Evgeniy Tkachuk in Liubov Lvova and Sergei Taramajev’s “Winter Journey.” | FILM SOCIETY OF LINCOLN CENTER

“Creative Freedom through Cinema,” a sidebar to the new Romanian film series at Lincoln Center, features two queer offerings — one fiction, one documentary — about LGBT life in Russia made in that county. The screenings, on the afternoon of December 6, are followed at 5 p.m. by a panel discussion comparing gay rights in Russia, Romania, and the US, featuring writer Andrew Solomon.

The feature film, “Winter Journey,” written and directed by Liubov Lvova and Sergei Taramajev and screening at 1:30 p.m., takes its title from a composition by Schubert. Eric (Aleksei Frandetti) is a gay opera singer preparing for an important audition. He first encounters Lyoha (Evgeniy Tkachuk) on a bus one day when the other man starts a fight and takes his phone. The film follows both men separately after this initial encounter.

Eric, taught discipline by his singing instructor, is uptight and gets drunk to counter his anxiety. The reckless Lyoha ekes out a life on the streets by stealing a car radio, food, and a dog. Lyoha reconnects with Eric at a wild birthday party Eric attends with some gay friends. Lyoha realizes that Eric has access to money and may offer him an escape from his financial troubles. The fact that Eric is smitten with Lyoha helps the bad boy exploit his new friend.

Romanian film festival pauses to feature Russian films on LGBT life, rights under Putin

“Winter Journey” is an intriguing character study, even if the storyline is unsurprising. The filmmakers take their time getting the two main characters together, but once they do the film becomes more absorbing, even intense. Eric is completely taken with the handsome, seductive Lyoha, despite the petty criminal’s unsavory side. An episode involving the guys high and dancing at a nightclub is a particularly stylish sequence, providing a nice contrast to the chilliness and atmospheric realism of the rest of the film.

Tkachuk, magnetic in making an unlikeable character attractive, conjures the impish nature of a young Malcolm McDowell. As Eric, Frandetti commendably captures his character’s longing for the dangerous Lyoha. “Winter Journey” is a compelling portrait of contemporary queer life in Russia.

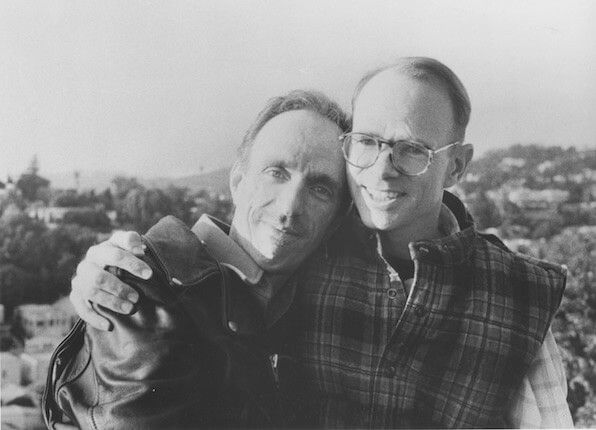

Pasha Romanov and an anonymous LGBT youth in Pavel Loparev and Askold Kurov’s “Children 404.” | FILM INITIATIVE/ COURTESY: CINEMA POLITICA

“Children 404,” which screens at 3:30, is an important documentary about LGBT youth. Directed by Pavel Loparev and Askold Kurov, the film is fascinating, maddening, and inspiring as it shows the trials and tribulations facing queer teens in Russia today.

In response to the 2013 law that forbids “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relationships to minors,” Elena Klimova founded a social network website, Children 404, to encourage LGBT youth to come out, tell their stories, and find support. Each contributor is asked to include their photo, with their eyes or face covered with the familiar Internet message “404 error — page not found,” a way of emphasizing their “invisibility in society.”

The film narrates 45 “anonymous” stories (only a few of the subjects are identified) that show the range of queer youth experiences in Russia. Some kids describe being bullied and harassed at school. One explains that the “propaganda law” means he could be fined for just going to school. While several talk about being called names and beaten up, one teen says she is forced to change for gym class in the toilet, having been banished from the locker room. Their stories meld together in the voice-over, emphasizing the secrecy most of them must maintain.

On the positive side, some teens embrace their sexual identity. One asserts, “I am homosexual. I am normal,” and others discuss becoming aware of their sexuality and accepting it. Some interviewees, who dare to appear on camera, talk about wanting to find a boyfriend and share a “normal” life. One teen, Pasha, even talks about eventually wanting kids, an aspiration that elicits particularly strong backlash from ultra-conservative Russians. Pasha is planning to move to Canada and study journalism.

Pasha Romanov in Pavel Loparev and Askold Kurov’s “Children 404.” | FILM INITIATIVE/ COURTESY: CINEMA POLITICA

Sadly, other interview subjects are self-hating, troubled in coming to terms with their sexual identity in a country where it is illegal. They wonder, “How do you accept who you are?” A few talk about suicide. Their despair makes evident exactly why a safe space like Children 404 is so needed in Russia.

One woman in the film insists parents should be educated about how to love their LGBT kids. When Pasha is seen being cared for by his loving, accepting mother, it offers a hopeful example.

The drama in “Children 404” reaches a peak when Pasha holds up a poster about gay rights in a Moscow square. He and a man harassing him about his poster are both quickly taken into police custody. This moment of activism is the film’s most resonant moment, making concrete Klimova’s assertion that “Sitting quietly does not equal security.”

“Children 404” provides critical insight into how LGBT youth cope with the oppressive burdens they face in Russia and cannot help but engender profound empathy among its viewers.

CREATIVE FREEDOM THROUGH CINEMA: Making Waves: New Romanian Cinema 2014 | Film Center of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater | 165 W. 65th St. | Dec. 4-8 | Each screening, $14.50; filmlinc.com