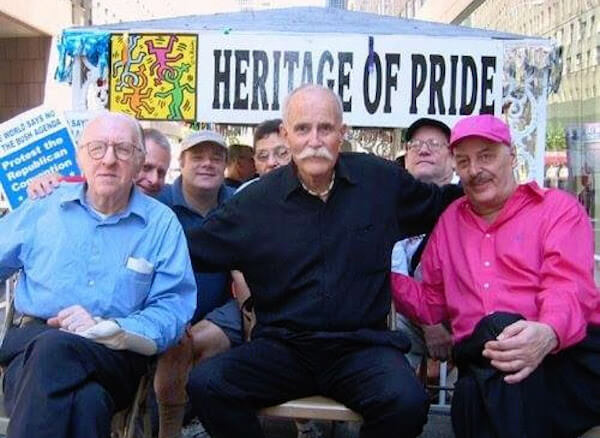

John James, who declined to be photographed in the 1965 Annual Reminder picket, in a recent photo. | PHILADELPHIA GAY NEWS

BY JEN COLLETTA | On July 4, 1965, John James traveled to Philadelphia to march among a group of gay and lesbian demonstrators calling for liberty for LGBT people. Nearly 50 years later, James is again surrounded by LGBT people in the City of Brotherly Love —this time in a very changed world.

Earlier this year, James, 73, moved into the John C. Anderson Apartments, an LGBT-friendly senior living facility in the heart of Philadelphia — more specifically, on South 13th Street in the Gayborhood section of town. The building, just one of a few affordable gay senior living complexes anywhere, is the largest publicly funded LGBT building project in the nation’s history. The complex is home to a vast cross-section of the LGBT elder community — businesspeople, artists, activists, researchers, social workers, and everyone in between — who lived through, and at times led, the birth and growth of the modern gay rights movement.

The spark that ignited that movement is typically traced to the June 1969 riots at the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street. But, four years earlier, a different sort of protest calling for LGBT freedom germinated on the steps of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall — fittingly, the birthplace of American freedom.

A veteran of pioneering 1965 Philadelphia demonstration looks back

What was dubbed the Annual Reminder march was conceived of by Craig Rodwell — who two years later founded the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in the West Village — and organized by pioneering activists such as Washington-based Frank Kameny as well as Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen of Philadelphia. The demonstration was set for Independence Day to call attention to the fact that gays and lesbians were denied the basic rights guaranteed to them in our nation’s founding documents.

At the time of the march, James was a 24-year-old working as a computer programmer at the National Institutes for Health. Having grown up in DC, he moved back there in 1963 after graduating from Harvard University. James’ father was a federal government anti-trust attorney and he followed in his footsteps in seeking work in public service after abandoning his initial idea of pursuing medicine.

“I was always interested in science and went to college intending to do pre-med but I decided it wasn’t for me,” he said.

James recalled that he began coming to terms with his sexuality in his early 20s and, after returning to DC, joined the fledgling Mattachine Society, what was then known as a “homophile” group whose Washington chapter was the brainchild of Kameny and Jack Nichols. James said he was usually just an observer at the group’s meetings.

“Jack went on to be a well-known gay writer but, at the time, he used a pseudonym, Warren,” James recalled. “His father was an FBI agent, and Hoover had a real thing about homosexuals. His father told him he’d kill him if the FBI found out about [his being gay], so we always used the name Warren. He and Kameny and some others came up with the idea for the demonstration.”

Noting he had never before participated in a public demonstration, James said, “It was kind of the thing to do. I went along and did it because that was the thing to do right then.”

James was then out to only a small circle of friends and family, so he was reassured that his chances of being outed by marching were slim since the demonstration was not in DC. He declined when organizers asked for his consent to be photographed at Independence Hall.

“I said no because I liked my job,” he recalled.

At the time, the prevailing policy in the federal government was to terminate “known homosexuals.” That policy foreclosed certain opportunities for James’ advancement.

