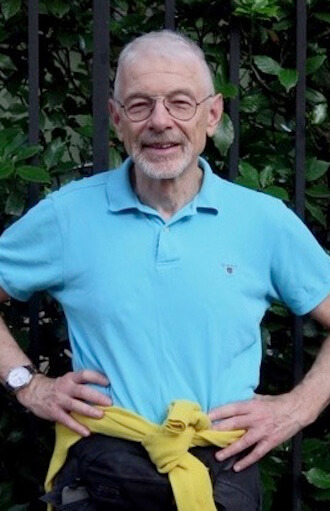

Perry Brass, one year after the removal of his prostate because of cancer, writes about what has gone well and what continues to create stress and risks. | RICARDO LIMON

This month marks a year since Dr. Ash Tewari performed a robotic-assisted, laparoscopic, radical prostatectomy — known as a RALP — on me at Mt. Sinai Hospital uptown. For the first several months after having my prostate removed, I was living in this almost euphoric fool’s paradise believing that I had returned to home base, cancer-free and back to normal — that is if normal consists of no longer having this small, strange, temperamental organ with all the nerves that route through it and that, to a great degree, controls urination and sexual response.

I was very lucky in many ways: Tewari did a great job with the operation itself, and sexually I was doing well, much better than many men in my circumstances who after a radical prostatectomy have found themselves with erectile dysfunction that does not respond to the usual medications — Cialis or Viagra. For them, another method is necessary — either injecting a form of prostaglandin directly into their penis, instantly dilating the penile arteries (a kind of “express” erectile enhancer), or using Alprostadil (brand name, Muse), a newer delivery format of prostaglandin that involves inserting a thin plastic tube directly into the urethra, popping the drug in that way.

I started going back to the Gay Men’s Prostate Cancer Support Group at Mt. Sinai at Union Square, supported by MaleCare (a nationwide advocacy and support group), and just hearing about these methods made me shudder.

Gay man’s 12-month roller-coaster ride after cancer prompted his prostate removal

Six weeks after my operation I had my first follow-up PSA reading, a blood test that tracks a prostate-specific antigen in your blood stream, marking infections and inflammations there. Ideally, my PSA should have been 0.00 — that is, no PSA reading in my blood. Ideally, however, doesn’t usually happen. My first reading came back 0.04; six weeks later it was 0.05. I was happy with both of these. If it was rising — and it’s possible for it to be rising simply because of some isolated cells infected with inflammation from the operation itself — it was in small increments.

As good as my sexual situation was, though, urination was a disaster. The first month after the operation, I had no control of it at all. I was using as many as nine “pads” (adult incontinence items like disposable briefs) a day. I could never be more than a few yards from a bathroom, although I discovered that there were worse things than producing some tiny leakage if your pad filled up. It was still warm enough for me to wear shorts, which made it easy to change pads.

I also noticed that sometimes the leaking and urgency were simply nerves: I could hold it in, if I had to, but I became scared of doing that. My worst fear was that, at some point, urine would just start pouring out of me, leaving a humiliating yellow trail behind.

In mid-September I had a consult with Dr. Avinash Reddy, Tewari’s consulting physician. I had been complaining about the leaking, and he decided to do a cystoscopy — a test using a camera inside a thin plastic tubing placed up your urethra that can view inside your bladder. Often a cystoscopy can detect infection or other problems. I had been dreading this, because my previous urologist, Dr. Craig Nobert, had done one on me after my trans urethral resectioning of the prostate operation (TURP) two years earlier, and it hurt like screaming hell. I was tense as piano wire when Reddy started it, and I apologized for being so nervous.

“Don’t worry,” he said. “I’ve never had this done. But if it were done on me, I’d be terrified.”

That helped. It actually did not hurt nearly as much, and it was very useful. Reddy brought his report to Tewari, and they decided that another approach was needed. The fact was, I was leaking and peeing so much because my bladder could not fully empty due to a constricted urethra.

Reddy explained what I needed: a dilation of my urethra.

“It’s a quick, one-day operation, no over-night, but you’ll have to wear a catheter for eight days afterward,” he said.

