Justice Anthony Kennedy. | UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT

Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy is considering an application from the National Organization for Marriage (NOM) –– formed specifically to oppose same-sex marriage advances –– to put a stop to weddings that began in Oregon on May 19. That’s when US District Judge Michael McShane ruled that the state’s ban on marriage by gay and lesbian couples violated the Due Process and Equal Protections Clauses of the Constitution’s 14th Amendment.

The Supreme Court accepted the NOM application on May 28, and the following day Kennedy sent parties to the case word that all responses were due at noon on June 2.

Ruling that state accepted two weeks ago suddenly faces uncertain fate at Supreme Court

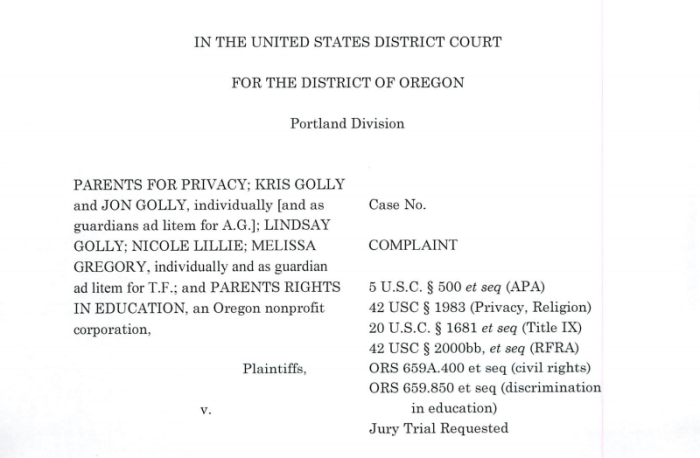

Neither Governor John Kitzhaber nor Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum, both Democrats, defended Oregon’s statutory and constitutional same-sex marriage ban in the lawsuit McShane heard, and NOM had scrambled to block the judge from issuing his order. Just hours before he ruled, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the group’s emergency motion to prevent him from issuing a decision until an appellate panel could hear its appeal of McShane’s decision to deny it intervenor status in defense of the marriage ban.

NOM based its petition to intervene on the argument that it had members in Oregon who have standing to intervene, but must remain anonymous for their own protection. The group cited Supreme Court rulings that allowed the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to file actions on behalf of anonymous members during the difficult early years of the civil rights movement in the 1950s.

In his marriage ruling, McShane found for the plaintiffs –– four same-sex couples seeking either marriage or recognition of their out-of-state marriage –– on their unopposed summary judgment motion.

“The case, in this respect, presents itself to this court as something akin to a friendly tennis match rather than a contested and robust proceeding between adversaries,” he wrote.

In analyzing the plaintiffs’ claims, McShane weighed them against arguments made by supporters of marriage bans in lawsuits in other states.

He rejected the idea that a 1972 Supreme Court ruling saying that because of a lack of a “substantial federal question,” it would not hear a gay couple’s appeal of a Minnesota Supreme Court decision denying their right to marry remained binding. Subsequent high court rulings on gay rights issues, including marriage, had rendered it obsolete, McShane found.

Even though he acknowledged that a recent Ninth Circuit panel found that heightened scrutiny should be applied when sexual orientation discrimination claims are alleged –– an approach that places a higher than usual burden on the state in justifying laws under challenge –– McShane concluded that the Oregon ban could not even survive the most deferential form of review. There was no rational basis for the denial of marriage rights to same-sex couples, he found.

Kennedy –– or the full court, should he decide not to rule on his own –– will consider a number of arguments NOM has made. First, citing the NAACP cases from 60 years ago, it claimed McShane erred in denying the group intervenor status. The anonymous individuals in Oregon it represents, NOM asserted, include a county clerk, a wedding services provider, and a voter who supported the Oregon marriage amendment when it was on the ballot a decade ago. The group argued the three have individual standing but have not been named in order to protect them from harassment or retribution.

McShane also erred, NOM argued, because he ruled prior to the Ninth Circuit hearing argument on the group’s appeal of his denial of intervenor status. The judge ruled, the group pointed out, without anyone arguing on behalf of the constitutionality of the state’s marriage ban.

McShane, NOM also argued, should have stayed his order pending appeal of it to the Ninth Circuit. Since the Utah marriage equality ruling in December, stayed the following month by the Supreme Court, all of the subsequent federal marriage rulings have been stayed –– except for the May 20 decision in the Pennsylvania case, which like the Oregon case, is not being appealed by the state.

The Supreme Court’s decision to stay the Utah ruling was a clear signal, NOM asserted, that it is reserving final say on the issue to itself and doesn’t want marriage equality forced on states by lower federal courts.

The group also claimed that the 1972 precedent from the Minnesota case is still binding, a perspective that has little support among observers or in the long string of recent federal marriage rulings –– all of which have noted the way other Supreme Court rulings have changed the judicial landscape.

Finally, NOM argued that the case before McShane was basically a sham, since nobody was the defending the state’s existing law and policy. No true “controversy” was at stake, a constitutional requirement when courts agree to decide cases. It should be noted, however, that in all the other recent marriage rulings, strenuous defense mounted by the state under challenge did not change the outcome.

In considering a stay, the high court looks at the likelihood that at least four justices would vote to hear the Oregon case, either on the merits or on the subsidiary question of NOM’s right to intervene; the likelihood that the court would overrule McShane on either of those questions; and whether the balance of irreparable harm that the two sides can show favors the state –– even though, of course, the state itself is not challenging the marriage ruling.

NOM has probably gambled correctly on there being four justices willing to review McShane’s marriage ruling and/ or his ruling on intervention by the group.

NOM asserted that in last year’s Defense of Marriage Act ruling, Kennedy made a federalism argument –– the US government could not override a state’s decision as to who was legally married. In Oregon, it argued, McShane turned that formulation on its head by dictating to a state what its marriage policy should be. Oregon’s concern for the well-being of children, who, NOM claimed, should be raised by different-sex married couples, provides the rational basis that McShane overlooked in striking down the marriage ban.

In terms of irreparable harms, NOM claimed that every same-sex marriage affronts Oregon’s sovereignty, while the plaintiff couples suffer no irreparable injury from simply having to wait for a final Supreme Court decision on marriage.

NOM has put together a very competently constructed document in most respects, and it would not be altogether shocking if Kennedy either grants a stay or refers the issue of the full court, which could then grant a stay.