This month, Gay City News takes a look at new releases by Troye Sivan and Beverly Glenn-Copeland.

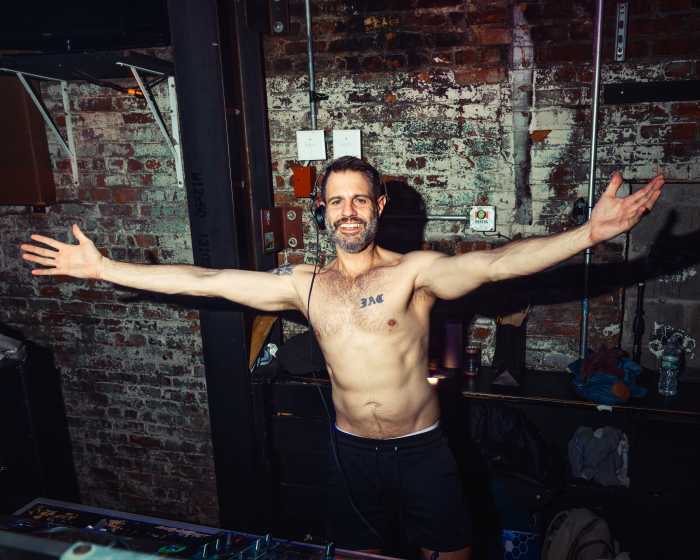

Troye Sivan | “Blue Neighbourhood: Deluxe Edition” | Capitol | Feb. 13th

When Troye Sivan released his debut album, “Blue Neighbourhood” in December 2015, he had already experienced a taste of celebrity. As a teenager, he found a large audience on YouTube. His gayness was part of his public presentation even before “Blue Neighbourhood” was released. Now that he’s 30, Capitol has issued a second deluxe edition of the album, with two bonus tracks: “Strawberries & Cigarettes,” originally released on the “Love, Simon” soundtrack, and “Swimming Pools.”

On most of “Blue Neighborhood,” Sivan’s voice holds back, with keyboards and drums supplying the drama. It feels like what it was: an album made by a very young man after the break-up of his first relationship, preparing to leave behind the Australian suburbs where he grew up. The lyrics are direct yet tentative: “Talk Me Down” promises “I want to sleep next to you, but that’s all I want to do.” Elsewhere, he sings “I was trying to be cool, I was trying to be just like you.” “Heaven” ponders the compromises inherent in love: “without losing a piece of me, how do I get to heaven?” “Fools” puts a nervous spin on dance music. Amidst a swirling background, Sivan regrets his indecisiveness.

The EDM and trap influences mark “Blue Neighbourhood” as a product of its time, as does the feature from Alessia Cara on a remix of “Wild.” Yet the album represents something that remains rare: queer youth speaking honestly about their experiences to a potential audience of millions. Heterosexuals, especially men, take for granted that the world will give them a platform to discuss their heartbreak. Although Sivan would go on to be more sexually frank, this is his starting point.

Sivan’s popularity hasn’t faded, but “Blue Neighbourhood” marked its peak. The album went platinum, but its two follow-ups, “Bloom” and “Something to Give Each Other,” have not even gone gold. “Youth” remains his only top 40 hit. It’s hard to avoid the suspicion that his gayness has placed a glass ceiling on his commercial success.

Beverly Glenn-Copeland | “Laughter In Summer” | Transgressive/PIAS

While listening to “Laughter in Summer,” distance collapses, as though one were sitting in the living room of Beverly Glenn-Copeland and his wife Elizabeth Glenn-Copeland. Recorded after Beverly’s 2024 diagnosis with dementia, it strips his music down to its barest essentials: voice, piano and flute. Despite a small discography, he’s performed in a variety of styles — his first two albums’ jazz-folk, the electronic “Keyboard Fantasies” — but “Laughter in Summer” delivers the most austere version.

Six of the album’s nine songs are duets between Beverly and Elizabeth. On the title track, she takes the lead, while he murmurs “la-da-da.” These are spontaneous performances, recorded live in the studio by the couple, accompanied by a choir. With only one exception, the recordings are first takes. Stark production accentuates the impact of Beverly’s voice, steeped both in classical lieder and Black American traditions.

Despite Beverly’s condition, “Laughter in Summer” is joyful and optimistic. “Let Us Dance” contains only five lines, but they establish the album’s spirit: “the day greets the dawn/the sun dances down beside/this road we are on.” The lyrics’ imagery refers to the seasons, as on “Every New”: “welcome the spring/the summer rain again.” They see aging and death as part of a natural cycle. On song after song, Beverly declares his devotion to Elizabeth. “Children’s Anthem” finds both him and her offering their wishes for the future. “blessings on our precious children/may they grow up strong and free.” Beyond the meaning for the Glenn-Copeland family, it’s a benediction for all of us, in a world growing ever more menacing.

“Middle Island Lament,” during which vocals are accompanied only by a flute, is a small departure from the piano-based music. “Laughter in Summer” cracks open with a countercultural idealism, expressing its feelings in an unadorned manner. The difficulties and humiliations that dementia always brings can wait for later; for now, Beverly and Elizabeth are happy to celebrate their love for each other.

“Laughter in Summer” closes as it begins, with a second version of “Let Us Dance Down the Road.” “Let us dance down the road,” sings Beverly, with Elizabeth answering his voice with a fainter echo. Performing in a call and response, they close the song with wordless vocals. This is as good as place as any to shut the door on a life of great accomplishments.