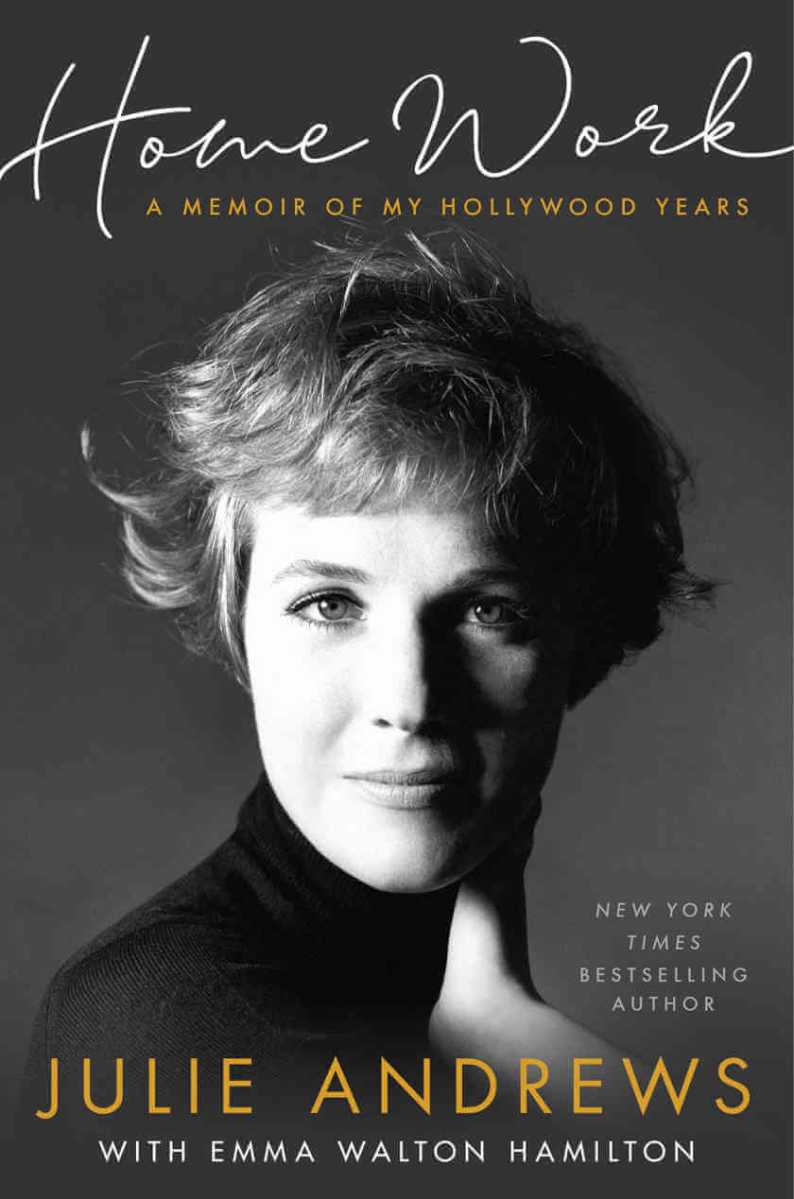

Eleven years after “Home: A Memoir of My Early Years,” Julie Andrews now has a second autobiographical volume, “Home Work: A Memoir of My Hollywood Years,” which covers her busy movie-making period, from her Oscar-winning film debut in 1964’s “Mary Poppins” to 1995. To promote it, she made a special appearance before an audience of worshipful fans last month at the 92nd Street Y, accompanied by her daughter and co-writer Emma Walton Hamilton (whose father Tony Walton, Andrews’ first husband, is the genius set and costume designer behind “Mary Poppins,” as well as a host of memorable Broadway productions like “Guys and Dolls”).

At age 84, Dame Julie (knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 2000), who entered to a tumultuous ovation in an all-purpose, simple, long black jersey dress and very sensible heels, is, happily, still very spry in mind and body, and the evening was a wonderful and warm celebration of her legendary cinema status, though she herself is so down to earth and unlike any diva that she would probably blanch at that description.