I was not happy about that, after having gone through sheer misery with a catheter for almost two weeks after my prostatectomy. But something had to be done. I was no longer sleeping, what with getting up seven times a night to pee.

The dilation was scheduled for two weeks later, at three in the afternoon, again at Mt Sinai uptown. I was in great spirits though hungry because, since it involves anesthesia, the procedure has to be done on an empty stomach. I arrived at 1 p.m., as told, got through intake instantly, went through pre-surgery counseling, and finally was sent to wait, in a hospital gown, in a small room by myself. At 3 p.m. nothing happened. Finally, I was informed there’d been a delay — no operating room was available. The delay stretched on for hours, and I felt like a stranded passenger at JFK whose flight could not take off. I was moved up to the surgery floor where I waited another hour. Finally, at 6, I was led into the operating room. Everyone was tired, I could tell. I was their last procedure of the day.

The operation was short — about 45 minutes — and I was unconscious for it. It’s an old procedure and has been done for hundreds of years. Basically, several stainless steel rods are pushed up your urethra to open it — simple as that. In the past, before anesthesia, it was done using bamboo rods, the thought of which made me flinch. I woke up in a recovery area and was quickly wheeled downstairs to a release area, where a nurse came to inspect me. The catheter was back in me, and she quickly told me how to empty the bag and change it. I was lucky; I’d already had experience with one, and at home I’d kept all the needed equipment and supplies.

Back at home, it seemed like “déjà vu all over again.” Here I was, recovering from yet another operation involving my… peepee. I’d had three now in two years. On my own, I experimented dealing with the catheter. Most men intuitively go for the loosest underwear they can get away with while wearing one, but I realized that’s why it hurts so much. It’s the friction caused by your anatomy swinging around there with a plastic tube up it. I started wearing my regular white cotton briefs, which kept the plastic tubing firmly in place inside me. That way, I found enough relief that I could exercise and move without problems, so the eight days weren’t horrible.

Getting it off, though, was not easy. For some reason, the small balloon that held the catheter in place would not deflate. Tewari’s P.A. Anthony tried it several times. I started to freak out, but he assured me that eventually it would come down. It finally did, and I could urinate again, easily, without it.

It took about a month for the dilation to kick in, then it did and I went back to being able to sleep and pee normally. I was also doing pelvic rehab, a procedure often prescribed for men coming out of a prostatectomy. Basically, a stainless steel probe that can be programmed to increasing levels of vibration is stuck up your butt, so that it can stimulate the muscles in your groin area, increasing their strength. Or, as Anthony called them, “kegels on steroids.”

Pelvic rehab is very intimate: it’s like having a vibrating dildo up you, except that it feels more like a battalion of ants, at first slowly crawling up your ass, then marching faster and faster until they’re doing a full-blast run. The degree of stimulation starts at 1 and goes to 80. I could get up to about 57 my first time with it, then it became unbearable. Dr. Steven Kaplan, my “pee doctor,” as I called him, signed me up for a round of four of them, once a week.

I noticed that pelvic rehab was always done by a female tech or clinician. I wondered if most straight men felt too uncomfortable having a man sticking a vibrating probe up them. At my gay men’s support group we talked about this — that it’s done so “clinically” with almost no connection between the patient and the clinician. One of the men had it done in New Jersey by a male clinician who was more supportive, more personal.

“He also understands the male anatomy is not like the female one,” my support group mate said. “We react differently.”

I was starting to sense that gay men are changing urology — we are more open about our feelings and our bodies. Also, more out gay men are going into the field. It was once so homophobically closed down that most gay medical students were scared of it — after all, you are in contact with men and their sexual organs in this specialty. But this is changing, and men in my group talked frankly about the gay urologists and clinicians they went to.

Alicia, the young woman who put me through my first month of pelvic rehab, hardly spoke. She would come into the room without asking how I was or if the treatment were actually working.

I asked her once why she did this.

“I know everything that’s going on from the data on the computer,” she replied. “I send a report to Dr. Kaplan, so I don’t need to ask you anything.”

I did not improve that quickly, so Kaplan signed me up for a second month. By this time, I was doing kegel exercises seriously at home, the dilation did kick in, my sexual response was fine, and urinary problems were diminishing. In early December, I went for another PSA. On my next visit, after pelvic rehab, Anthony asked to speak with me alone. My PSA had made a dramatic climb: to 0.11.

