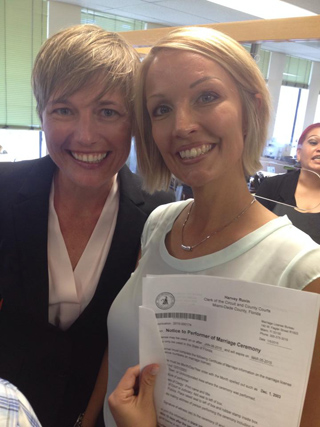

State Senator Jim Dabakis, Utah's Democratic Party chair, and partner Stephen Justesen, were among 35 couples married by Salt Lake City Mayor Ralph Becker in December. | TWITTER.COM

As is typically the case, oral arguments in Utah’s appeal of a December US district court decision ordering the state to allow same-sex couples to marry offered no clear indication of the three-judge panel’s views on the merits. Perhaps the most surprising outcome of the session, however, was the possibility the panel might not rule on the merits at all.

On more than one occasion during the April 10 arguments, which ran to just over an hour, the three judges from the Denver-based 10th Circuit Court of Appeals raised questions about the standing of Utah’s governor and attorney general to appeal District Judge Robert Shelby’s order. And one judge suggested that perhaps Shelby should not have decided the case on a summary judgment motion but rather held a trial to resolve disputed facts.

Shelby issued his order on December 20 and refused to stay his decision pending appeal, something the 10th Circuit also declined to do. By the time the Supreme Court issued a stay on January 6, more than 1,300 same-sex couples had married.

At 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, surprising questions about “standing,” need for a trial on disputed facts

It will likely be months before the appeals panel issues its ruling, and next week, on April 17, the same three judges will hear oral arguments in Oklahoma’s appeal of a similar district court ruling. The panel could choose to combine the two cases into one opinion.

Despite much that is unknowable regarding the views of the panel’s three judges, their questions and the dialogue between them and the attorneys for both sides provide some insight into their thinking.

The issue of standing, though not widely understood outside the legal community, occupied center stage last June when the Supreme Court ruled in the challenge to California’s Proposition 8. In that case, the governor and attorney general did not defend the 2008 voter referendum, and the high court found that the group that had appealed the district court decision striking down Prop 8 –– composed of the measure’s official proponents –– lacked standing to do so. Standing is a principle in federal constitutional law that requires that a party filing a lawsuit or seeking an appeal have a personal stake in the outcome of the case, not merely a theoretical or generalized interest.

In marriage equality cases, plaintiff couples seeking to marry clearly have standing to file suit against a public official, such as a county clerk, who refuses to issue them a license. Courts are divided, however, on whether they can file suit against a state governor or attorney general, since neither plays a direct role in issuing licenses or administering the state’s marriage laws. This issue can then turn into a question of standing if the governor or attorney general appeals a ruling against the state.

In the Utah case, the Salt Lake County clerk, who denied licenses to the plaintiffs, was a defendant in the trial but she did not join in the appeal. Gene Schaerr, who argued the appeal, presented himself as representing Republican Governor Gary Herbert and Attorney General Sean Reyes, the governor’s appointee.

It was the appellate panel –– and not the two parties in the case –– who raised the question of standing. Peggy Tomsic, who represented the plaintiffs, agreed with Schaerr in arguing there was no problem with standing. The governor and the attorney general, she pointed out, have ultimate supervisory authority over the county clerks and also over those agencies that face the question of recognizing same-sex marriages from other jurisdictions.

Despite the discussion about this issue –– and the fact that courts have dismissed marriage equality cases when plaintiffs have sued only the governor and attorney general, but not the official with direct authority for issuing licenses –– it seems unlikely the appeals panel would shy away from a ruling on the merits based solely on “standing.”

The question whether Herbert and Reyes have standing is a closer one than in the Prop 8 litigation, since in California it was a private party who was appealing. Surely, a state’s chief executive and chief law enforcement officer have a direct interest in appealing a trial court’s ruling that state constitutional and statutory provisions violate the US Constitution.

Standing was also an issue in the Supreme Court’s consideration of Edie Windsor’s successful challenge to the Defense of Marriage Act’s ban on federal recognition of her marriage to her late spouse, Thea Spyer. There, the high court asked whether the US solicitor general had standing to appeal Windsor’s win in the lower court, a ruling the Justice Department agreed with. Ultimately, the court found that the government does have a real interest in getting a binding Supreme Court ruling when a lower court declares a federal statute unconstitutional. The same logic should hold in the Utah case.

The other issue that came up during argument that could prompt the panel to defer a ruling on the merits was the question of whether there were disputed facts that should have been resolved in a trial prior to Judge Shelby’s ruling.

Since the DOMA ruling came down, only one federal judge among the many who have ruled in favor of marriage equality –– District Judge Bernard Friedman in the suit against Michigan’s gay marriage ban –– held a trial rather than ruling on constitutional grounds in response to a summary judgment motion. In Michigan, the trial centered on expert testimony from both sides about the potential impact same-sex marriage has on child-rearing outcomes. Friedman, in his opinion, concluded that the state’s witnesses on this issue were “unbelievable.”

If the 10th Circuit panel, however, finds disputed issues need to be resolved, it could send the case back to Judge Shelby with directions to hold a trial.

As in Utah, the other federal judges who have ruled in marriage equality cases since last summer ––in Oklahoma, Texas, Illinois, Virginia, Ohio, Tennessee, and Kentucky –– have taken the position that the issue can be decided as a question of law based on undisputed facts or, perhaps more accurately, based on a finding that even if the state is correct in its factual assertions, they do not justify denying same-sex couples the right to marry.