Still, Andrews is well aware of the position she holds in both the industry and the hearts and minds of generations of kids who grew up having her as a touchstone. Plus, she is one damn good storyteller, with an inexhaustible fount of anecdotes — though I know her career pretty well, she kept coming up with fresh surprises.

She was particularly candid about the severe depression suffered by her second husband, the late director Blake Edwards. Though she has suffered from it, too, therapy — which she has heartily recommended — helped pull her through, but she could never quite understand the reasons for Edwards’ malaise, with such a successful career and happy family life (including two daughters orphaned by the Vietnam War, Amy and Joanna, whom the couple adopted).

A clip from “That’s Life!” (1986) was shown, a film that was a kind of therapy for Edwards, who cast family and friends in roles he had them write for themselves. Andrews confided that the lines she spoke when confronting the depression of her movie husband (Jack Lemmon) were indeed her own reflections about her marriage to Edwards.

One quibble was the choice of film clips screened. Besides the obvious moments from “Mary Poppins” and “The Sound of Music,” the event’s moderator, Annette Insdorf, said the not one, but two clips from Paddy Chayefsky’s “The Americanization of Emily” were chosen by her husband, as it is his favorite film. (What film critic curates an evening in this way?) One would think something from Andrews’ epic, image-changing “Hawaii” (in which she had an agonizing, protracted childbirth scene) might have been chosen or, better yet, a clip from the much-maligned extravaganza “Star!,” the Gertrude Lawrence biopic that was a colossal flop but holds up today. Its script may have been vapid but the succession of opulent musical numbers from all the great Broadway composers — fabulously arranged by Lennie Hayton, choreographed by Michael Kidd, and costumed by Donald Brooks — allowed Andrews to display dazzling dance skills as well as that voice at its most youthfully crystalline and pure. Her “Someone to Watch Over Me” remains definitive in my book.

An unexpectedly special aspect of the evening was the use of a video monitors facing the stage during the clips, so we could watch Andrews watching them, instead of requiring her to turn her head behind her. Her expressive face, especially during the “Victor/ Victoria” moments, was truly a sight to behold. Intermittently, the star’s own true nature — much more earthy and bawdy than her screen image — broke through, to the delight of all. In describing her writing process with her daughter, Andrews said that when they would reach an impasse over whether or not to include anything particularly personal, “A bathroom break comes in handy. In fact, some of my best ideas have come to me there.”

As I exited the 92nd Street Y, I noticed a sizable crowd of Julie-ites, waiting for her at the stage door, most of them clutching items to be autographed. The excitement was palpable, and it was reassuring to see that in this media-bludgeoned age the power of a true and worthy star still exists. I lingered a bit, myself. Upper East Siders, strolling home from dinner, stopped as all New Yorkers do to ask what was the fuss? I reveled in seeing their blasé masks instantly turn into wonder and delight as they, too, chose to hang back a bit. It was one of those Our Town moments that continue to make living here so special.

A true inheritor of Andrews’ mantle of Broadway golden girl, Melissa Errico, seems to have solved the problem of what a diva is to do when they age out of musical ingénue roles but are unwilling yet to don those hideous spandex outfits in “Mamma Mia.” Errico’s solution: align yourself with a truly great, eternally relevant composer as she has done with Michel Legrand, continuing as his muse, even after his death (this past January), as well as full-time champion of his entire oeuvre.

She met Legrand in 2002, as the star of his only Broadway musical, “Amour.” In 2011, the two collaborated on the CD “The Legrand Affair,” luxuriously backed by the 100-piece Brussels Philharmonic, and since then she has been singing his songs steadily.

Last spring, Errico hosted Alliance Francaise’s festival of the films he scored, including 1968’s “The Thomas Crown Affair,” with that famous erotic chess game scene with Faye Dunaway and Steve McQueen. The piquant music for this sequence had lyrics written for it by Legrand’s frequent, brilliant collaborators, Marilyn and Alan Bergman, and became the song, “His Eyes, Her Eyes,” which Errico has gloriously made her very own.

