The lore of a Hawaiian king and his lover — an important historic figure in his own right — was almost lost to time. Present-day researchers and artists in Hawai‘i are intent on breathing new life into their story.

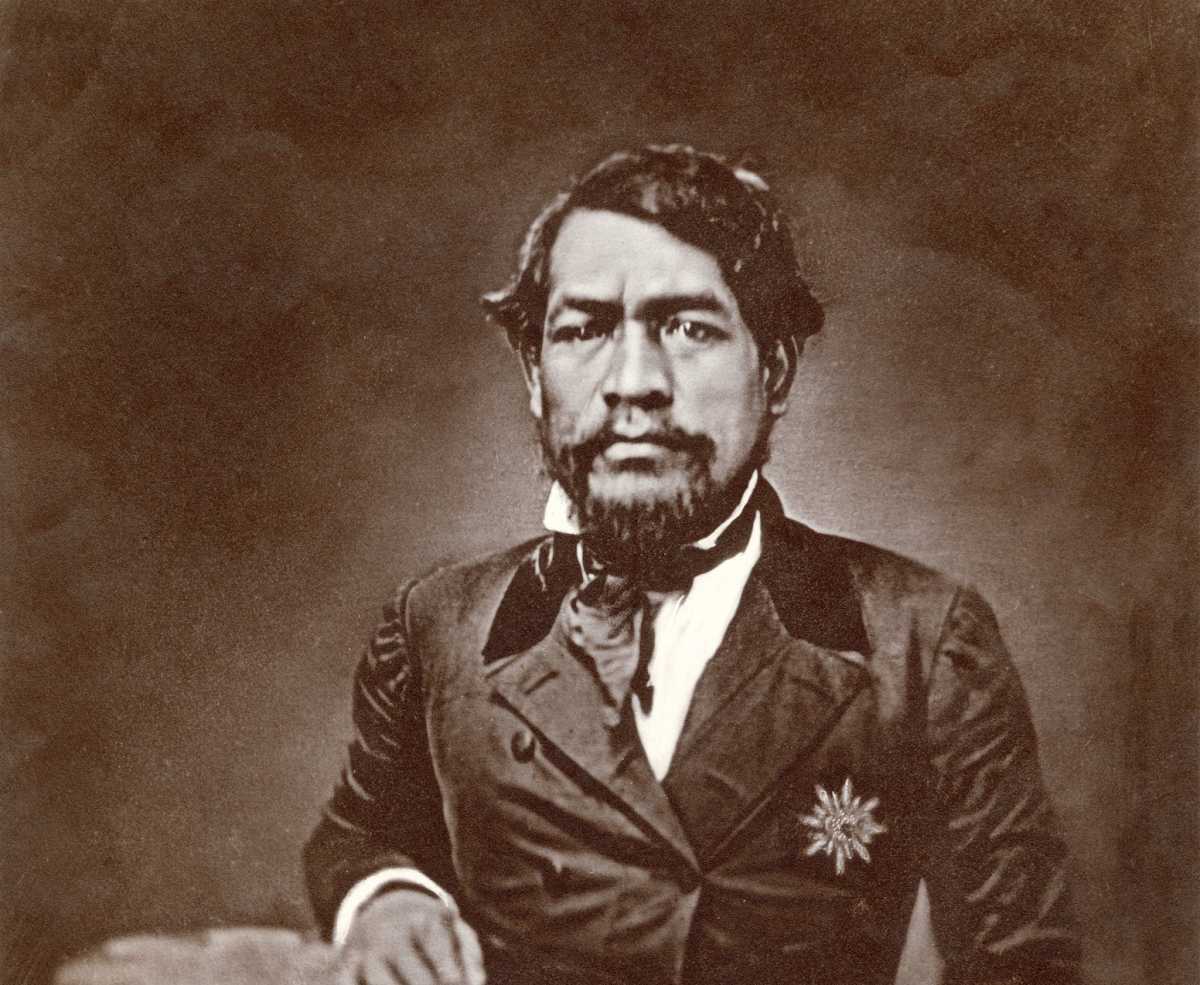

The 19th century relationship between King Kamehameha III and Kaomi Moe was largely forgotten across the islands until that chapter of the past was revived in recent decades through academia and art.

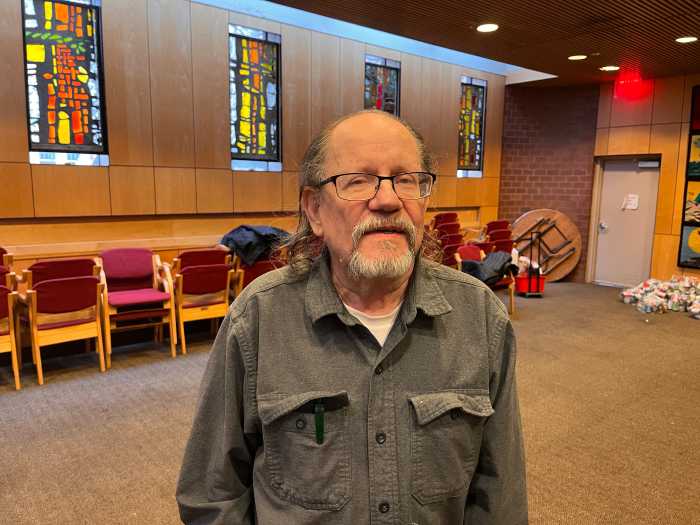

Dean Hamer, a researcher and filmmaker in Haleʻiwa, O‘ahu, first learned of Kaomi in the 1990s when American society was debating the legalization of same-sex marriage.