Significantly, Schaerr sent a letter to the appellate panel several days before the arguments stating that though the findings of a child-rearing study by University of Texas sociologist Mark Regnerus –– discounted as “unbelievable” by Judge Friedman in his Michigan decision –– were cited in Utah’s brief, they were not critical to the state’s case.

On the merits of the case, review of an audiotape of the arguments suggests it is unlikely a unanimous decision is in the offing. Judge Carlos Lucero, appointed to the court by President Bill Clinton, indicated in his questioning and comments that he likely supports the plaintiffs’ position, while Judge Paul J. Kelly, Jr., who was appointed by President George W. Bush, seemed more disposed toward the state’s position, though he posed many fewer questions, making it harder to discern his views.

The tiebreaker may end up being another Bush appointee, Judge Jerome A. Holmes, who questioned both sides quite sharply, making it difficult to predict where he will come out.

The judges seemed to agree the threshold question is what level of judicial scrutiny is appropriate to deciding the case. In a 2008 decision involving a lesbian’s claim that a law enforcement official discriminated against her in refusing to enforce an order of protection, the 10th Circuit established a precedent that sexual orientation is not a “protected class” under the Equal Protection Clause. Since federal appellate courts follow precedent already established in their circuit, the panel hearing the Utah marriage case would –– all things being equal ––be bound to subject the gay marriage ban to the least demanding level of scrutiny: the rational basis test, under which the plaintiffs must show the state has no conceivably rational justification for its policy. The panel could apply a more stringent standard only if legal developments since 2008 mandate it or if the case involves something other than just a sexual orientation discrimination claim.

A central issue during argument was whether last year’s DOMA ruling established a higher standard of review. The resolution of this question may prove critical, since at least one of the three judges –– Kelly –– suggested the Utah ban could survive rational basis review.

But, as the arguments made clear, it is not easy to predict how debate over the appropriate standard of review will be resolved. That, in good measure, is due to the way in which Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy crafted his majority opinion in the DOMA case. Eschewing the typical categories used in distinguishing between rational basis and heightened scrutiny cases, Kennedy did not state whether the DOMA case involved a fundamental right to marry or if sexual orientation is a suspect classification –– either of which would demand a heightened standard of judicial review. Rather, he treated it as a case in which Congress discriminated against same-sex couples by excluding them from the recognition of their state-law marriages in a way that deprived them of numerous federal rights and benefits.

DOMA was not just a sexual orientation discrimination case, the Supreme Court found, but also one of intentional unequal treatment of a defined portion of the population, having direct and wide-ranging adverse effects. None of the arguments made to justify the policy choice Congress made in 1996 were sufficient to justify the magnitude of what same-sex couples were denied, according to the high court. Instead of drawing from the language the court uses in racial and sex discrimination cases, Kennedy’s analysis of DOMA was tailored to the particular issues the case raised.

The lower courts, accustomed to long established doctrinal categories, have struggled with applying the precedents established by Kennedy, not only in the DOMA case but in two other big gay rights rulings –– on sodomy in 2003 and in 1996 regarding Colorado’s anti-gay Amendment 2. Still, the DOMA ruling clearly suggests something like heightened scrutiny. Kennedy referred disparagingly to “second tier marriages” robbed of their “dignity” because they enjoyed state but not federal recognition, and wrote about the specific stigma and burdens imposed upon children whose parents’ marriages were not recognized. As in his 1996 Colorado opinion, Kennedy argued that any state policy that, on its face, discriminates against a distinct group of people must have a legitimate policy justification and must be shown to be necessary to achieving that legitimate goal.

Under such an approach, if the state argues that families headed by a husband and a wife provide the “best’ setting for raising children, it must show not only that this policy concern is legitimate and well-founded, but also that barring same-sex couples from marrying contributes to that goal. Schaerr was reduced to arguing that allowing same-sex couples to marry sends subtle messages to boys that undermine their masculinity and discourage them from marrying women, speculation that is, at best, a hypothesis.

On behalf of the plaintiffs, Tomsic argued that if there is a constitutional right to marry, no amount of unproven speculation can trump that right. The state should have to show that allowing same-sex couples to marry would have some sort of deleterious social effect, something not evident in the decade since marriage equality took effect in Massachusetts. The justification Utah put forward, Tomsic pointed out, is the same sort of rationale rejected by the Supreme Court last year in the DOMA case.

In fact, Justice Antonin Scalia, in his DOMA dissent, saw Kennedy’s approach as leading ineluctably to a constitutional right for same-sex couples to marry. Every federal trial judge who has ruled on marriage equality since then has agreed, a number of them quoting Scalia. If the 10th Circuit ends up being divided on this question, it will be the first time since last June that any federal judge has not reached that conclusion.

However the 10th Circuit comes down in the Utah case, there is a good chance it will not be the last word. Should the governor and attorney general’s standing be denied and Governor Herbert prove unable to have the full 10th Circuit or the Supreme Court reconsider that ruling, Judge Shelby’s decision would stand as unappealed and same-sex marriage would resume in Utah.

If the case is sent back to Shelby for trial, this litigation could become moot as another circuit ruling gets to the Supreme Court and the question of marriage equality nationwide is settled in that way.

And if the panel rules on the merits, the losing side will undoubtedly seek either rehearing by the full circuit or Supreme Court review. If Utah prevails, the case could end there, with the high court denying an appeal by the plaintiffs. Should the plaintiffs win at the 10th Circuit and their case go to the Supreme Court, their victory, momentous in the short term, would, like Edie Windsor’s victory at the Second Circuit in October of 2012, be merely a prelude –– and an historical footnote –– to how the Supreme Court settles the underlying question.