John Lewis, the Georgia veteran congressmember and civil rights giant who died at age 80 on July 17, was also a giant of an advocate for LGBTQ equality. That, of course, was but a tiny corner of his extraordinary life as a social justice champion.

In 1996, he was one of only 67 members of the 435-member House of Representatives — joined by but 14 members of the Senate — to vote no on the Defense of Marriage Act. Lewis didn’t take the route of arguing that the punitive measure was unnecessary given that no jurisdiction in the US had marriage equality. Instead, he made a full-throated case for the rights of same-sex couples to wed.

As Buzzfeed noted, in his remarks on the floor, he argued, “This bill is a slap in the face of the Declaration of Independence. It denies gay men and women the right to liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Marriage is a basic human right.”

Later, he would explicitly link the struggle for LGBTQ equality to the Black Civil Rights Movement he had joined in the late 1950s as a teenager.

“I have fought too hard and too long against discrimination based on race and color not to stand up against discrimination based on sexual orientation,” he argued. “I’ve heard the reasons for opposing civil marriage for same-sex couples. Cut through the distractions, and they stink of the same fear, hatred, and intolerance I have known in racism and in bigotry.”

It was no surprise, then, that Lewis proudly associated himself with all of the top LGBTQ legislative priorities that followed. Among them was the Equality Act — first introduced in 2015 — that would extend the protections of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and subsequent similar legislation to Americans on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. In the early discussion about the Equality Act, there was some vague talk that African-American leaders might be hesitant about any approach that tinkered with the cornerstone legislation of the Civil Rights Movement. The support of prominent Black members of Congress like Lewis put that worry to rest, and the support of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights is likely the most powerful tool in the arsenal of Equality Act advocates.

But to characterize Lewis merely as “progressive” or “ahead of his time” on LGBTQ issues is to miss a crucial point about his political philosophy, his compassion, and his decency as a human being.

John Lewis saw politics and social change from an intersectional perspective long before that terminology ever existed. He saw through the specifics of any given human rights question and understood the ignorance, hatred, and evil at the core of opposition to it.

Lewis was one of 10 children born to sharecropper parents in rural Alabama in 1940. He learned about Martin Luther King, Jr., and Rosa Parks by listening to them on the radio. By the time he was 18, he had met both.

As a student at a Nashville theological seminary, he joined other students in sit-ins at segregated lunch counters, where he discovered the importance of “good trouble, necessary trouble.” In 1961, he was one of the original 13 Freedom Riders pushing to integrate interstate bus travel. For his activism, he was beaten and jailed. Two years later, he became chair of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, a group whose militant but peaceful resistance to segregation makes it a forerunner of the Black Lives Matter Movement.

By that year, 1963, he had also become a close confidant of King, and he was the youngest of the speakers at the March on Washington. Since his death, stories have surfaced that Kennedy administration officials were on hand on the stage that day ready to pull the plug on Lewis’ remarks should they become too radical. Whether that’s true or not, it doesn’t seem that threat did much to persuade him to pull his punches.

“To those who have said, ‘Be patient and wait,’ we have long said that we cannot be patient,” he told the throngs on the Washington Mall. “We do not want our freedom gradually, but we want to be free now! We are tired. We are tired of being beaten by policemen. We are tired of seeing our people locked up in jail over and over again. And then you holler, ‘Be patient.’ How long can we be patient? We want our freedom and we want it now. We do not want to go to jail. But we will go to jail if this is the price we must pay for love, brotherhood, and true peace.”

He added, “If we do not get meaningful legislation out of this Congress, the time will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington. We will march through the South; through the streets of Jackson, through the streets of Danville, through the streets of Cambridge, through the streets of Birmingham.”

During his final days, Lewis several times took pains to salute the spirit of anger and rebellion that has filled America’s streets since the Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd.

