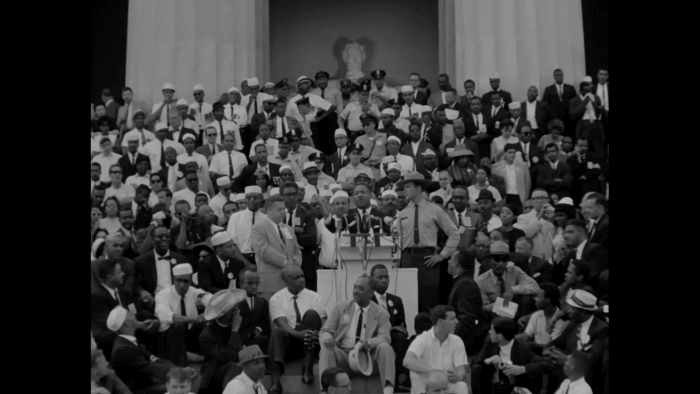

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s life tells a much larger story about American attitudes towards race, sex, and celebrity, even if most of this was hidden at the time. That’s one of the major takeaways from Sam Pollard’s documentary “MLK/FBI.”

Unfortunately, King’s pacifism and relative moderation compared to Malcolm X and the Black Panthers made him easier to sanitize posthumously. He’s been reduced to the “I have a dream” speech and seen as a symbol of respectability politics by people who’ve never known that he identified as a democratic socialist and spent his last years advocating economic justice and fighting the Vietnam War. In 2027, the FBI will release its original surveillance tapes of King, which it used in the ’60s to attempt to blackmail him and even try to convince him to kill himself over his adultery. “MLK/FBI” ends by wondering what might happen to his legacy then.

Pollard built his film’s visuals almost entirely around archival footage. His strategy may have been influenced by Goran Olsson’s “The Black Power Mixtape, 1967-1975,” which was based upon unaired Swedish interviews with Black activists of that period. Pollard talked to authors Beverly Gage, David J. Garrow (whose King biography inspired by the film), and Donna Murch; politician Andrew Young; King’s former speechwriter and advisor Clarence Jones; and former FBI director James Comey. But “MLK/FBI” never shows their faces until its final 10 minutes. Their voices play over news clips from the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Although their names appear onscreen, the present never dominates the past. Instead, the two time periods interact in provocative ways.

Pollard briefly mentions King’s gay friend and fellow activist Bayard Rustin. He never explicitly brings up J. Edgar Hoover’s closeted sexuality, but the film alludes to it constantly and coyly, in its choice of images and words from Gage and Murch. Like Roy Cohn, Hoover looks like a real-life version of the repressed gay fascist in Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Conformist.”

But when one commentator describes the image of the ideal G-man, as promoted by Hollywood and enacted in real life — six-foot tall conservative white men, with an athletic fraternity background — one wonders if this had any connection to Hoover’s libido. This speculation seems relevant because his beef with King was remarkably personal, even sexual. “MLK/FBI” points out how the FBI’s obsession with King’s adultery played into America’s long-standing fear of Black men as hyper-sexual beasts. Hoover and FBI intelligence director William Sullivan claimed to be outraged that a man with a “deviant” sex life of adultery was respected as a moral leader. But the film suggests that he also envied that sex life.

“MLK/FBI” winds up dominated by its soundtrack. Its sparing reenactments can’t help looking cheesy compared to reality. It frequently appears to be editing together B-roll as accompaniment to a far more compelling voice-over. The recurring image of a spinning reel-to-reel tape recorder loses impact upon repetition. The use of TV and movies glorifying the FBI, which it blames for giving Americans an unrealistically positive image of the agency, has a much greater impact. (This practice hasn’t ended; TV is still full of shows suggesting the FBI does nothing but protect women from serial killers.) A movie title like “I Was a Communist for the FBI” is laugh-out-loud funny now, but it laid the path for the McCarthyist smears by which King was dogged. “MLK/FBI” suggests that the anti-communism espoused by pop culture copaganda was grounded in a fear of Black people as recruits challenging America’s supposedly benign history.

Towards the end, “MLK/FBI” brings up a 1968 FBI report which suggests that King observed a rape by a Baltimore minister in a hotel room and stood by laughing. It offers plenty of good reason to doubt its truth; beyond the fact that the FBI was desperate to destroy his reputation, this was handwritten in an otherwise typed memo and supposedly came from eavesdropping rather than direct sight. But the film nevertheless treats this like a bombshell, opening up doors and possibly reinforcing stereotypes that it doesn’t entirely seem comfortable dealing with. At the end, its subjects disagree about whether the surveillance tapes should be released, but most think King’s status is secure no matter what they contain. The fact that this question would even have to be asked at the end of the presidency of a white man who publicly screwed his way through Studio 54 and porn sets, allegedly with little respect for women’s consent, shows America’s double standards.

MLK/FBI | Directed by Sam Pollard | IFC Films | Starts streaming through Film at Lincoln Center Jan. 15