“There were some articles that mentioned the relationship between Kaomi and Kamehameha III as an example of how same-sex relationships had been very much accepted in early Hawai‘i,” he said.

Hamer depicted Kaomi as a significant historical figure who was ignored in subsequent years due to his queer relationship.

“It’s really important to celebrate Kaomi for who he was — not just because he had a same-sex relationship but because he did important things,” he said.

Notably, aikāne, the Hawaiian term for an intimate same-sex partner, can be traced in written sources as far back as 1776 from Captain James Cook’s journals, according to an article in the National Library of Medicine by R. J. Morris.

“Among these aikane were several who acted as intermediaries between the sailors and the Hawaiians, and whose influence and conduct profoundly affected the course of events at Kealakekua Bay, where Cook was killed in February, 1779,” Morris wrote.

As Hamer tells it, Kaomi was born on Maui in the early 1800s — a transition period for Hawai‘i, in which the newly-established kingdom was absorbing the influences of foreigners and Christian missionaries.

Sources differ on whether Kaomi’s father, Moe, was from Tahiti or Bora Bora, but his mother, Kahuamoa, was a Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) woman, per The Gay & Lesbian Review. Hamer said Kaomi’s uncle taught him how to read and write with hymnals.

He explained that Kaomi proved to be of quick wit, and his uncle appointed him as head of a school. The young man caught the attention of the Rev. Hiram Bingham, a missionary who arrived in Hawai‘i between 1819 and 1820, according to the Punahou Bulletin. Bingham made Kaomi part of his flock of Kānaka Maoli youth who proselytized across the islands, Hamer said.

Kamehameha III — born with the name, Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa Kuakamanolani Mahinalani Kalaninuiwaiakua Keaweawe‘ulaokalani — became king in 1825, per Encyclopaedia Britannica. He was first introduced to Kaomi because of his traditional healing abilities, then the two became aikāne.

“They’re having this affair, and everybody knows about it,” Hamer said.

Because of Kamehameha III’s young age, Queen Ka‘ahumanu served as acting regent. She knew about the affair as well and cautioned against it, Hamer said.

By the early 1830s, Kamehameha III stepped into his power, and Ka‘ahumanu died.

“He makes the relationship with Kaomi official,” Hamer said. “He says, ‘Kaomi is now my Mōʻī kuʻi, aupuni kuʻi: co-ruler and co-chief, co-king, even. And this is a big deal.”

Hamer explained that other chiefs had aikāne of their own, but none had been elevated to such a position. Guards protected Kaomi, who was able to disperse land to the people and lend on behalf of the government. Kamehameha III rescinded some mandates by Ka‘ahumanu that had forbidden hula and the drinking of ‘awa, or kava.

“Most of what we know about this is from missionary letters,” Hamer said, and they were extremely unhappy.

At the behest of those missionaries, a Christian chief was sent to abduct Kaomi and bring him to Honolulu for execution, though Kamehameha III hurriedly saved him.

Their romantic relationship allegedly ended, and, “after that, (Kaomi) just disappeared from history,” Hamer said.

However, on Hawai‘i, an effort to shed light on his legacy has caught hold.

Enter Aloha Kāua: a play written by Noalani Helelā and performed at O‘ahu’s Palikū Theatre and Maui’s ʻĪao Theater last year. The production depicted the remarkable “Time of Kaomi.”

“Words cannot express how meaningful it was to me to be a part of reviving this important piece of history, especially through theatre,” said Taurie Kinoshita, artistic director of the Hawai‘i Conservatory of Performing Arts. “It can have the greatest impact because you are there, living and breathing with the actors.”

Taurie Kinoshita wore several hats for Aloha Kāua, directing, designing costumes, and serving as prop master. She considered the story to be a crucial — but neglected — piece of history.

“The history of Kauikeaouli and Kaomi in general has been too often overlooked,” Kinoshita said. “Many, many people were surprised to hear about it.”

She explained in her director’s note that Helelā embraced some artistic deviations from the actuality of Kamehameha III and Kaomi’s relationship. For example, the use of the throne, palace and crown in the production was metaphorical, and Ka‘ahumanu “famously wore yellow (or stripes),” Kinoshita wrote.

But an inherent fact still stood.

“Almost two hundred years ago, two young men fell in love,” Kinoshita wrote. “Helelā’s play is the somewhat fictive and yet totally truthful story of two men who change because of each other and, together, face a changing world.”

She witnessed the impact that Aloha Kāua had on its audience, with a respectable number of attendees watching the performance. However, prejudices persist.

“We did have a few too many people leave at intermission after the shared kiss by Kauikeaouili and Kaomi,” Kinoshita told Gay City News.

Even — and especially — in the face of bigotry, the tale must live on.

“This story is vital in any time period,” Kinoshita said. “But with the current political climate, it is even more important.”

She encourages the queer community to follow in Kaomi’s footsteps.

“Like Kaomi, we must and will speak out,” Kinoshita said.

Author’s note: Writer Megan Ulu-Lani Boyanton identifies as Kanaka Maoli.