“This is still low — we don’t really pay attention to it until you hit 2.0,” he explained. “But we’ll monitor you more.”

In January, it went up to 0.13. I was starting to get anxious. Hugh, my husband, who’s a retired doctor, told me, “Don’t worry. It’s only a number, and it’s still very low.”

In March, it went up to 0.18. Anthony told me that in three months, they’d do another. I was crying when I left Tewari’s office. It was like I had not left the trenches of the cancer war, although as a soldier in it I’d still not experienced anything close to the combat so many other men I’ve met had. That was what scared me — what could be up ahead?

This June 8, I had blood drawn again. The result: 0.291. Now I was anxious. I felt I was clearly back in the trenches, as I faced another consult with Tewari.

I saw him the next Friday. He was with a new young P.A., Kacie, who was cheerful and made me feel better, not quite so anxious. Tewari was very consoling; we discussed my rising PSA.

“We need to find out what’s really going on, the cause of it,” he said.

He ordered three tests: another MRI, a PET scan, and another cystoscopy, which Reddy would do again in two weeks. He also suggested I take Zyflamend, an anti-inflammatory medicine. Cancer is generally considered to be a form of inflammation, so anything that reduces inflammation is good. I’d been on an anti-inflammatory diet — no sugar, no red meat — for three months. Tewari suggested I stay on it and assured me that I was making great progress — which is true, at least as far as my urination was concerned. But I needed to convince myself of that, also.

I had dinner with my friend Ricardo Limon that night. I told him how anxious I was.

Ricardo, who has a background in Buddhism, said, “You need to embrace this and claim it. Don’t hate it and try to separate from it. That will only cause suffering. But if you can embrace the cancer and everything that goes with it, you can overcome a lot of the fear. Not all of it — we all get afraid — but a lot of it.”

I am trying to do that now. It is strange being in this stage of prostate cancer: that I am both healthy and yet still have cancer. And that as much as I wanted it to leave, this persistent invader in the Pleasure Dome has still left some of its calling card within me.

Read Perry Brass' three-part story about going through his prostatectomy last year, here, here, and here.

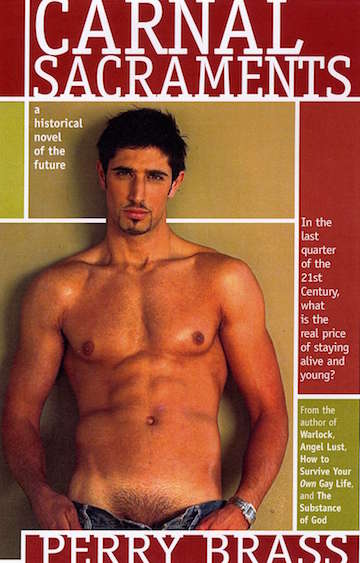

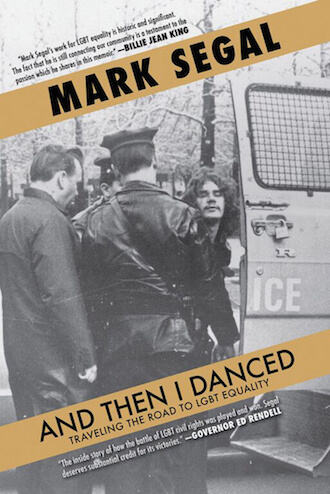

An award-winning writer and gender rights pioneer, Brass has published 19 books, including poetry, novels, short fiction, science fiction, and bestselling advice books (“How to Survive Your Own Gay Life,” “The Manly Art of Seduction,” “The Manly Pursuit of Desire and Love”). A member of New York’s Gay Liberation Front, in 1972, with two friends, he co-founded the Gay Men’s Health Project Clinic, the first clinic specifically for gay men on the East Coast, still operating as the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center. Brass’ work, based in a core involvement with human values and equality, encompasses sexual freedom, personal authenticity, LGBTQ health, and a visionary attitude toward all human sexuality. He is currently working on a memoir, set in 1965, when he was a 17-year-old gay kid living on the streets of Los Angeles and San Francisco.