The work of pioneering portrait photographer Lola Flash is the inaugural exhibition of a collaboration between Marian Goodman Gallery and Jenkins Johnson Gallery whereby over the coming 12 months the latter will periodically mount exhibitions on the third floor of the former’s location at 385 Broadway, in Tribeca.

Both galleries are members of the Art Dealers Association of America, and this collaboration, they say, “embodies the spirit of co-operation fundamental to New York’s contemporary art community.”

The retrospective exhibition, “Believable,” takes its name from a book of Flash’s work published in 2023 that was hailed as one of the “Best Photo Books of the Year” by Smithsonian Magazine.

Over four decades, Flash’s practice has evolved through multiple thematic series, showcasing persons and concepts that shaped culture and society, primarily in New York.

Flash, who uses the pronoun “they,” first came out with a series called “Cross Colour” that used the cross-processing technique of photo development to create images in which light and shadow are inverted, making it challenging, if not impossible, to discern the identities of their subjects.

The series emerged in the late 1980s and 1990s from Flash’s participation in queer cultural production such as ACT UP, the HIV/AIDS activist movement, and the Clit Club, legendary lesbian entertainment venue in the Meatpacking District of yesteryear. Several of the images were also taken in London, England, where Flash lived for 12 years beginning in the 1990s and earned a master’s degree from the London College of Printing, hence the intentional British spelling of the word “color” in the series’ title. One photograph, “Cow Girl,” shows a reclining, female-presenting figure, body dark, clad in a cowboy hat, bustier and gun holster that are all luminously white.

“I photographed my then partner, Vickie, in my bedroom, in London,” Flash says in their artist’s statement. “It was in 1999…Many of the folks I hung out with during this time were into BDSM and many of the photos during this period feature women in this kind of gear.”

From there, the exhibition traces the path of Flash’s portraiture into the 21st century. These are images produced in response to both social challenges and flights of the imagination.

The “[sur]passing” series are portraits exploring the significance of skin color — what Flash calls “the pigmentocracy” — in lived experiences around the world. A selection from this series, “Thato,” pictures a striking gender non-conforming subject whose medium-brown complexion blends nearly seamlessly into the color of the outfit they are wearing as they pose against a hopeful blue sky.

In the “surmise” series, the portraits are meant to upturn assumptions about gender. In the selection, “Miss Kimberly,” the subject crosses her arms and casts a determined stare sideways over a black turtleneck-clad shoulder. The red of her wig, her lipstick, and her driving gloves makes the portrait pop.

Women over the age of 70 passionate about their life work embody the theme of the “SALT” series. Represented here is an absolutely majestic portrait of Betye Saar, who at age 99 is one of a handful of doyennes of the art world still practicing. It shows the artist seated in her studio, with her work all around her, the hands she used to create them resting gently on her cane in front of her.

