Douglas Williams and members of the Mark Morris Dance Group in Mozart’s arrangement of Handel’s “Acis and Galatea.” | RICHARD TERMINE

Handel’s pastoral masterpiece “Acis and Galatea” started out in 1718 as an English masque based on a theme from Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” and evolved into a bilingual “serenata” (a semi-staged concert opera in costume) in 1732 and was expanded into a two-act “little opera” in 1739. It was incredibly popular during Handel’s lifetime and for decades after — buoyed by hit tunes like “Love in her eyes sits playing,” “Hush ye pretty warbling quire,” and the duet “Happy we!” Mozart reorchestrated Handel’s score in 1788 for a music-loving baron.

Mark Morris’ staging of “Acis and Galatea” as an opera-ballet for his company (in Mozart’s arrangement) premiered last April in Berkeley. His 1988 choreographic setting of Handel’s oratorio “L’Allegro, Il Penseroso ed il Moderato” is one of his greatest achievements, and his “Dido and Aeneas” (1989) is another brilliant fusion of modern dance and baroque opera. The Mostly Mozart Festival brought Morris’ “Acis and Galatea” to Lincoln Center for three eagerly anticipated performances earlier this month, and the new work joyously lived up to expectations.

A masque is a genre based more on dance and elaborate visual tableaux than straightforward dramatic action. John Gay’s libretto for “Acis” (with contributions by Alexander Pope and John Hughes) lacks conventional musico-dramatic structure. Act I consists of static vocal showpieces interspersed with choruses and dances celebrating the joys of love and nature. In Act II, the lustful giant Polyphemus shows up to add some needed dramatic conflict in the familiar operatic recipe of a romantic triangle and murder.

Reorchestration of Handel’s “Acis and Galatea” gets Lincoln Center opera-ballet staging

Pastoral pieces of the era extolled the joys of simple rural life in classical style, with subtle touches of wit and self-parody for the courtly sophisticate. Morris’ choreographic style is similarly characterized by a juxtaposition of classical symmetry and precise musical phrasing with loose physical abandon spiked by wicked comic touches and idiosyncratic flourishes. Dance provides the physical and theatrical movement Handel’s pastoral lacks.

Morris’ dance ensemble creates a kind of kinetic visual orchestra accompanying the soloists — sometimes they pantomime words or actions referenced in the text and at other times comment on the action. The dancers jump and twirl joyously to the music but also can be turned into the boulder with which the giant kills the shepherd Acis. In a disturbing counterpoint to the lustful Polyphemus’ solo “Ruddier than the cherry,” the dancers move around the giant in a circle while he gropes and fondles each one in passing. Dance is the element that fuses joyous music to an untheatrical libretto, creating a vibrant, entertaining, complete work of art.

Adrianne Lobel’s transparent scrims and flying drops depict forest glades in a naïve fauvist style. Isaac Mizrahi dressed the dancers in light flowing dappled green fabric — loose tunics for the women, billowing sarongs for the bare-chested men. Michael Chybowski’s lighting design underscores the shift from innocent joy to stark tragedy in Act II with the golden glow of springtime turning into stark gray twilight. One brutal spotlight transfixes Galatea in her grief like a deer in headlights.

Musically things were in safe hands with Handel specialist Nicholas McGegan leading the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra and Chorale (the chorus remained in the pit) in a fleet, spirited reading, with silken Mozartian strings contrasted with bracing Handelian woodwinds and horns. The singers, dressed in simple modern clothing in woodland hues, all had light youthful instruments. Disappointingly, Morris gave them minimal blocking — they merely stood and sang for the most part.

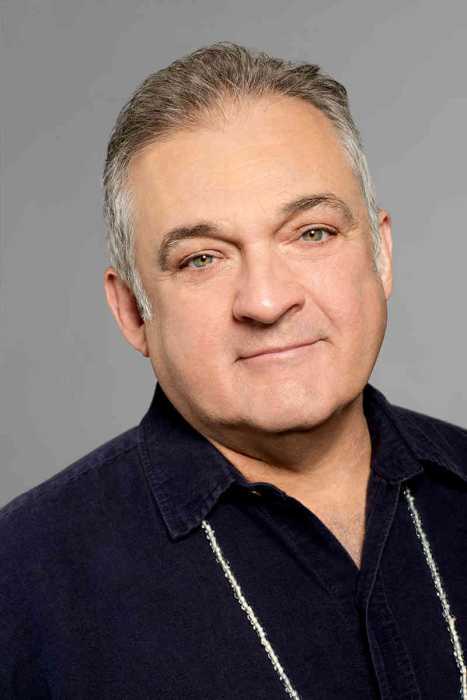

Only bass-baritone Douglas Williams as a lithe, lanky Polyphemus interacted with the dancers and performed detailed physical business. As Galatea, Yulia Van Doren’s crisp, slender soprano was well-balanced and youthful. Tenor Thomas Cooley as Acis displayed expert diction, clear tone, and incisive musicianship. Oddly, lyric tenor Isaiah Bell as the hero’s friend Damon had a more youthfully romantic tone quality and stage presence than Cooley.

The tall, handsome Williams has a rather light baritonal sound for a menacing giant but has strong stage instincts. He brought an appropriate mix of the sinister and buffoonish to his characterization. The final tableau of Acis transfigured into an immortal river was a vision of harmony and joy. The audience exited the theater into a clear, serene summer evening with an enhanced sensitivity to beauty — in art, nature, and living.