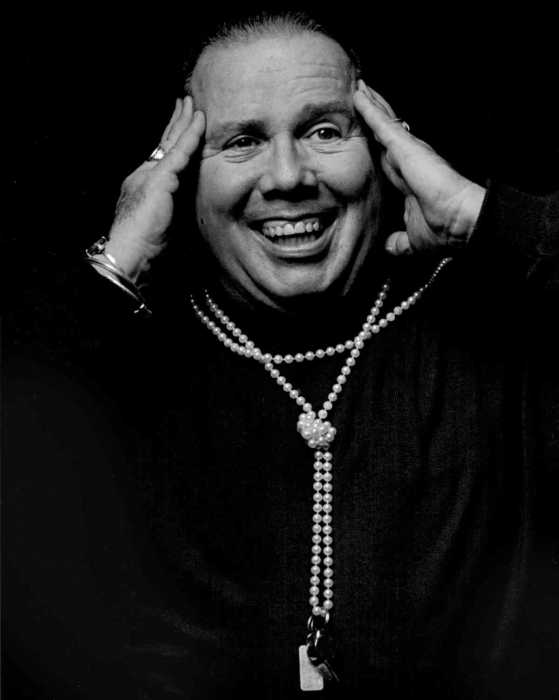

Mayor Bill de Blasio at a May 22 press conference. | GAY CITY NEWS

When Mayor Bill de Blasio spoke at a World AIDS Day event this past December 1, he boldly endorsed a plan to reduce new HIV infections in New York from the current roughly 3,000 annually to 750 a year by 2020.

“Hope will never be silent, and that’s what you’ve all proven,” de Blasio said. “And your voices have reached Albany and I commend Governor Cuomo for last June setting the goal of ending the AIDS epidemic by 2020… And I want to thank so many of you who are part of that effort because this is the kind of goal that galvanizes us. And we will be working with community leaders. We will be working with health care professionals, everyone who has something to offer in that fight to achieve that goal.”

In large measure, that goal relies on identifying HIV-positive people and treating them with anti-HIV drugs so they are no longer infectious. And it uses pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), anti-HIV drugs given to HIV-negative people to keep them uninfected. Candidates for PrEP and treatment as prevention (TasP) — the latter appropriate for those with the HIV virus — will be found at the city health department’s nine sexually transmitted disease clinics, among other locations.

Advocates criticize lack of city planning to replace lost STD services, but hopeful solutions in the works

So when the city closed its Chelsea clinic on March 21 for a necessary two-year renovation with no apparent plan to replace the roughly 20,000 visits that clinic gets every year — the most among the nine clinics — community leaders were unhappy.

Asked at a May 22 press conference if the city ever had a plan to replace the services lost when the Chelsea clinic closed and if it will spend the money needed to maintain those services, de Blasio said, “I always try to be careful, I don’t have the details. I don’t want to speak beyond my knowledge. I think it’s fair to say our health commissioner, Mary Bassett, has been extremely careful and conscientious in making sure resources are available to the community.”

In some respects, the Chelsea clinic closing is emblematic of the early going in the Plan to End AIDS. The plan has political support, but not a lot of cash.

When Governor Andrew Cuomo endorsed the plan last year, he also announced that he had negotiated reduced prices for the anti-HIV drugs that are a central component of the effort. His budget for the state fiscal year that began on April 1, however, only included $10 million in new spending for the plan. Advocates were looking for over $100 million.

In the preliminary budget for the city fiscal year that begins on July 1, de Blasio cut the budgets for the health department and the Human Resources Administration, the two city agencies that will contribute the most resources to the plan. Those cuts were partially restored in the mayor’s executive budget, which was introduced on May 7. Responding to the preliminary budget, the City Council proposed $9.7 million in new spending for the plan. That cash was not in the executive budget.

The frustration with the Chelsea clinic closing is due to the city knowing that the renovation was pending for at least seven years and getting the required permits for it approved over the course of 2014.

Currently, the health department is sending prospective clinic visitors to its clinic on West 100th Street. It is paying for six non-profits to park testing vans outside the Chelsea clinic five days a week. The department is contemplating parking a trailer, which will replace the vans, outside the clinic for the duration of the renovation that will provide some of the services the clinic supplied and refer visitors to three Manhattan non-profit clinics.

In an email, Mark Harrington, executive director of the Treatment Action Group, wrote, “The community has provided detailed recommendations to [the health department], to elected officials representing Chelsea, and to [Deputy Mayor Lilliam Barrios-Paoli] and the Mayor regarding the urgent need to fully replace all activities suspended at [the clinic]. Somewhere in Chelsea, ideally close to the original site. To date, my understanding is that while the Deputy Mayor's office has been supportive of fully resourcing a solution to the problem, [the health department] has failed to propose an adequate interim solution.”

Harrington called the health department’s approach to the clinic closing “epic incompetence.” Jim Eigo, a member of ACT UP New York, wrote that the health department had “badly botched planning for the closure. (How badly? Words fail!).”

Following a meeting among advocates, elected officials, and senior health department staff on May 15, Eigo told Gay City News, “We’re going to miss a lot of people who are in acute infection and we’re going to miss a lot of people who are candidates for PrEP.”

Harrington, at that time, lamented the lack of adequate city planning on issues also including the persistently high rate of syphilis and hepatitis C in Chelsea, saying, “The other thing we found out is that the city doesn’t have a plan to address the syphilis epidemic. They have to have a clear syphilis response. They don’t.”

Eigo wrote that activists, the health department, and City Councilmember Corey Johnson, the out gay Health Committee chair who represents Chelsea, appear to be approaching a solution. They “secured the support of most of the relevant local politicians (city, state and fed) to support having an ‘enhanced’ trailer at the site that would be equipped to do a full range of STD and HIV testing, free & anonymous. The cost for a trailer that would have the capacity to test about six thousand people a year on site is modest.”

Throughout the recent controversy, Johnson has been more charitable than the advocates, pointing out that, since 2008, the health department had investigated 80 alternative sites to provide services during the Chelsea renovation, but none was suitable. Asked if the health department did not plan for the closing, he said, “That’s not my impression. I think the planning could have been better.”