Chosen by The New York Times to write an appraisal of Legrand at the time of his death and the only American artist invited to perform at his memorial in Paris, Errico just released “Legrand Affair (Deluxe Edition),” an updated and extended version of their 2011 creation. She was going through her Legrand memorabilia after his death when she came across a cache of homemade tapes of her singing with him at the piano, sketches for what was to become their album. Hearing these tracks, she said, “reminded me of how much I also love hearing more intimate versions of his music. In Michel’s music, genre doesn’t exist — he was unencumbered by boundaries. His plurality of disciplines became his freedom and made one seamless web of music. I’m happy beyond words to be able to put his energy back into the world.”

And, boy did she ever, at Feinstein’s/ 54 Below on November 8! Backed by a brilliant band led by the greatest living non-classical accompanist today, Tedd Firth, who was simply on fire, Errico, bursting with passion for her mentor, delivered a rich feast of reminiscences and anecdotes in her distinct “talking cabaret” style, as well as sumptuous song, in which she totally lost herself, sometimes literally becoming the music. Her voice is crystalline and clarion, as silvery and refreshing as a mountain stream, and she did a segue from “His Eyes, Her Eyes” to the lulling, sensual “The Summer Knows” that took my breath away.

Legrand and the Bergmans’ masterpiece, I believe, was the song “What Are You Doing the Rest of Your Life?,” and Errico noted that its composition was rare in that its lyrics came first and then were then set to music. When Legrand looked at the song’s title, he went to the piano and played the first nine notes for it, instantaneous and perfect, such was his musical fecundity. To me, this revives long-disputed question — are songs better when the words come first, as was the case with Rodgers and Hammerstein?

The evening of November 7 saw me at the premiere of the very moving and very fun documentary “I’m Gonna Make You Love Me,” as part of DOC NYC’s festival. Karen Bernstein and Nevie Owens’ film details the utterly wild and surprising life and times of Brian Belovitch, a gay boy from Providence who transformed himself into downtown sexpot club diva Tish (aka Natalia) Gervaise, had a short-lived marriage to a US soldier while he was stationed in Germany, and, eventually bored with that, moved back to New York and decided to begin her transition back to being a man. It is, above all, a story of survival at a time when trans folk were not nearly as accepted as they are now. Through the process, Belovitch made the all-important life discovery that you sure better love yourself, because sometimes even family fails to come through in that department.

At the intimate celebratory dinner for the film at Le Zie, hosted by Belovitch and his class act of a husband, Jim Russell, I was thrilled to meet Rose McGowan, looking exquisitely the spitting image of Jean Seberg in “Breathless” with short-cropped platinum hair. She was just lovely — warm, down to earth, and fun, dishing the dirt about funny encounters with Jack Nicholson and Peter Weller, as well as about running away from her Oregon home at 14 to come to New York. After her 2018 memoir “Brave,” she’s planning a second book, which will cover her earlier wild years.

A companion piece to the Belovitch film in the fest was “Pier Kids,” Elegance Bratton’s terrifically real and gritty portrait of the homeless queer and trans youth who hang out at the place most of them consider a kind of home: the Christopher Street Pier in Greenwich Village. Bratton was kicked out of the house at 16 for being gay, and was homeless for a decade before joining the Marines in Hawaii where he learned filmmaking, later getting degrees from Columbia and NYU.

“Pier Kids,” doesn’t have the flamboyant, strutting ballroom footage found in Jennie Livingston’s seminal “Paris is Burning” (1990), but even with the pier’s beautiful facelift compared to its decrepit and dangerous state of 30 years ago, not much has really changed for the kids who are drawn there. This new generation still has to hustle hard, often doing sex work to put food in their bellies and living and surviving day to day in the face of deep prejudice, police oppression, and sometimes lethal violence. A young male interviewed in the film talked seriously about whether getting infected with HIV — and thereby collecting benefits — might be the best option for finding stability in his life. These are kids we continue to fail.