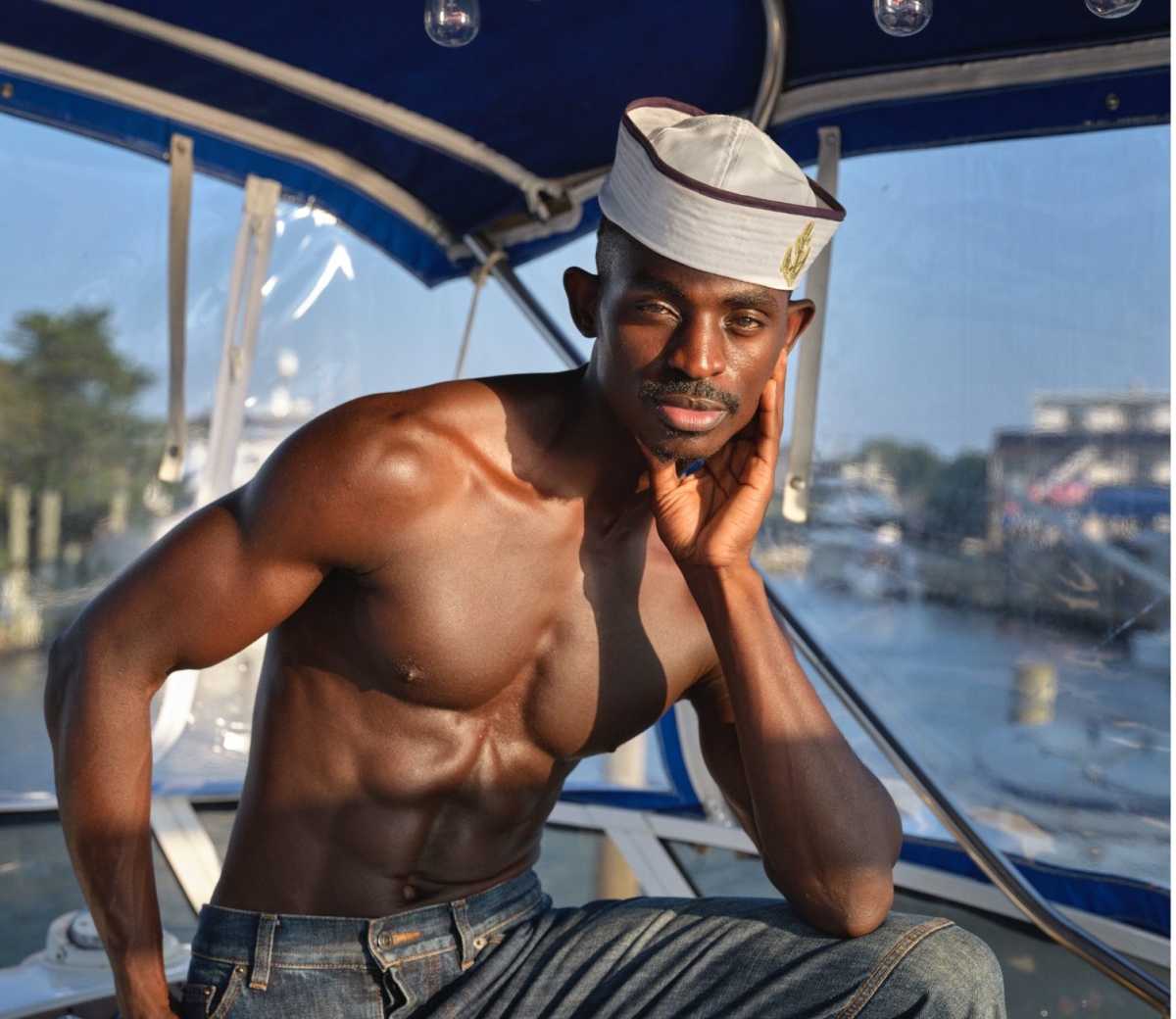

In the series “Unsung Fire Island,” Flash addresses experiences of explicit racism and implicit bias experienced by Black and brown people in queer havens. With the support of a BOFFO residency for artists on the island, Flash interviewed people and took their portraits, matching testimonies of encounters with microaggressions or stereotyping with portraits that prioritize individuality and subjectivity. After decades of summering on Fire Island, Flash was inspired by the nationwide (and international) racial reckoning brought about by the murder of George Floyd to explore the experiences other people of color have had residing or visiting there. The project was covered in a 2021 “New York Times” article that got many tongues wagging.

Represented in “Believable” from the “Unsung Fire Island” series is the portrait of “Emolsa,” whose six pack is as taut as his expression soft. The photograph reminds me of the hyper-sexualization Black men often experience in spaces dominated by white gay culture, and the ambivalence some of us feel utilizing it to pay the price of admission to some rarefied circles.

“Those guys out there are CEOs of this and that,” Flash says in the “Times” article, referring to Fire Island society. “And if we can get them to start thinking differently and embrace difference then a change will come.”

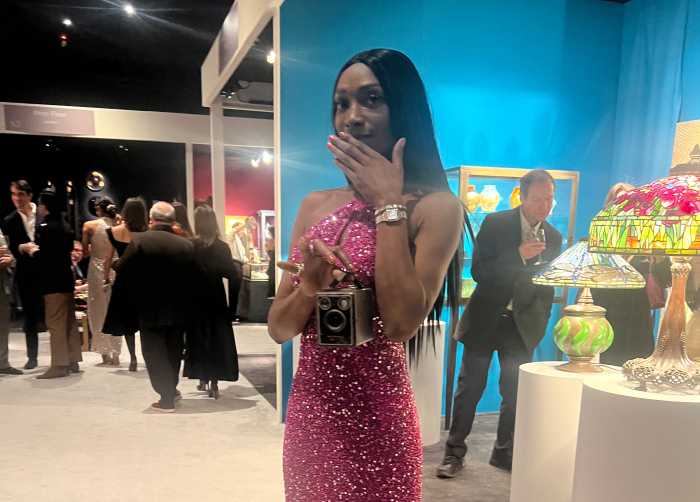

“Legends” is a series of portraits of queer cultural producers Flash considers trailblazers. In an artist’s statement, Flash explains that it showcases a diverse group of “actors, advocates, DJ’s, performers, and much more” whose work “clashed against societal norms.”

One portrait taken from it is of the director Robin Cloud. Cloud’s 2019 biographical TV miniseries, “Passing: A Family in Black and White” fascinatingly explores the phenomenon of Caucasian-appearing African Americans assuming a white identity. Cloud seeks out members of a branch of her own family who passed into whiteness generations ago and informs them of the truth. The series also understatedly overlays the silences and negotiations that queerness can entail for LGBTQ family members. The portrait Flash took of Cloud shows her gazing off-center to someplace, or someone, outside the frame, her hands raised, palms facing forward. She looks like she is attempting to either bringing calm or surrender to a situation.

In their most recent series, “syzygy, the vision,” Flash finally turns the camera on themself. It follows a space-suited alter ego shot in mundane public Earthly locations. The series engages with the concept of Afrofuturism. The series a “multi-dimensional contemplation [that] considers vast dimensions of intersectional disadvantages, cultural conflicts, and unsettling legacies,” Flash said in an interview with the Smithsonian.

“I Pray, Manhattan, NY” is a selection from “syzygy, the vision” that pictures Flash in an alter ego guise, sitting in a spotless, empty subway car that looks eerily futuristic. Flash is in a quasi-prayer pose. The self-portrait was taken in 2020 aboard an F train, which goes through Astoria, Queens, where Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani was at the time, since 2018, residing. In January, 2026, Mamdani, one of whose campaign promises was to reform public transportation, will take up residence in Gracie Mansion, the New York City mayor’s official residence. Is Flash’s portrait a prediction of this city’s future, come what may?

Believable | Jenkins Johnson Gallery at 385 Broadway, Manhattan | Until December 20, 2025

Nicholas Boston, Ph.D., is a professor of journalism and media studies at Lehman College of the City University of New York (CUNY). Follow him on Twitter @DrNickBoston and Instagram @Nick_Boston_in_New_York