On June 7, he joined Washington Mayor Muriel Bowser to visit the street mural of bright yellow paint reading “Black Lives Matter” in a two-block area leading to the White House. Afterward, in a statement referring to the 1955 lynching of a 14-year-old Black Chicagoan Emmett Till in Mississippi after charges of having offended a white woman, Lewis wrote, “Despite real progress, I can’t help but think of young Emmett today as I watch video after video after video of unarmed Black Americans being killed, and falsely accused. My heart breaks for these men and women, their families, and the country that let them down — again.”

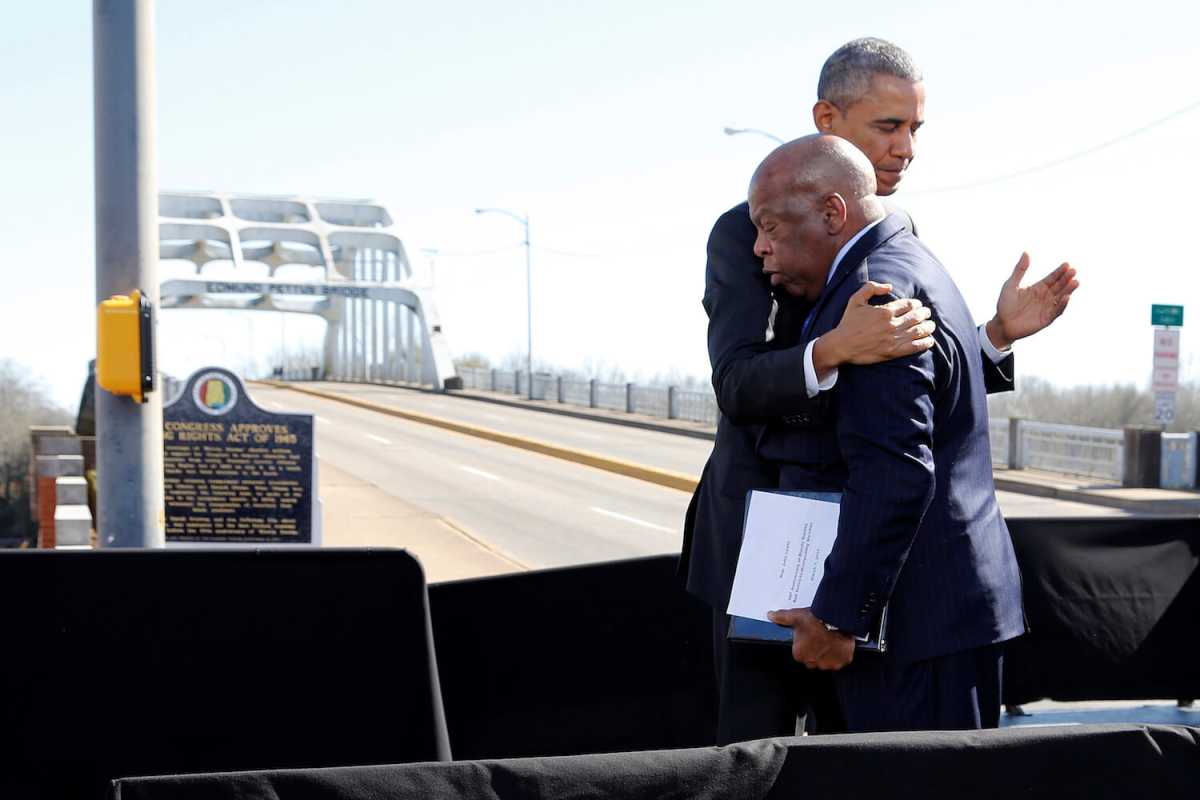

Nine days later, Lewis joined former President Barack Obama on a Zoom call that included an intergenerational group of African-American activists.

During the discussion, Lewis said, “We need to tell people, tell each other to be hopeful, to be optimistic and to never ever give up or to get down. I tell you the past few days been so inspiring to me. To see so many young people, so many children… it gives me great hope and we’re going to get there. It’s all going to work out. But we must help it work out. We must continue to be bold, brave, courageous, push and pull, ‘til we redeem the soul of America and move closer to a community at peace with itself.”