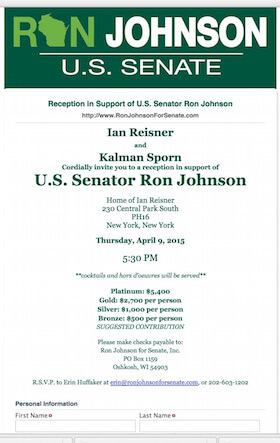

President Barack Obama signs his executive order barring anti-LGBT discrimination by federal contractors. | COURTESY: TOBIAS BARRINGTON WOLFF

First things first. President Barack Obama did his job this week, and the LGBT community is the better for it.

For the past several years — especially as continued Republican control of the US House made it clear LGBT job protections nationwide in the form of the federal Employment Non-Discrimination Act would not be enacted any time soon — Obama faced escalating demands to issue an executive order ensuring that companies profiting from taxpayer-funded government contracts do not discriminate.

For a time, the administration reiterated its desire to see ENDA become law, perhaps not wanting to take pressure off Congress on the nondiscrimination front. But when Republican House Speaker John Boehner insisted that even the Senate’s bipartisan approval of the bill last year would not sway him, the president perhaps judged it was no longer politically credible for him to hold out for a legislative fix.

The order he signed on Monday of this week does not, of course, grant blanket job protections for all LGBT workers, but it’s no small potatoes, either. Contractors covered by the order employ an estimated 28 million Americans, or just under 20 percent of the total fulltime workforce. That’s meaningful clout the US government exercises in the labor market, one that is likely to have significant spillover in creating competitive pressures on companies not participating as federal contractors.

The president is to be praised, however, not simply for issuing the order — frankly, we should have seen it earlier — but for doing it in the right way. As news surfaced last month that he intended to move forward, Obama faced intense pressure from religious conservatives and Republicans to carve out a broad religious exemption that faith-based social service agencies and perhaps other entities could use to opt out of the nondiscrimination provisions.

Religious exemptions have become a hot button culture war wedge of late in America, especially in the wake of the Supreme Court’s radical June decision in the Hobby Lobby case that said even corporations are eligible as “people” to claim such outs. Within the LGBT community, there had already been a roiling debate over the breadth of the exemptions in ENDA, which even those among our leaders supporting the provisions admitted could allow religiously-affiliated organizations, including hospitals, universities, and social welfare organizations, to fire LGBT staff members carrying out all manner of jobs — from janitor to professor, from nurse to secretary.

Religious organizations have always enjoyed some degree of exemption from civil rights law since at least some of their employees carry out constitutionally protected religious practice. It may seem as though that makes it difficult to draw a clear, bright line, but as attorney Evan Wolfson, the founding executive director of Freedom to Marry, pointed out on MSNBC recently, “We worked this through right 50 years ago this year,” with the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which “got the balance right.”

To the extent that religious groups claim an exemption it should be to ensure that members of their faith carry out faith-related activities. That was how the ’64 Act was written and how it applies to prohibited racial, sex, and religious discrimination. And that principle was carried forward into President Lyndon Johnson’s executive order the following year barring discrimination by government contractors.

And so it was fitting that Obama relied on what “we worked… through right 50 years ago” and amended Johnson’s contractor order from 1965. It was the appropriate thing to do and also had the virtue of being politically canny. For those who spent weeks demanding broad religious exemptions and were at the ready to fault him, the challenge they face is explaining why discrimination against LGBT Americans should not be treated exactly the same way as bias aimed at other groups.

Some observers have noted with concern that President George W. Bush amended the Johnson order in 2002 to broaden the rights of religiously-affiliated government contractors to establish a religious test for their employees. They have, with good reason, asked whether Catholic Charities, for example, could say a job must be filled by a fellow Catholic and then argue that no sexually active gay person can call themselves a practicing Catholic.

Some have called on the president to claw back the Bush order, but that is a very tall political order and one that sets up the unsettling prospect that presidential executive orders could soon become short-term vehicles with an expiration date every four or eight years. And, as Arthur S. Leonard notes in his analysis about the new executive order, the Hobby Lobby ruling raises similar risks that the principle of religious exemptions might be abused to the detriment of LGBT people. Those risks would not be mitigated by jettisoning Bush’s amendment to the contractor order.

The best news about Hobby Lobby is that it was not one based in the Constitution but rather was an interpretation of the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). Damage that was done through legislation can be fixed through legislation. Now that the Human Rights Campaign, ENDA’s chief Capitol Hill lobbyist, has agreed with other leading advocacy groups that ENDA’s over-broad exemption must be eliminated, the bill’s redrafting can also take account of the Supreme Court’s reading of RFRA in the Hobby Lobby decision. Strong employment protection provisions on par with those in the 1964 Act can go far in curing both the Hobby Lobby and the Bush amendment problems.

Which leads me back to my argument from several issues back. If the Civil Rights Act is the best model for our employment rights, it’s also the best vehicle for tackling discrimination overall. We need to be given the full protections of the ’64 Act across the board — in housing, public accommodations, access to credit, as well as employment. We knew how to do this 50 years ago.