soprano accurately hit all the notes in “Come Scoglio” except for the trills. However, her slender tone lacked color, depth, and authority failing to move the listener in “Per pieta.” Prieto’s long locks and smoldering looks were more plausibly romantic than his rather shallow lyric tenor voice. Di Pierro boasted a fruity bass-baritone and lively temperament as Guglielmo, despite some loose phrasing. This “Così” achieved real artistic distinction only in a few individual performances rather than the overall musical or dramatic conception.

Cult maestro René Jacobs took over the baton to lead a sold-out concert performance of “Idomeneo” on August 18 at Tully Hall. The Freiburg Baroque Orchestra sounded transformed from their unfocused work in the unevenly cast “Così fan tutte” concert earlier that week. Despite his reputation for unorthodox and provocative musicological theories and period practices, Jacobs when he gets onto the podium is a supreme musical dramatist striving for bold color and expression. All evening Jacobs discovered in Mozart’s youthful opera seria infinite varieties of color and emphasis as changeable and overpowering as the mighty ocean itself that looms in the background of the opera.

Jacob’s interpretation of “Idomeneo” was more theatrical than Langrée’s glib “Così” days earlier, despite the “Così” cast and conductor having participated in staged performances in June. Tenor Jeremy Ovenden in the title role of Idomeneo proved a sensitive, thoughtful interpreter despite a voice on the small and dry side for the role. Ovenden’s rendition of the full-length virtuoso “Fuor del mar” was more a triumph of musical intelligence and intention than vocal heroics. Belgian soprano Sophie Karthäuser as the captive Trojan princess Ilia revealed a voice of real substance with gleaming tone, long breath, and firm resonance, suggesting a young woman of character and authority, not a pathetic maiden. French mezzo Gaëlle Arquez debuted as a youthfully moving Idamante displaying a slender bright sopranoish sound with a quick vibrato.

Alex Penda is well remembered by New York audiences for her demented diva performance in the title role of Rossini’s “Ermione” back when City Opera was City Opera and she was the multi-syllabic Alexandrina Pendatchanska. Since dropping the syllables, Penda has taken on roles like Fidelio and Salomé. Her voice is now darker and less supple without gaining in size or power. However, as the angry princess Elettra, Penda’s fiery temperament, vivid textual delivery, and authoritative stage presence were evident from her first entrance. Her tone was covered in her entrance aria, and in the lyrical “Idol mio” la Penda had noticeable trouble floating the vocal line. Demented divas cannot help but chew the scenery in “D’Oreste, d’Aiace,” and there Penda found her footing, tearing a passion to tatters and earning a long ovation late in the evening.

Fine supporting work from tenor Julien Behr as Arsace and Nicolas Rivenq as the High Priest of Neptune added to the success of the evening. The underpopulated Arnold Schoenberg Choir lacked ensemble power in Mozart’s powerful “O Voto Tremendo” chorus.

One hopes René Jacobs will return here often and soon.

Langrée revealed himself a better conductor of religious and oratorio music than opera on August 19, leading a double bill of Mozart’s “Mass in C Minor” and “Requiem.” Both works were left unfinished by the composer –– we heard Langrée’s completion of the “Mass” and a completion of the “Requiem” by Süssmayr, Eybler, and Langrée. The “Mass in C” is a well-constructed but rather impersonal work which lacks religious fervor –– it seems almost an academic musical exercise. The “Requiem” was composed during Mozart’s final illness and has premonitions of mortality presenting the composer in full maturity.

Langrée brought musical clarity to both works, operating on a cooler, more objective level and avoiding the Romantic pathos earlier conductors have imposed on the “Requiem.” Soprano Joélle Harvey brought an ethereal radiance to the soprano parts in each work, melting the heart in “Et incarnatus est” from the “Mass.” Mezzo Cecelia Hall impressed with her precise scales in solos and duets. Alek Shrader in the tenor parts sang accurately but stiffly. The resonant firm bass of Christian Van Horn impressed in the “Requiem.”

The Concert Chorale of New York under the direction of James Bagwell dominated the proceedings, bringing sweeping emotional power to Mozart’s choruses.