Should you find yourself in London next week, check out “Reunion 79:21 – Revisiting Black Queer London Clubland” at the Great Pulteney Street (GPS) Gallery in Soho.

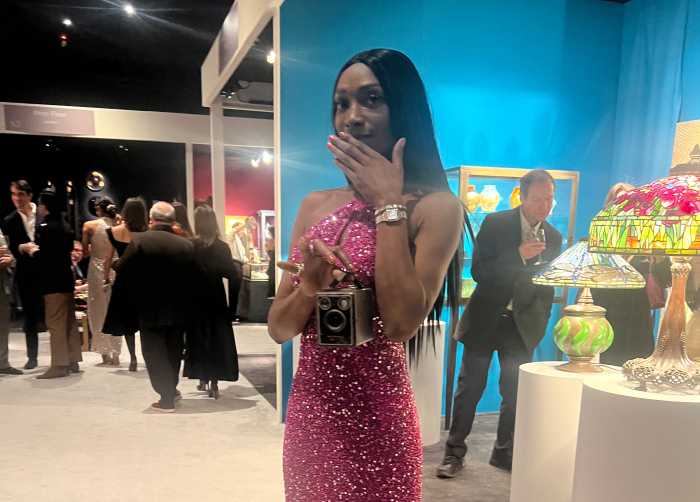

Running from Wednesday, Jan. 21 to Sunday, Jan. 25, this fashionably brief exhibition explores Black queer nightlife in the British capital between 1979 and 2021 through photography by veteran lensmen Dave Swindells and Jason Manning, film and memorabilia from public and private sources.

If a trip across the pond is not in the cards for you, despair not, this exhibition is intended to inaugurate an online forum where former club aficionados and attendees can share stories and images to build a virtual archive.

“Reunion 79:21” contextualizes the development of London Black queer nightlife amid a cyclone of impacts, including racial exclusion or invisibility, homophobia, the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and gentrification and soaring rents, which blurred the Black queer presence in the big picture of both LGBTQ and Black histories.

“My idea for the exhibition was to weave together the web of promoters, personalities, parties, places and people that brought about the unique cohesive magic that is clubland across two distinct generations,” says curator Shaun Wallace, 57, who produces events through his organization, Arc of Triumph UK.

GPS Gallery launched in 2024 in a building owned by the Soho Housing Association to provide affordable exhibition space in central London to modestly funded projects.

This show adds to a broader retrospective on Black queer cultures and community-building offered in two recent exhibitions, both of which showcased the pioneering rukus! archive, Europe’s largest public collection of Black LGBTQ+ materials, co-founded in 2000 by photographer Ajamu X (b. 1963) and filmmaker Topher Campbell: “Making a rukus!” at Somerset House, and “My rukus! Heart” at Tate Modern.

“Ajamu and Topher, and now ‘Reunion 79:21,’ are laying foundations for this and future generations,” says Wallace. “None were there for us.”

In the following Q&A, Wallace shares more of his exhibition’s objectives.

How did the idea for this exhibition come about?

SW: The exhibition came about from my lived experience as a Londoner going to clubs through these decades. Because clubbing culture encompasses so much – fashion, creativity, social interaction – and has become a significant income generator, I thought an exhibition of this kind would be of interest to people from different angles and from diverse communities.

My intention as curator of the exhibition was not to produce a chronology of Black queer clubs.

There have been quite a few retrospectives of clubland in London recently, notably about The Blitz, legendary performance artist and club promoter Leigh Bowery and Fashion Outlaws, about denizens of the club, Taboo.

I see “Reunion 79:21” as a way of discovering more about some of the Black queer figures who may have been perceived as extras, but were, in fact, pioneers.

Name three of the most significant figures in the history of London Black queer clubland and why?

SW: Author and performer Valerie Mason-John [b. 1962] for their activism surrounding black lesbian club representation; DJ Chris McCoy [1971-2001] for being a revolutionary man, and the community love he engendered; DJ Mark Moore for his ability to connect strands of culture, music, fashion, and for his enduring kindness.

Gay City News’ audience would be interested in reading about some of the ways in which the London Black queer clubland scene had links to its counterparts in New York and other Black queer clubland U.S. capitals such as Chicago and Detroit. Please expound.

SW: In the early eighties, where the exhibition begins, Chicago and Detroit queer collectives were organizing underground raves where American musical forms — disco, hip hop, and house — were played. It was, in fact, DJ Larry Levan and the iconic Paradise Garage club that inspired London club impresario Steve Swindells to create (arguably) Central London’s first successful Black Queer club night, The Lift, one of the venues where his brother, Dave, took photos exhibited in Reunion 79:21.

In general, British clubs of that period, which in the exhibition is themed, “Finding the Night, 1979 – 1993,” enjoyed homegrown, post-Windrush [Caribbean-influenced] genres of “Northern soul,” “rare groove,” “Brit-soul,” “jazz-funk” and “lovers rock,” independently, in cliques.

By contrast, Steve Swindells’ choice of deejays played an eclectic combination of sounds inspired by both U.S. and U.K. music. The Lift’s motto, “All humans are welcome,” thus signaled a new era of clubbing that was akin to the diversity and flavor of Paradise Garage, just steered by the ever-evolving cultural mix that is London.

Seeing as Steve Swindells is white, has there ever been any objection, or critical response, from the Black community to his role as promoter of this iconic Black gay party, especially since other Black queer club nights like Bootylicious (photographed by Jason Manning) were also run by white promoters?

SW: I can only reflect history as it is. Many of those people who “objected” would not have had the same access to West End nightlife due to the racial politics at the time.

Does this exhibition have a virtual home where readers in New York, or anywhere outside London, may access some of the information and images included in the exhibition?

People migrate, so we want to hear stories from people who may have attended some of the clubs, and from those who are just interested. We have therefore launched a website that takes the exhibition into its third phase.

The first phase was the archiving component. We are in partnership with Westminster City Archives to ensure that commissioned videos and archival materials from the exhibition will have a public-access home in perpetuity.

Phase two is the exhibition, which is almost upon us; and we plan to tour the exhibition at some point.

We see our website, Phase three, as enabling a global portal for exchange: stories, events, and exhibitions related to clubland.

Collaborations are definitely sought, so please contact us.

Why is this exhibition so short?

SW: Because, like many New York residents know, Soho rents are high!

Reunion 79-21 – Revisiting Black Queer London Clubland | Great Pulteney Street Gallery, London | January 21-25

Nicholas Boston, Ph.D., is a professor of media sociology at Lehman College of the City University of New York (CUNY). Follow him on Twitter @DrNickBoston and Instagram @Nick_Boston_in_New York