“I never considered applying for a security clearance because they would’ve found out and that would have complicated things,” he said, adding with a laugh, “But, I didn’t want to do military work anyway, so not having a security clearance was one way to make sure I stayed away from that.”

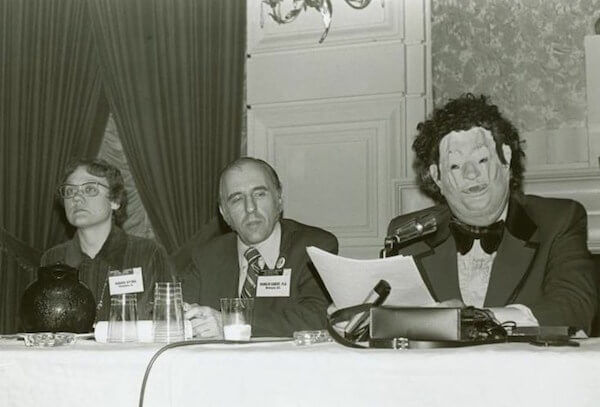

Barbara Gittings, one of the organizers of the Independence Hall pickets. | KAY TOBIN LAHUSEN/ WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The Annual Reminder organizers insisted that participants both dress and act professionally during the demonstration.

“We all wore suits and ties,” James said. “That was Kameny, that was his philosophy.”

About 40 people participated in the inaugural picket and marched for about an hour-and-a-half behind a police barricade, holding such signs as “Homosexuals should be judged as individuals” and “Homosexual civil rights.”

James recalled participants having “some degree of fear” about marching, but said they were met with no real pushback.

“People took it in stride,” he recalled. “I didn’t notice any expressions of either hostility or support. It turned out peaceful. We weren’t attacked by people in the streets or anything.”

James’ face stayed out of photos, though a picture of Gittings that ran on the front page of the Philadelphia Inquirer may have just missed him.

“I suspect my leg is showing in the picture,” he said. “But I’m not sure.”

Though James only participated in the 1965 event, picketers returned each year for the next four years, the final Annual Reminder demonstration taking place just days after Stonewall in 1969. James would likely have been surprised to know that the type of activism he undertook in 1965 would explode on the streets of New York just four years later.

“I knew there was a symbolic importance at the time, but it wasn’t necessarily the kind of movement I would have done myself if I hadn’t been asked, but yet again I wasn’t an organization person anyway,” he said. “So I went along with how Frank and Warren wanted to do it. My philosophy was a little different. Kameny’s was to pick one issue and do just that issue, where my idea was to mix all the issues — anti-war, gay rights, civil rights, whatever you had the opportunity to do.”

After leaving federal employment, James moved to the Haight-Ashbury section of San Francisco, where unfortunately events conspired to give him the opportunity to prove his commitment to multi-issue activism. As the HIV epidemic began ravaging that city in the 1980s, he founded AIDS Treatment News (ATN). Early on, the publication explored alternative medicine and experimental treatments and went on to publish more than 400 editions.

“When treatments were becoming available, no one wanted to cover it,” he said. “So we were talking to patients, doctors, scientists. That was my main project. I was never much into demonstrations so I think that, by far, my most important activism was AIDS Treatment News. That was my contribution.”

After years in San Francisco, that cradle of high tech entrepreneurship became unaffordable, and James packed up ATN and headed back east, deciding to settle in Philadelphia, where he had a number of colleagues and friends. ATN now operates as an independent project housed at Philadelphia FIGHT, an AIDS services group.

James reflected with some wonder on the city of Philadelphia’s plans to host a large-scale celebration next year to mark the 50th anniversary of the start of the Annual Reminders pickets.

“We never would have thought of any official recognition like that,” he said. “That would have been inconceivable. We were just happy to be more tolerated. We weren’t looking for anything out of the government besides just letting us live how we wanted to live and leaving us alone.”

Jen Colletta (jen@epgn.com) is a staff writer at Philadelphia Gay News, which is spearheading nationwide coverage of the annual October LGBT History Month.